Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

Whether or not the overlap was planned, the exhibitions Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of the 1930s, at the Neue Galerie, New York, and Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55, at the Harvard Art Museums’ Busch-Reisinger Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, coincided for about three months and complemented one another in stimulating ways. Before the Fall included international names from Germany’s prewar period such as Max Beckmann, Oskar Kokoschka, Max Ernst, and Otto Dix; similarly, Inventur represented most of the crucial figures of postwar German abstract painting—Willi Baumeister, Rupprecht Geiger, K. O. Götz, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Bernard Schultze, Emil Schumacher, Hann Trier, Heinz Trökes, Theodor Werner, Fritz Winter, and others—along with the abstract sculptors Karl Hartung, Hans Uhlmann, and Norbert Kricke. Some of the artists in this second group were also represented by earlier, figurative work, made in the last years of the war or shortly afterward, when they were turning to sources in prewar avant-garde movements such as Expressionism and Surrealism, before the increasingly international language of tachism or nonformal art became de rigueur in West Germany.

In each show, it was the forgotten or simply unknown artists who, taken as a whole, demonstrated the most surprising diversity of stylistic and psychological reactions to the imminent catastrophe and its grim aftermath. This was particularly the case with Inventur, which included a wide range of abstract or nonobjective work, some of it created by members of utopian groups (zen 49, Gruppe 53, and others), some by relatively isolated figures such as Hermann Glöckner, who was unable to exhibit or sell his sculptures during the Third Reich years and chose to remain in Communist East Germany after the war. Inventur featured artworks made out of poor, discarded materials—which postwar artists used as much from necessity as choice, faced by dire shortages and an all-pervading environment of rubble, especially in the bombed cities—and also, by contrast, a section on the sleek modernist design that emerged once the “economic miracle” of the 1950s was under way, demonstrating an idealistic belief in a renewed relationship between art and industry.

Unlike Inventur, Before the Fall covered Austria as well as Germany. At the entrance to the exhibition, large blown-up photographs of Adolf Hitler addressing ecstatic crowds in Vienna shortly after the Anschluss, in 1938, reminded visitors that the Führer himself was originally Austrian (he renounced Austrian citizenship in 1925). In entering Vienna, he was in a sense coming home to the city where he had spent his formative years: turned down for a place at the city’s Akademie der bildenden Künste, he had imbibed the anti-Semitism of Mayor Karl Lueger and his Christian Social Party. A frustrated artist, Hitler would surely have derived satisfaction from the fact that once Austria had been incorporated into the Reich, Vienna became a stop on the tour of the Nazis’ 1937 exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate art). As an introductory panel in Inventur pointed out, only about a quarter of the more than 100 German artists included in Entartete Kunst fled Nazi Germany or Austria, with the remainder opting for various forms of what after the war came to be called Innere Emigration (inner emigration). Both shows’ curators, Olaf Peters (Before the Fall) and Lynette Roth (Inventur), emphasize in their respective catalogues that this was a contested term with no accepted definition; it meant something different in each individual case.

Before the Fall movingly made clear which artists did not survive, dying in battle or bombing raids or, like Friedl Dicker-Brandeis and Felix Nussbaum, being persecuted and murdered by the Nazis. An Austrian, Dicker was one of the students of Johannes Itten who followed him from Vienna to the Bauhaus. In the early 1930s, having returned to Vienna, Dicker taught art in kindergartens, joined the Communist Party, and produced sociopolitical photocollages, often focusing on child welfare. Arrested and interrogated, she emigrated to Prague in 1934 and later married Pavel Brandeis. In 1942 they were apprehended and sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, where she took it upon herself to encourage children to draw as a means of preserving a modicum of dignity and calm in the face of their impending fate. In 1944 she was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, but not before hiding thousands of drawings by her young charges, which were found after the war. Dicker’s oil painting Verhör II (The Interrogation II, 1934–38), based on her own experience at the hands of the Austrofascists, is a terrifying image of blindness and pulverized flesh that anticipates the anonymous pulped heads of Nazi victims evoked so shockingly in Jean Fautrier’s Hostage series a decade later.

In Nussbaum’s Selbstbildnis im Lager (Self-Portrait in the Camp, 1940) the artist eyes us warily, gaunt and unshaven, while in the background one fellow inmate defecates into a dustbin and another, seminaked, searches the prison yard for scraps. The painting, which is in the Neue Galerie’s permanent collection, was one of several arresting realist works in the show. Nussbaum was interned by the French in 1940 as a German “enemy alien,” despite being a Jew in flight from Germany. Deported back there, he succeeded in escaping and for the next four years lived a life on the run or in hiding. In 1944 the Nazis caught up with him and, like Dicker, he was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and gassed.

