Sebastiano Barassi is Head of Collections and Exhibitions at the Henry Moore Foundation.

The observation of nature is part of an artist’s life, it enlarges his form-knowledge, keeps him fresh and from working only by formula, and feeds inspiration. The human figure is what interests me most deeply, but I have found principles of form and rhythm from the study of natural objects such as pebbles, rocks, bones, trees, plants etc. . . . There is in Nature a limitless variety of shapes and rhythms (and the telescope and microscope have enlarged the field) from which the sculptor can enlarge his form-knowledge experience.

—Henry Moore, 1934

Nature was always at the heart of Henry Moore’s artistic vision. Throughout his career his unique and innovative visual language was based on the reinterpretation of organic forms, be they the human body, an animal, a landscape, or objets trouvés such as seashells and bones. Moore traced this interest back to his childhood in Yorkshire, in particular to his fascination with places like Adel Rock or the slag heaps near coal mining villages, which he enjoyed both as landscapes and for their sculptural qualities. The observation of nature dovetailed in his practice with the use of natural materials, whether the native stones and wood of his early carvings or the found objects that inspired so much of his postwar work. Equally important in Moore’s thinking was the relationship of sculpture with the landscape, an idea which played a central role not only in the making but also in the display and reception of his art.

Moore thought of his work as animated by elements of intuition, surprise, asymmetry, softness, and biomorphism, characteristics which he associated with romantic art, and which he considered to be polar opposites to the classicist canon he had rejected as a young artist. Having developed artistically in a modernist milieu concerned primarily with formal invention, which had emerged in early-twentieth-century British art in response to the theories of “significant form” championed by the art critics Clive Bell and Roger Fry, Moore’s creative approach focused almost exclusively on formal investigations, and was generally divorced from narrative content—although this did not mean, he was always eager to clarify, that his work should ever be labeled “abstract.” The concentration on pure form helps to explain the relatively small number of subjects in Moore’s oeuvre. Among his favorite themes were the reclining figure and the mother and child, simple motifs which offered virtually endless opportunities for formal reinvention. The reclining figure, which in his work is almost exclusively female, allowed Moore to study the human body in a wide range of variations, simply by altering the arrangement of limbs or the orientation and incline of the head and torso. The mother and child motif allowed him to explore the juxtaposition and interaction between independent forms of different sizes.

The reclining figure . . . allowed Moore to study the human body in a wide range of variations, simply by altering the arrangement of limbs or the orientation and incline of the head and torso.

Early in his career Moore developed ideas for sculpture predominantly by drawing. From the late 1940s, as he started to move away from direct carving in stone and wood and towards modeling soft materials and casting in metal, he began to create new work in three dimensions, usually with small maquettes in plaster, clay, or wax. These had the great advantage of allowing him to hold a complete sculpture in his hand and study multiple views at once, helping him to visualize its realization in full size.

Moore frequently used a found natural object as the starting point for a maquette, either as inspiration, as a form to be cast in plaster and then reworked into a figure, or by building the model directly out from a flint or bone. This reliance on naturalia was, in some ways, an evolution of the principle of “truth to material” which had dominated Moore’s prewar carvings—dictating that the sculptor should always respect the physical and aesthetic properties of each material. In carving, the idea was to let the natural qualities of the block of stone or wood determine the final form of the sculpture. With the use of natural objects, Moore similarly let nature suggest ideas and drive their translation into sculptural forms.

In the early 1920s, as Moore’s interest in carving was expanding, Norfolk became the new home of several members of his family. His parents and sister Mary moved to Wighton in 1922, leaving behind the industrial pollution of Yorkshire for more salubrious climes; his sister Betty married a teacher and moved to Mulbarton, near Norwich; and his brother Raymond became the headmaster of a school in Stoke Ferry, near King’s Lynn. Moore was a student at the Royal College of Art in London at this time. While he followed the traditional curriculum during the week, at weekends he wanted to focus on more innovative work, predominately carving, which aligned him with the avant-garde sculptors he admired. Lacking an adequate studio space in London, he decided to work in the garden of the family home in Wighton. Although largely the result of practical necessities, it was thanks to this experience that he began to appreciate the value of working immersed in nature. He later stated that he found “a tremendous pleasure in actually working in the open air. To work shut inside a studio at times when the weather is good is like being in a prison.”1

In the late 1920s and 1930s Norfolk also became a frequent source for Moore’s growing collection of natural objects. He picked up stones and seashells from the coast which he took back to his London studio, occasionally making small carvings from pieces of ironstone he found on the local beaches. Moore described the collection, which also included animal bones and driftwood, as a “library of natural forms.”

