About

Seeing a great piece of art can take you from one place to another—it can enhance daily life, reflect our times and, in that sense, change the way you think and are.

—Rachel Whiteread

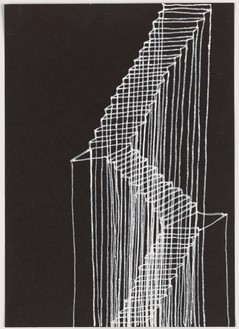

In Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures and drawings, everyday settings, objects, and surfaces are transformed into ghostly replicas that are eerily familiar. Through casting, she frees her subject matter—from beds, tables, and boxes to water towers and entire houses—from practical use, suggesting a new permanence, imbued with memory.

During her childhood in London, Whiteread’s parents’ interests in art and architecture made an enormous impact on her understanding of form and material. Her father’s fascination with urban architecture “enabled [her] to look up,” and her mother’s artistic practice allowed her to see the intersection of home and studio, life and art. Whiteread fondly remembers helping her father lay a concrete floor in their basement to convert it into a studio. The processes of looking, emptying, and filling run throughout her work, revealing how the surfaces of daily life can disappear and reappear, bearing the traces of their previous lives.

Whiteread studied painting at Brighton Polytechnic and sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Art in the 1980s. In 1988 she had her first solo exhibition, at the Carlisle Gallery in London, which included the sculptures Shallow Breath (1988), cast from the underside of a divan, and Torso (1988), the first in a series of cast hot water bottles. The Torso sculptures (1988–) are notably the only works in her oeuvre that make direct anthropomorphic reference. This exhibition marked the beginning of Whiteread’s use of domestic items; in these early pieces, she often left remnants of the original objects—such as scraps of wood—embedded into the cast forms.

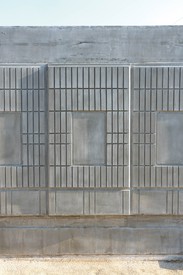

Ghost (1990) was Whiteread’s first large-scale sculpture and set in motion the ambitious, architecturally scaled works for which she is widely recognized today. Made by filling a room of a Victorian house in North London with concrete to create a solid cast that picks up the details of the walls, mantle, and windows, Ghost is a positive room-sized object that reveals itself gradually, as one encircles the huge form. Whiteread expanded on this working method in House (1993; destroyed 1994), cast from an entire Victorian terrace house. Whiteread created this work after all the other terraces in the row had been demolished, and it stood alone as a reminder of the working-class homes that once spanned the street. The sculpture sparked heated debates around issues of real estate, class divisions, and urban sprawl.

Whiteread’s first public commission in New York, Water Tower (1998), was cast from one of the city’s distinctive rooftop water towers in clear resin. “On a cloudy, gray day,” Whiteread explained, “it might just completely disappear. And on a really bright blue-sky day, it will ignite.” This ethereal presence contrasts with the weight of her Holocaust Memorial (2000), permanently installed in Vienna. Dedicated to the 65,000 Austrian Jews murdered during the Holocaust, the sculpture resembles, in the words of James Lawrence, “a private library turned inside out,” each wall lined with rows of nameless books, with two permanently closed doors on the front. In 2018 Whiteread’s US Embassy (Flat pack house) (2013–15) was unveiled at the United States Embassy in London, where the cast sections of an average 1950s suburban American house, arranged as separate geometric planes on a wall, greet visitors as they enter through the consular court.

Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

#RachelWhiteread

Exhibitions

Rachel Whiteread: … And the Animals Were Sold

An installation by Rachel Whiteread in the Palazzo della Ragione, Bergamo, Italy, commissioned by Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo and cocurated by Lorenzo Giusti and Sara Fumagalli, opened in June of 2023 and ran into the fall. Conceived in relation to the city, the architecture of the site, and the history of the region, it comprised sixty sculptures made with local types of stone. Fumagalli writes on the exhibition and architect Luca Cipelletti speaks with Whiteread.

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Winter 2022

The Winter 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Anna Weyant’s Two Eileens (2022) on its cover.

Rachel Whiteread: Shy Sculpture

On the occasion of the unveiling of her latest Shy Sculpture, in Kunisaki, Japan, Rachel Whiteread joined curator and art historian Fumio Nanjo for a conversation about this ongoing series.They address the origins of these sculptures and the details of each project.