The artists represented in Inventur survived the war, but while they hadn’t been hunted down and killed, a significant number had been ostracized by the Nazi regime, forbidden to exhibit, teach, or sell, or even imprisoned. Others were bombed out of their homes and studios, losing all or most of their work. Of the men who were called up to fight, some returned home wounded while others ended up in a Russian or American POW camp. Women experienced evacuation to the country, or, worse, the Soviet occupation of Berlin. After such hardship and suffering it is remarkable that anyone had the will or strength to make art at all.

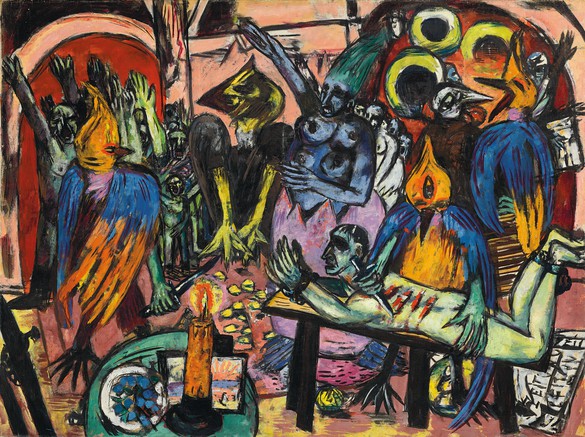

Rather than being organized chronologically, Before the Fall was divided into traditional genres such as portraiture (both individual and group), landscape, and still life, with separate sections on photography and works on paper. But that innocuous-sounding structure gives no hint of the anxiety or threat emanating from many of the images on show. Mythical birdlike creatures become metaphors for mass hysteria and sadistic violence in Beckmann’s Hölle der Vögel (Birds’ Hell, 1938), painted in exile in Amsterdam. An equally sinister spirit pervades those paintings by Ernst featuring monstrous animal hybrids and unnatural plant forms, such as Die Barbaren (Barbarians, 1937). Artists as different from one another as Hans Adolf Bühler, Karl Hubbuch, Richard Oelze, Franz Radziwill, Rudolf Schlichter, and Franz Sedlacek appear to have used landscape, whether dreamlike or apocalyptic, to denote various sorts of political allegory. Forest paintings, recalling the darkest aspects of German Romanticism or Grimms’ fairy tales, suggest that irrational fears were never far from the surface.

It would be dangerous, however, to read too much of a sense of foreboding into the hallucinatory intensity of Radziwill’s landscapes or the obsessive precisionism of Sedlacek’s gothic fantasies. Both artists were members of the Nazi party, although Radziwill (dubbed “Naziwill” by artist Karl Hofer after the war) later edited his oeuvre to make it seem as if he had been opposed to the regime. The Austrian Sedlacek, on the other hand, showed work in the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) in Munich in 1937, mounted simultaneously with Entartete Kunst in that city as a contrasting show of Nazi-approved art, and demonstrating, as Jonathan Petropoulos argues in his book Artists under Hitler, that a kind of soft modernism could fit under the rubric of such work. In 1945, as a fifty-four-year-old officer in the Wehrmacht, Sedlacek went missing, presumed dead, on the Russian front. Another Austrian, Rudolf Wacker, endured arguably a worse fate: an opponent of the Nazis, he was hauled before the Gestapo after the Anschluss and suffered a fatal heart attack under interrogation. His still lifes, which often include dolls or wooden busts as human surrogates, were among the most disturbing images in Before the Fall—examples of Neue Sachlichkeit at its most glacial and alienating.

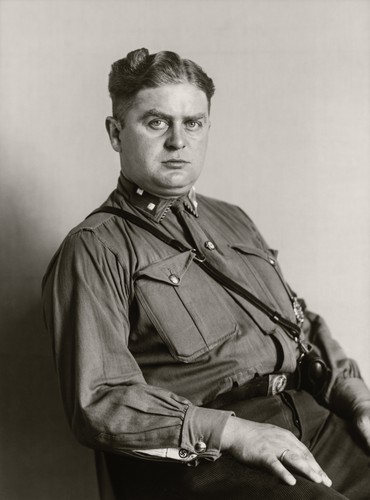

In the sections devoted to works on paper and photographs, it was exciting to see a group of satirical caricatures by Alfred Kubin from the 1930s, a period of his work that is less celebrated than the morbid, proto-Surrealist visions of his earlier symbolist phase: Max Klinger has yielded to Goya and Daumier as inspiration. Already fifty-six when Hitler “seized” power, Kubin seems to have been under no illusion about what was in store. The photographer Helmar Lerski is relatively little known today, but in Berlin in the 1920s he was an acclaimed cameraman on a number of Expressionist films, including Fritz Lang’s Metropolis; his manipulation of light and shadow in close-ups of the human face was particularly admired. In 1929 he became a full-time portrait photographer and in 1931 published a book called Köpfe des Alltags (Heads from everyday life), intended to reveal archetypal “truths” rather than individual physiognomies—a sort of abstract version of August Sander’s more famous decades-long Menschen des 20 Jahrhunderts (People of the Twentieth Century) project, portraits from which were also shown in Before the Fall. Lerski left Germany in 1933 for Palestine, so it was puzzling to find him represented in the exhibition by a later project, Verwandlungen durch Licht (Metamorphosis through Light, 1936), consisting of multiple images of a single face, even though he did regard it as his masterpiece.

