Michael Auping is an independent curator and art historian. He is well known as a curator and scholar of Abstract Expressionism, and has organized exhibitions of Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, and Clyfford Still. He has also organized major exhibitions of Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Susan Rothenberg. His latest book, 40 Years: Just Talking About Art, was published by Prestel in 2018.

In the evolution of abstract painting, provocative examples abound of a particular landscape inspiring an artist to create a critical body of work—one that is revealing not simply of the place, but even more so of the artist’s thought process. Paul Cézanne’s Provençal mountains and the gardens of Arshile Gorky’s Armenian homeland were visual scaffolds for the semiabstract works they would create and the types of gestures they would use to forge a bond between place and the road to abstraction.

In some cases, the place was as much imagined as physical. Joan Mitchell’s extended La Grande Vallée series derived from stories told to her by her assistant about a hidden valley in Nantes, Brittany, where she and her cousin would escape from adults to have imagined adventures. Mitchell never saw this haven, but nonetheless painted twenty-one canvases evoked by her assistant’s recollections. Landscape poems by the Chinese Tang Dynasty poet Han Shan served as a source for Brice Marden’s Cold Mountain paintings. Cy Twombly’s painting cycle Fifty Days at Iliam reimagines Homer’s epic poem about the ancient city and its environs during the final days of the Trojan War. All of these artists used a place or context to inspire a particularly visceral side of their art. Through their radical and often deeply romantic visions, an unusual, not easily definable bond developed between abstraction and that broad category we call landscape.

Mark Grotjahn’s Capri series adds an intriguing layer to this rich genre of the abstract landscape. If Grotjahn had wanted to pay homage to Twombly’s Fifty Days at Iliam, he could have titled his project Twenty-four Hours in Capri. It began with an invitation: to make a new group of works to exhibit in Casa Malaparte on the Italian island of Capri for only one day. A modernist house designed by the writer Curzio Malaparte in the late 1930s, Casa Malaparte is perched on a hilltop, with astutely placed windows that look out onto some of the most stunning vistas of land, flora, and sea in the world. This was a house that Grotjahn had admired from afar for years, having seen it in the 1963 New Wave film Contempt, directed by Jean-Luc Godard and shot mostly at Casa Malaparte.

“I’m a sucker for exotic locations associated with art and artists,” Grotjahn confesses, “and I wanted to start something new—a body of work that would take me away from what I had been doing. I approached the whole thing as a journey, not just to Capri, but within my painting.” That journey would eventually result not only in installing a group of works at the house, but in multiple new series of Capri works over a period of years. In the end, the subject of the Capri paintings would not just be a tribute to Casa Malaparte, but a meditation on the tensions and internalizations that exist between art, fantasy, and nature.

The narrative evolution of the paintings that would result has an appropriately—perhaps unconsciously—filmic quality, involving painterly close-ups and jump-cut-like dislocations. Rather than traveling to see the house and its surrounding landscape firsthand before beginning the series, Grotjahn began the project six and a half thousand miles away from Casa Malaparte, in his Los Angeles home and studio, where he rewatched Contempt several times.

Throughout the “Capri” series, abstract painting and nature are both conceived as the sites of Darwinian struggles.

As removed as this strategy might sound, Godard’s film offers an interesting prelude to understanding Grotjahn’s strategic psychological relationship between abstraction and nature. Starring Brigitte Bardot and Jack Palance, Contempt is primarily about pitting personal relationships against career ambitions. A subplot, however, pits culture (in the form of the starkly minimalist architecture of Casa Malaparte) against the natural beauty of Capri. Throughout the film, windows offer views of the island’s trees, hills, and cliffs. Rather than making us feel closer to nature, however, Godard manages to emphasize his characters’ alienation from it. Actors seem trapped not only in their own self-serving lives but in the elegant austerity of Casa Malaparte, caged inside the modernist box as they gaze mournfully out the windows at the natural beauty around them. Grotjahn’s paintings present a different view that could be described as being in nature itself. Without depicting it, he uses painting as a paradigm for nature’s gritty fundamentals. What he showed on the walls of Casa Malaparte are like earthen biopsies. One could call them pre-landscapes, capturing Capri long before the house was built, when the island was just beginning to support the plants and trees that cling to its rocky, volcanic surface.

The history of the early relationship between abstract painting and the evocation of nature or landscape is inextricably tied to the history of painterly gesture. The intuitive spreading of brushstrokes across a canvas has long been a signifier for nature’s organic forms and its dispersed field. Over the course of two decades of making “abstract” paintings, Grotjahn has found unique ways to re-form his gestures to reflect the project at hand, whether that has meant hiding his brushstrokes under the surface of shining geometric forms or, as in this case, using his marks to create an analogy to nature’s dynamic process.

