Philippe Roger is a scholar and the editor of Critique, the journal founded by Georges Bataille in 1946. He has written extensively on history, literature, criticism, and the arts. He is a senior research fellow at France’s Centre national de la recherche scientifique and a professor at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, both in Paris.

From the late 1920s until his death, in 1962, Georges Bataille stood out as one of the most original figures in the French intellectual arena. A powerful yet elusive thinker, he crisscrossed many fields, from metaphysics to politics, from anthropology to aesthetics. To dedicate an exhibition to him—Critical Dictionary: In Homage to G. Bataille, at Gagosian Paris earlier this summer—is at the same time a beau geste and a bold gesture. Why should an art gallery pay “homage to G. Bataille”? Why the intriguing title “Critical Dictionary” (the phrase is borrowed from him)? Some may raise a quizzical eyebrow at seeing a tribute paid, through beauty, to a writer fascinated by foulness and the squalid. Others may question the relevance of placing art under the patronage of a philosopher who frowned on “works of art” as reified products, adamantly asserting the importance of the creative moment over the artistic artifact. This is what makes the Gagosian exhibition so unusual: a challenge, to be sure, it is also a visual and conceptual riddle for every viewer to solve.

As a matter of fact, art did not rank first among Bataille’s interests: sexuality, mysticism, “negative theology,” and a very personal brand of political anthropology took precedence. Crossing disciplinary boundaries was always at the core of his work. In 1937, he joined with Michel Leiris, a writer fascinated by anthropology, and Roger Caillois, a young grammar professor with a passion for social mythologies and the beauty of rocks, to launch the Collège de sociologie, an informal debating society where, for two years, some of the most agile minds in Paris convened to discuss fascism, religion, sacrifice, and the looming war.1 This is not to say that art was foreign to Bataille; far from it. A dissident Surrealist, he befriended artists such as André Masson and René Magritte. Nor was he indifferent, as an analyst of the collective psyche, to the momentous changes in the status of art that had occurred at the turn of the twentieth century, resulting in the emancipation of artists from socially preassigned aesthetic programs, whether religious or political, and paving the way for, in his word, artistic “autonomy.”

Bataille’s relationship to art, however, was always ambivalent. While demonstrating a vivid interest in painters from Goya and Manet2 to Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Klee, he wondered whether contemporary art had not reached an impasse, precisely because of the secularized individualism implicit in its newly autonomous status, and he often cast doubts on the ability of contemporary artists to innovate. “Nothing shockingly new has happened in painting since Dalí and Balthus,” Bataille wrote in 1956—a declaration that art historians are likely to find odd.3 Questionable as it is, the statement provides us with a precious clue: the key word here is not so much “new” as “shocking,” with its rich spectrum of semantic associations, ranging from surprise to mental or physical trauma. For Bataille, experiencing art is what really matters, and this experience necessarily involves violence. The French adjective in his assertion, “choquant,” can refer to various moral transgressions; most of the time, however, it connotes deviant sexual behavior. Mentioning the sexually explicit Salvador Dalí, along with the discreetly “perverse” Balthus, as the two last great providers of the “shockingly new” makes perfect sense within the framework of Bataille’s reading of art as an unexpected, destabilizing, potentially traumatic blow to the viewer’s consciousness and sensibility. In the wake of Stendhal’s famous definition of beauty as “nothing other than the promise of happiness” (and a definitely sensual, eroticized happiness, at that), Bataille associated art with Eros as lightning strokes—“fulgurations.”

For Bataille, experiencing art is what really matters, and this experience necessarily involves violence.

While eroticism as shock and awe was ever present in Bataille’s philosophical essays, it took center stage in his literary works. His most widely read book today is probably the notorious Histoire de l’œil (Story of the Eye), published (under a pseudonym) in 1928. So “graphic” were the tableaux vivants in L’Histoire de l’œil that it took another fifty years before the book could be translated into English!4 While the enucleated eye in the story takes on an explicit, crude sexual significance, it is also an apt metaphor, not only for our bewilderment but for the special kind of blindness required of us when facing or being confronted by art.5 Blinding ourselves to the plain and obvious is the first step toward a deeper vision of both art and life, revealed to us as part of an “inner experience,” a key phrase in Bataille’s idiom and the title of one of his philosophical essays.

One year after the publication of L’Histoire de l’œil, Bataille and his friends started writing entries for their Dictionnaire critique, their “Critical Dictionary.”6 Sharing little with the commonly received concept of a dictionary or an encyclopedia, the project instead drew its inspiration from the Surrealist taste for lexicalized pamphlets and, beyond Surrealism, from a long tradition of playful, ironical, polemical lexicons that thrived in eighteenth-century France, with Voltaire the recognized master of the genre.