Augurs of Spring

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

In Conversation

Tom Eccles and Kiki Smith on Rachel Whiteread

On the occasion of Artist Spotlight: Rachel Whiteread, curator Tom Eccles and artist Kiki Smith speak about the work of Rachel Whiteread through the lens of their personal friendships with her. They discuss her public projects from the early 1990s to the present, the relationship between drawing and sculpture in her practice, and the way her works reveal the memories embedded in familiar everyday objects.

In Conversation

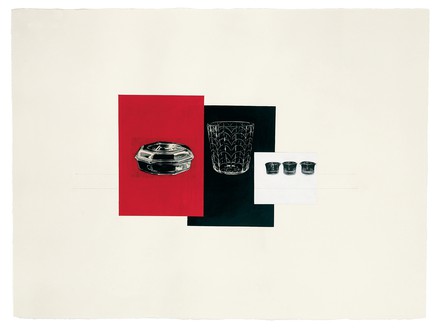

Rachel Whiteread and Ann Gallagher

Rachel Whiteread speaks to Ann Gallagher about a new group of resin sculptures for an exhibition at Gagosian in London. They discuss the works’ emphasis on surface texture, light, and reflection.

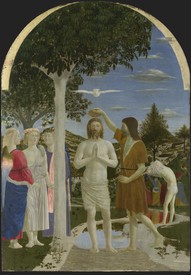

Rachel Whiteread on Piero della Francesca

Rachel Whiteread writes about the Italian artist’s Baptism of Christ (after 1437) and what has drawn her to this painting, from her first experience of it at a young age to the present day.

Cast of Characters

James Lawrence explores how contemporary artists have grappled with the subject of the library.

Shy Sculpture: Nissen Hut

Rachel Whiteread’s public sculpture Nissen Hut was unveiled in October 2018 in Yorkshire’s Dalby Forest. Curator Tamsin Dillon explores the dynamic history of these structures and provides a firsthand account of the steps leading up to the work’s premiere.

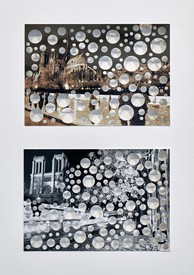

For Notre-Dame

An exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, is raising funds to aid in the reconstruction of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris following the devastating fire of April 2019. Gagosian directors Serena Cattaneo Adorno and Jean-Olivier Després spoke to Jennifer Knox White about the generous response of artists and others, and what the restoration of this iconic structure means across the world.

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2019

The Summer 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Afrylic by Ellen Gallagher on its cover.

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Spring 2019

The Spring 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Red Pot with Lute Player #2 by Jonas Wood on its cover.

Fairs, Events & Announcements

In Conversation

Rachel Whiteread

Tim Marlow

Wednesday, January 24, 2024, 7:30pm

Sarabande Foundation, London

sarabandefoundation.org

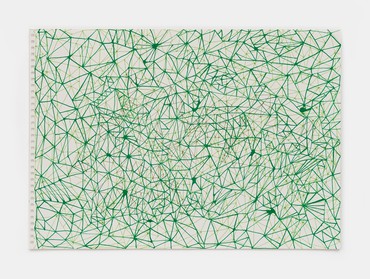

Rachel Whiteread will be in conversation with Tim Marlow, director of the Design Museum, London, for the next installment in the series of INSPIRED talks organized by the Sarabande Foundation. The pair will discuss Whiteread’s recent and current projects and delve into the twists and turns of her creative career to date—from concept to form, and everything in between. Using industrial materials such as plaster, concrete, resin, rubber, and metal to cast everyday objects and architectural elements, Whiteread’s sculptural works are instantly recognizable as evocative interrogations of negative space, from the domestic to the monumental.

This event was originally scheduled for Wednesday, December 6, 2023.

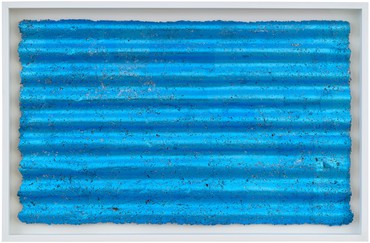

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Azure Blue), 2021–22 © Rachel Whiteread. Photo: Thomas Lannes

Visit

Rachel Whiteread

The Connaught Christmas Tree

November 16, 2023–January 7, 2024

The Connaught, London

www.the-connaught.co.uk

Encouraging passersby to celebrate a feeling of togetherness, Rachel Whiteread has used 102 white neon hoops to decorate the Connaught hotel’s 31-foot (9.4-meter) Nordmann’s fir. Whiteread regularly uses circular motifs within her practice and here they illuminate the streets of Mayfair, acting as a symbol of hope and unity this festive season.