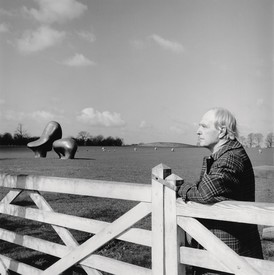

At the start of World War II Moore moved to Perry Green, the hamlet in the Hertfordshire countryside which became his home for the rest of his life. His house, Hoglands, and studio quickly filled up with hundreds of natural objects. This immersion in organic forms echoed that he found in the new rural surroundings, which played an increasingly central role in Moore’s creative vision. He came to believe that sculpture is first and foremost “an art of the open air; daylight — sunlight is necessary to it, and for me its best setting and complement is nature . . . Natural light (rather than studio lighting) makes the sculptor produce forms which are complete and real like the nature around him.”2

But it was not just the making of sculpture that Moore believed benefited from natural surroundings. He repeatedly declared his preference for showing work in the landscape, maintaining that the optimum setting consisted of long views against the open sky, or fields of grass with a few trees. This conviction played a big part in Moore’s move towards larger works in the 1960s, which was driven, among other considerations, by his awareness that when sculpture is placed in the open air it generally tends to look smaller than when it is seen indoors. For his larger works Moore frequently opted for more abstracted and geometrical forms, often inspired directly by natural objects, as is evident in the evolution of Spindle Piece (1968–69) from flint to monumental bronze, via a maquette and what Moore described as a “working model” (a median-size version). As Richard Calvocoressi points out, moving away from the life-size human figure allowed Moore to invent “forms that interlock, touch, point, twist, split . . . soar upwards . . . repeat themselves” and exploit the expressive power of a nonfigurative language.3 In Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae (1968) the forms, although organic as the title suggests, have been enlarged and reinterpreted to such an extent that they appear almost machine-like.

[Moore] repeatedly declared his preference for showing work in the landscape, maintaining that the optimum setting consisted of long views against the open sky, or fields of grass with a few trees.

At Perry Green, Moore was able to experiment with the siting of his work against a harmonious and constantly changing backdrop that shifted with the seasons. As he acquired more land at the back of Hoglands, he developed it specifically as an environment for sculpture, with subtle view changes through increasingly larger areas for works of different sizes. The availability of cheap land and farm buildings also allowed him to create dedicated studios for each medium. Over the years he set up separate spaces for carving, modeling, the enlargement and patination of sculpture, drawing and printmaking, as well as a number of storage buildings and huts. Less permanent structures like the “summer house”—a small drawing studio mounted on a turntable—and the “plastic studio” allowed Moore to work immersed in natural light and surrounded by views of the landscape.

From 1970, a new purpose-built maquette studio provided Moore with a space to think, work, and get away from the activities and distractions elsewhere on the estate. It soon became his favorite space to work on new ideas and immerse himself in his ever-growing collection of natural objects. Among these was an elephant skull, whose story is exemplary of how Moore drew inspiration from nature.

The elephant skull was given to Moore in 1968 by his friends Julian and Juliette Huxley, who had had it in their garden in Hampstead for many years.4 Julian Huxley was a well-known biologist, secretary of the London Zoological Society (1935–42), and the first director-general of UNESCO (1946–48). He and his wife Juliette, who had trained as a sculptor, knew that Moore was interested in natural forms, and especially liked bones for their texture and structural complexity. Moore recalled how, shortly after the skull arrived at Perry Green, he began to draw it:

The first day I drew the whole skull to find out its general construction; gradually I became amazed at the complexity of it, and my interest and excitement grew greater each day I worked. By bringing the skull very close to me and drawing various details I found so many contrasts of form and shape that I could begin to see in it great deserts and rocky landscapes, big caves in the sides of hills, great pieces of architecture, columns and dungeons.5

These studies resulted in one of Moore’s most celebrated graphic albums, the Elephant Skull etchings (1969–70), and a sculpture, Two Piece Points: Skull (1969), which is the only work he conceived specifically to be made in fiberglass, a material he found most suitable for having qualities so similar to bone-color as well as a combination of strength and lightness. Moore had started to make fiberglass versions of some of his larger works a few years earlier, to allow monumental sculptures that were too big or heavy to travel to be included in touring exhibitions. Two of the works on show at Houghton Hall—The Arch (1963–69), developed from an enlarged fragment of bone, and Large Reclining Figure (1984), the monumental version of a small work from nearly five decades earlier—are among the most significant examples.

Moore’s fascination with nature and the landscape places him within a tradition that harks back to romantic painting and poetry, gothic architecture, and prehistoric standing stones. It has sometimes been remarked that this makes him a quintessentially English artist. Yet these ideas, combined with his humanism and transcultural outlook, have proven to have a truly universal appeal, and have contributed to make him an artist recognized and admired the world over.

The epigraph is from Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, ed. Herbert Read (London: Cassell, 1934), pp. 29–30.

1Donald Hall, “Henry Moore: An Interview with Donald Hall,” Horizon (New York), November 1960, p. 103.

2Henry Moore quoted in “Sculpture in Landscape,” Selection (Winchester), Autumn 1962, p. 12.

3Richard Calvocoressi, “Foreword,” in Henry Moore: Late Large Forms (London: Gagosian, 2012), p. 17.

4The skull had been given to the Huxleys by an acquaintance in Kenya in the early 1960s.

5Henry Moore, statement, in Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, ed. Alan Wilkinson (Aldershot, UK: Lund Humphries, 2002), pp. 297–98.

Adapted from the exhibition brochure accompanying Henry Moore at Houghton Hall: Nature and Inspiration, presented by Houghton Hall in collaboration with the Henry Moore Foundation, May 1–September 29, 2019; artwork reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation; photos: Pete Huggins