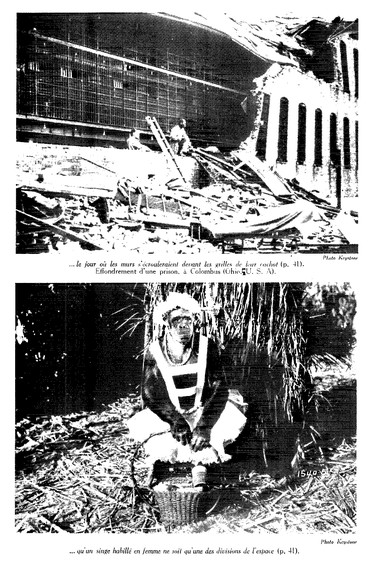

In its original format, the “Critical Dictionary” appeared not as a book but as entries randomly published in Documents, the short-lived but strikingly innovative journal that Bataille ran in 1929–30. In a thoughtful and provocative way, Documents combined text and pictures, philosophical musings and “newsreels” à la John Dos Passos. It was not “about” art: it was about artfully rethinking nature and society, in a way that was a shock to many, including its sponsors, who threw in the towel after only fifteen issues. Documents promoted tension between the visual “document” (first-rate photographers such as Jacques-André Boiffard and Éli Lotar contributed) and the written word, the poetic impact or polemical violence of the texts being multiplied by the beauty and strangeness of the images, and vice versa. The entries of the “Critical Dictionary” pushed this procedure to its limits. While pictures retained their traditional illustrative role in other sections of the journal, text and photographs clashed in these “chronicles” in a strident, brutal, and often indecipherable way. The entry for “space” (published in Documents no. 1, 1930), provides an example of the “shocking” strategy developed by Bataille: the first picture, showing the collapse of a jailhouse in Columbus, Ohio, allows an easy connection with the “topic”; but what about the second picture, of a “monkey dressed as a woman”?

Amazement, for Bataille, was the utmost symptom of artistic experience.

Bataille conceived of Documents as an arena for confrontation and destruction, an art gallery turned shooting gallery. Rather than providing the reader with definitions, his “Critical Dictionary” ruined the very notion of the definition as a semantic pillar of the social order. It was not supposed to promote “dialogues” between artists, on the one hand, and philosophers and writers, on the other; rather, it was designed to create clashes between words and words, words and pictures, art and the world. Rather than articulating a social critique, Bataille set out to disarticulate received social representations, thus exacerbating all forms of crisis (of art, of philosophy, of humanism, etc.). He wanted to turn words against (ideological) discourses and art against itself. Needless to say, this is not exactly what the French gallerist and collector Georges Wildenstein had in mind when he decided to fund Documents, and hired the thirty-three-year-old Bataille to run it. Many readers were appalled by the journal’s accumulation of “base” material, often verging on the monstrous. Wildenstein, however, along with the established art historians who contributed, may have been still more dismayed by Bataille’s unapologetic praise of the “formless.” How could an art magazine promote a concept so abhorrent to art lovers in the first half of the twentieth century? And how can an art exhibition today retain or revive the spirit of violent confrontation central to Bataille’s project, and reclaim his notion of the “formless” for its own purposes?

Let us first dispel a possible misunderstanding, taking hints from Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Georges Didi-Huberman. In their classic analyses of Bataille’s “formless” in connection with modern art, we find them in agreement on one central point: Bataille’s insistence on the “formless” implied no rejection of form(s) as such. In turning to the word informe, Krauss writes, Bataille wanted to “evoke a process of ‘deviance,’” “a de-classing in every sense of the term.”7 While denouncing the bourgeois cult of the “beautiful form,” he never ceased, especially in Documents, to combine forms, proposing new aesthetic configurations through unexpected encounters, thereby giving new contours to the world itself. In Documents, Didi-Huberman writes, the play between words and images is “insubordinate” but is never left to chance: it is “genuinely a work on forms.” Through “figurative montage,” Bataille coerced artistic forms into “contributing to their own transgression.”8 This is an apt description not only of Bataille’s “Critical Dictionary” but also of Critical Dictionary the exhibition, a “figurative montage” in its own right.