The same question could have been asked about the appearance in the exhibition of Kokoschka’s allegorical portrait of the elderly Tomáš Masaryk, first president of Czechoslovakia, painted in Prague in 1935–36. Kokoschka, an outspoken critic of tyranny in all its forms, had left Austria in 1934, deeply concerned by the collapse of the country’s democratic government and rapid slide into authoritarianism. He alludes to Masaryk’s humane, democratic policies by showing him next to the figure of a mutual hero of the two men, the great seventeenth-century educational reformer Jan Amos Comenius. Since Masaryk stood for values antithetical to Nazi ideology, the inclusion of this magisterial portrait in the exhibition was fully justified. While sitting for Kokoschka, Masaryk helped him apply for Czech citizenship; this stood the artist in good stead a few years later in Britain, where he was classified as a “friendly alien” and thus not interned, as so many political refugees from Germany and Austria were in the panic of 1940.

Inventur contained over 160 works by nearly fifty artists, grouped under five main headings: “Modern Art in Nazi Germany,” “War’s End,” “Postwar Pluralism,” “Economic Recovery,” and “The 1950s.” Its powerful argument was that the artistic diversity of West Germany’s immediate postwar period has been overshadowed by a narrative that posited abstraction as the predominant style, usually in opposition to the propagandist Socialist Realism expected of artists in East Germany from the late 1940s onward. The show’s end date of 1955 was significant: this was the year of the first in the documenta exhibition series, in Kassel, West Germany, which promoted a theory of continuity between prewar and postwar cultural modernism. By the second documenta, four years later, a wall panel in Inventur reminded us, “postwar art had become synonymous with Western abstraction.”

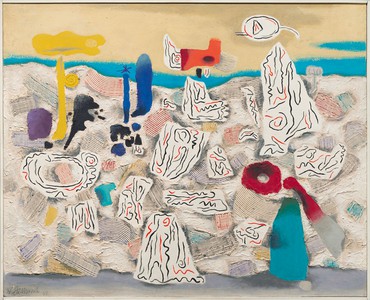

Fifty-six of the works exhibited in Inventur are in the Busch-Reisinger’s permanent collection, nineteen of them acquired in the last couple of years. The Busch-Reisinger also possesses earlier work by artists who featured prominently in the exhibition, such as Baumeister, whose Kopf (Head, 1920), in oil paint, pencil, and plaster relief, was on display elsewhere in the museum. That work shows that Baumeister’s interest in unusual combinations of materials predated his postwar experiments. Wachstum der Kristalle II (Growth of the Crystals II, 1947/52, also in the Busch-Reisinger collection and included in the exhibition), demonstrated to striking effect the combing technique that he used to pattern and color smears of putty with combs left over from his training as a decorative painter before World War I. In the early 1940s, Baumeister, together with Oskar Schlemmer and Franz Krause, were employed at a lacquer factory run by Dr. Kurt Herberts in Wuppertal, investigating the properties of new synthetic paints. Privately, they experimented with an “automatic” abstract language of mixed media, brushless application, and fluid color dripped onto small steel panels. These works would appear to have had important implications for artists such as Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter in the 1960s.

Inventur took its title from a 1945 poem by Günter Eich, written in an American prisoner-of-war camp, in which the poet poignantly lists his few worldly possessions, including his precious pencil and notebook, as if they were all that lay between him and an existential void. In her introductory essay to the show’s catalogue, Roth states that “after war’s end, most Germans avoided direct political engagement, instead turning with renewed vigor to the private sphere.” It didn’t take long, however, for what she calls “the ruinscape of the country’s major cities” to work its way into art, becoming a popular pictorial trope in the paintings of Werner Heldt, Erwin Spuler, Dix, Hofer, and others, as well as informing much of the photography and film of the period. However, in the entire exhibition only one work referred directly to the concentration camps: Carl Buchheister’s striking abstract assemblage of blood-red paint and found objects, Komposition mit brutalen Gegensätzen (Composition with Brutal Oppositions, 1949), and then only in its subtitle, KZ-Bild (Concentration Camp Picture). Otherwise, on the subject of the camps, silence prevailed, as if the Holocaust had never happened or was too enormous a crime for German artists to address. It would take another decade for it to surface, however obliquely, in the work of Joseph Beuys; another generation for it to haunt Anselm Kiefer’s landscapes of death.

1Jonathan Petropoulos, Artists under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), especially the chapter “Accommodation Realized,” pp. 177–91.

2Lynette Roth, “Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55,” in Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55, exh. cat. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Art Museums, 2018), p. 30.

3Ibid., p. 49.

Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of the 1930s, Neue Galerie, New York, March 8–May 28, 2018; Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts, February 9–June 3, 2018