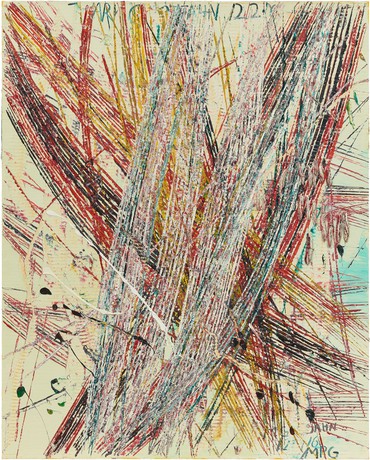

Throughout the Capri series—which encompasses multiple subseries, including New Capri, Capri, Star Capri, and Free Capri—abstract painting and nature are both conceived as the sites of Darwinian struggles. In order to survive in their respective ecologies, both painting and nature must carve and dig their way into existence. In the New Capri series, the first iteration of the project, gestures are elementary, the beginning of Grotjahn’s process, which is analogous to preparing soil for planting. After covering cardboard sheets with thick monochromatic layers of paint (red, yellow, green, black), he digs into the ground with a palette knife, turning this tool of fine painting into a kind of plow. Cutting through layers of paint, and often into the cardboard support, he excavates color as if it were metal deposits embedded in rock and earth. Color is literally pulled to the surface in the form of spectral ridges and blobs of paint that suggest an aerated picture plane. The paintings look as if they should smell of raw earth.

Although they are ostensibly abstract, Grotjahn’s marks have a funny way of evoking the trees and plants that grow up out of the rocky soil of Capri. Hanging near the windows of Casa Malaparte, the paintings conjured gestural allusions to the weed-like plants, pine trees, and their needles, all fighting their way through the rocky surface of the island.

When you start looking, you see natural motifs everywhere in Grotjahn’s work.

Grotjahn is very aware of the history of abstract painting and its engagement with nature, if not landscape. The Capri project seems to particularly channel Abstract Expressionism, most poignantly the work of Clyfford Still and Jackson Pollock. Like Still, Grotjahn uses the palette knife to create surfaces that reference earthiness in their gritty colors and mud-like textures. The Capri paintings echo not only Still’s use of the palette knife, but also the idea that painting is an internalization of nature. Still remarked that his early semi-figurative “landscapes” were about being “preoccupied with the figure in landscape, with overtones of man’s struggle and fusion with nature.” Pollock put it even more directly: When asked if nature was the model for his gestural abstractions, he responded, “I am nature.” The Capri paintings involve a similar kind of absorption, predicted in one of Grotjahn’s early performances, in which the artist cut into his own skin, prompting blood to flow. His body stands in as both “painterly” ground and nature’s ground, echoing Pollock’s proclamation.

In nearly all of the New Capri paintings, Grotjahn’s name or initials are embedded in the surfaces. This has been interpreted as a tongue-in-cheek reference to a time when artists assertively signed the fronts of their canvases. In this context, however, Grotjahn seems to want to bury himself in the chaos of the gestural landscape.

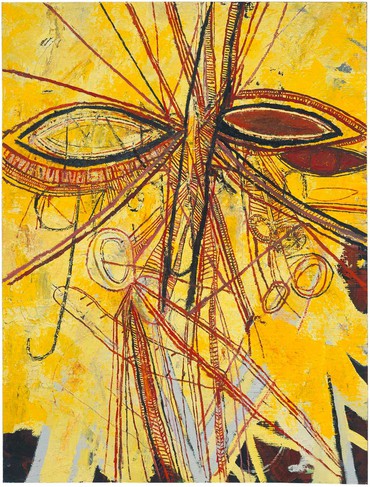

In a few of the New Capri paintings, eyes peek out—remnants from Grotjahn’s previous series of Face paintings, which never depict a full visage, but rather fragments in a weedy field of gestures. Reexamining the Face paintings through the lens of the Capri project, the “faces” seem less like gesturally deconstructed portraits than like a glimpse of someone looking out to the viewer from within a dense jungle. The Face paintings are about faces embedded in nature, and actually constructed from tree branches and leaves. Grotjahn acknowledges these transformations, pointing out in particular the “veins of leaves, feeling like human veins.”

You can glimpse historical flashbacks in these paintings, from the textured tree people in Max Ernst’s Age of Forests (1926) to the image of mud-covered captain Kurtz peering out of his jungle of darkness.

When you start looking, you see natural motifs everywhere in Grotjahn’s work. One of his first exhibitions consisted of flower drawings that replicated those done by his grandfather, with whom he drew for hours at a time as a child. There are also the seed drawings he made starting in the late 1990s, in which small arcing lines are brought together in colorful chains. The larger arcing gestures that occasionally come together in the New Capri paintings could be echoes of those seeds. “Some things you just can’t get away from,” the artist has said. “Even if you are trying to think about something else.” In Grotjahn’s work, nature is one of those things, whether they be abstracted seeds, horizons, and sunsets, or the galactic vortex that appears in the early Butterfly paintings.