Let us enter a room, a fairly large one. Artworks are paired together, just as pictures were paired in Documents. In one corner, peaceful coexistence seems to prevail between Vasily Kandinsky’s Dicht and Magritte’s Démon de la perversité (The Imp of the Perverse). Not only are the two paintings united by their similar format and subdued colors, they are matched chronologically: both are dated 1929, the year Documents was founded. Nothing here to scare the art historian: contextualization mitigates confrontation. But lo! Look to the opposite corner. A huge white Louise Bourgeois sculpture with a central eye, Cleavage (1991), seems to deliberately ignore the three black, eyelike holes peering blindly at the viewer in Alberto Burri’s Rosso Plastica (Red plastic, 1968).9 Both the Bourgeois and the Burri pieces, however, seem to mutely answer the silent question asked by the three wood-colored orifices in the Magritte across the room. The reassurance provided by contextualization thus dissolves into discomfort, a feeling of uncanniness reinforced by the title of both the Magritte—The Imp of the Perverse, a reference to Edgar Allan Poe’s tale about a self-incriminating murderer—and the Bourgeois, Cleavage, which can refer to an eroticized part of the female body but also to a butcher’s cleaver, and more specifically to the famous cleaving of an eye performed in Luis Buñuel’s film Un chien andalou. (The epoch-making movie premiered in 1929, and Bataille, writing in Documents, described the episode of the eye split with a razor under the title “Cannibal treat.”) We will stop here and let the show reveal its further instances of conflicting closeness, such as Joe Bradley’s Real Goon (2017)—another menacingly titled work—lurking in a third corner of the same room behind a figure from Togo echoing the fascination with Africa characteristic of Documents.

In Documents, Bataille created “a stunning network of suggested relationships, of implicit or explosive contacts, of true or false resemblances, of false or true dissemblances.”10 So does this exhibition, in a less “shocking” but no less “amazing” way. Amazement, for Bataille, was the utmost symptom of artistic experience; a quarter century after Documents disappeared, he would describe the amazed first glance of the three schoolboys who discovered the cave paintings of Lascaux as the apex of aesthetic emotion.11 The ultimate (and logical) paradox of the Critical Dictionary exhibition is to multiply connections and accumulate complexity to achieve the very same goal: refreshing our gaze, allowing us to wonder at art anew.

1The society’s short-lived existence is remarkably documented in Denis Hollier, ed., The College of Sociology (1937–39), 1979, trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis: University of Minesota Press, 1988).

2Bataille’s Manet (Geneva: Skira, 1955) is his only monograph on a painter.

3Bataille, “L’impressionnisme,” Critique 104 (January 1956), pp. 3–13.

4Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye, trans. Joaquim Neugroschel (New York: Urizen Books, 1977). In 1953 an English translation was issued by Olympia Press in Paris, but under a different author name and title (Pierre Angelique, A Tale of Satisfied Desire) and with a limited print run; the translation was by Austryn Wainhouse.

5Blindness as the ultimate emancipation of the eyes is a frequent theme in Bataille’s writings on art. In “L’impressionnisme” he quotes Cézanne on Monet: “He is nothing but an eye, but what an eye!,” adding this comment: “All Monet is in his wish to have been born blind, and thus be just this organ in its purest state.” For another approach to blindness in connection with painting, see Jacques Derrida, Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins, exh. cat., Louvre, Paris, 1990, trans. P.-A. Brault and M. Naas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

6A new French edition of the Dictionnaire critique (including the illustrations) was published by Éditions Prairial, Paris, in 2016. An English version is available in G. Bataille, Isabelle Waldberg, and Iain White, Encyclopaedia Acephalica: Comprising the Critical Dictionary & Related Texts, Atlas Arkhive 3, 1996, available online at www.ferlandweb.com/encyclopaedia-acephalica-atlas-arkhive.pdf (accessed June 23, 2018).

7Rosalind E. Krauss, “The Destiny of the Informe,” in Yves-Alain Bois and Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997), p. 252. The book appeared in the wake of an exhibition curated by its co-authors at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris: L’Informe: mode d’emploi, May 21–August 26, 1996.

8Georges Didi-Huberman, La Ressemblance informe, ou le Gai Savoir visuel selon Georges Bataille (Paris: Macula, 1995), pp. 14, 21. My translation.

9Another work by Burri, Combustione Plastica (Plastic combustion, 1964), had been introduced by Bois and Krauss in their discussion of Bataille’s “base materialism.” Formless: A User’s Guide, pp. 29–31.

10Didi-Huberman, La Ressemblance informe, p. 13.

11Bataille, Lascaux; or, The Birth of Art: Prehistoric Painting, trans. Austryn Wainhouse (Lausanne: Skira, 1955). An insightful account of Bataille’s fascination with Lascaux appears in Daniel Fabre’s Bataille à Lascaux, subtitled “How prehistoric art appeared to children” (Paris: L’Échoppe, 2014).

Critical Dictionary: In Homage to G. Bataille, Gagosian, Paris, June 1–July 28, 2018