Rachel Whiteread’s 2023 Connaught Christmas tree, London. Artwork © Rachel Whiteread

In Conversation

Rachel Whiteread

Briony Fer

Thursday, October 12, 2023, 3pm

Regent’s Park, London

www.frieze.com

Rachel Whiteread and Briony Fer will be in conversation as part of Frieze Masters Talks, a program that explores the connections between historical art and contemporary practice. The pair will discuss Whiteread’s recent and current projects, including . . . And the Animals Were Sold (2023), a new site-specific installation at the Palazzo della Ragione in Bergamo, Italy, which was conceived in relation to the historic architecture of the site and region. They will also discuss pivotal milestones in Whiteread’s life and career that paved the way for her to rise as a leading British artist. The event is free to attend with fair admission on a first-come, first-served basis.

Left: Rachel Whiteread. Right: Briony Fer

Museum Exhibitions

Closed

Rachel Whiteread

. . . And the Animals Were Sold

June 23–October 29, 2023

Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, Italy

www.gamec.it

. . . And the Animals Were Sold is a new installation by Rachel Whiteread in Bergamo’s Palazzo della Ragione that was commissioned by Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, Italy. Conceived in relation to the city, the architecture of the site, and the history of the region, it comprises sixty sculptures whose forms correspond to the empty space between the legs of two different chair models. Produced with local types of stone, the works suggest human absence and presence at once. Their arrangement evokes both the social distancing of the pandemic, which was particularly difficult for the Bergamo community, and the renewed proximity that is now possible.

Installation view, Rachel Whiteread: . . . And the Animals Were Sold, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, Italy, June 23–October 29, 2023. Artwork © Rachel Whiteread. Photo: Lorenzo Palmieri

Closed

Photography’s Last Century

The Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection

February 17–May 21, 2023

Jepson Center, Telfair Museums, Savannah, Georgia

www.telfair.org

Photography’s Last Century celebrates the remarkable ascendancy of photography during the past hundred years, and Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee’s promised gift of over sixty photographs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where this exhibition originated. The collection is particularly notable for its breadth and depth of works by women artists, its sustained interest in the nude, and its focus on artists’ beginnings. Work by Gregory Crewdson, Andreas Gursky, Man Ray, Andy Warhol, and Rachel Whiteread is included.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, 2005 © Gregory Crewdson

Closed

Jubiläumsausstellung—Special Guest Duane Hanson

October 30, 2022–January 8, 2023

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

www.fondationbeyeler.ch

This exhibition, whose title translates to Anniversary Exhibition—Special Guest Duane Hanson, features more than one hundred works from the foundation’s collection, from modern to contemporary art, to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the institution. Several hyperrealist sculptures by Duane Hanson enrich the presentation, opening up surprising perspectives on the exhibited artworks, architecture, staff, and visitors. Work by Francis Bacon, Georg Baselitz, Alberto Giacometti, Anselm Kiefer, Roy Lichtenstein, Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, and Rachel Whiteread is included.

Installation view, Jubiläumsausstellung—Special Guest Duane Hanson, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland, October 30, 2022–January 8, 2023. Artwork, front to back: © 2022 Estate of Duane Hanson/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Closed

Rachel Whiteread in

Deep Time: Commissions for the Lake District Coast–Landmark Artwork Proposal Exhibition

September 10–October 9, 2022

Beacon Museum, Whitehaven, England

thebeacon-whitehaven.co.uk

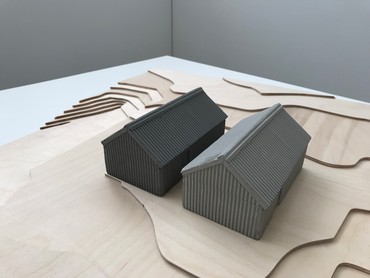

This exhibition showcases proposals developed over the last two years in response to the varied landscapes and coastline of West Cumbria, where the Lake District National Park meets the Irish Sea. Organized as part of the public art program Deep Time: Commissions for the Lake District Coast, the show presents designs, models, and films by four artists, including Rachel Whiteread, who have been shortlisted to produce a new landmark artwork for the borough of Copeland.

Rachel Whiteread, Drigg Hut, 2022 © Rachel Whiteread