After Grotjahn eventually traveled to Capri to install the New Capri paintings on the walls of Casa Malaparte, his confrontation with the island’s dramatic terrain inspired a much larger body of work. Spending time looking out over the cliffs seems to have brought about a more inclusive dialogue between the lofty airiness of the place and its earthiness.

Returning to his Los Angeles studio, Grotjahn began to work on larger sheets of cardboard. The scraping and digging continued, but the gestures were stretched out to fill the larger sheets, which he mounted on stretched canvas to make them easier to handle and hang. The other benefit of the additional support was that it allowed the artist to more fully reveal the residue of his scrapings, which accumulated at the edges of the cardboard. One of the best viewpoints for these paintings is from the side, leaning your head on the wall. It’s here you really get a sense of Grotjahn’s colorful excavations.

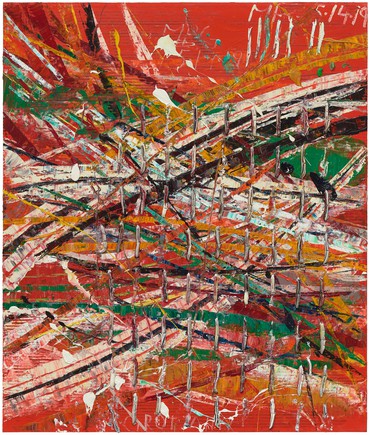

As with the earlier works, gestures and scrapings accumulate into motifs. Rudimentary grids are carved into the surface of many paintings. These are not the grids of Minimalist precision, but more like old fences or wobbly vines on which paint has been allowed to “grow.”

In these later Capri works the process of scraping has rendered cylindrical globs of paint. Rather than let them fall to the ground and dry into useless hunks, Grotjahn creates his own pictorial ecology, attaching the wet cylinders back onto the painting’s surface. Earlier generations of artists, from Frank Stella to Anselm Kiefer, have acknowledged the reuse of paint as a semi-alchemical process referring to “the natural, organic growth of painting.” Grotjahn calls his painterly cylinders “slugs,” the slimy relatives of earthworms.

Or could these paint pods be chrysalises, the cocoons where butterflies incubate before they take to the air? Arguably the most well-known of Grotjahn’s works over the past two decades are his Butterfly paintings, in which triangular planes of paint create slivers of light and color that vector back into an off-centered space in the picture. For Grotjahn, these planes suggested the wings of butterflies.

Take it one step further and you see that in some paintings the gestural grids have exploded into ecstatic fields of multicolored lines crossing each other, resulting in starlike images that seem to vibrate over the surface of the painting. These Star Capri paintings evoke a blurry movement that, yes, could be the animated rhythms of fluttering wings.

As if to cap off this conjectured narrative, Grotjahn installed bronze sculptures at Casa Malaparte, overlooking the hills of Capri. He titled them Butterflies. These rugged, semiabstract forms derive from the same cardboard “ground” as the Capri paintings: the artist fashioned the primitive, emblematic butterflies using parts from the production of other sculptures, cast from pieces of discarded cardboard boxes. Butterflies have long been symbols of beauty in its freest and most lyrical sense. Today, they are also a symbol of fragility, their dwindling numbers an indication of an unhealthy planet. In its own fragility and old-fashioned sense of freedom, abstract painting in the twenty-first century is analogous to the butterfly.

More than documenting the visual specifics of Capri, these paintings reflect what the island represents as a natural wonder, but a wonder in its most fundamental sense.

It is hard to know whether you see such images in these paintings or simply imagine them. At the end of the day it doesn’t matter, because the history of modernist abstraction has often been about a reimaging of nature’s inspiring allusiveness. More than documenting the visual specifics of Capri, these paintings reflect what the island represents as a natural wonder, but a wonder in its most fundamental sense. The distinction between landscape and nature springs to mind when viewing Grotjahn’s Capri paintings. Like painting, landscape has always been a fiction, invented and framed. Nature is something else, and it is this something else that abstraction at some of its best moments taps into. It is an old-school challenge that Grotjahn embraces with the Capri series, one that goes back to the beginnings of abstraction, when Vasily Kandinsky’s Murnau landscapes and Piet Mondrian’s trees imploded into personal, dare we say spiritual, investigations into our deeper connections to nature. Those days seem long gone and mostly forgotten by many of Grotjahn’s generation, who are more the progeny of Andy Warhol and his wallpaper flowers. As one artist put it, “This world we live in is so man-made, nature has been banished to the land of kitsch.”

In a recent conversation, I was surprised to hear Grotjahn cite Kandinsky’s book On the Spiritual in Art (1911) as a fundamental inspiration for his decision to become an artist. That conversation and these paintings do not suggest that Grotjahn is a conceptual abstractionist with a practice steeped in popular culture and critical theory. At the very least, the island of Capri seems to have taken him back to a time when art, and abstraction, involved less critique and more romantic animism. Poised between a recognition based on memory and the seductive promise of a new kind of abstract nature, these paintings are emblems of the immanence of nature in the mind of the painter of abstractions.