Alison M. Gingeras is a curator and writer in New York and Warsaw, and most recently the editor/author of John Currin: Men. Jamieson Webster is a psychoanalyst in New York, faculty at The New School for Social Research, and author most recently of Conversion Disorder (Columbia, 2018). They frequently collaborate and write together, most recently on anality, utopian communes, guilt, and the artists Bjarne Melgaard, John Currin, and Jordan Wolfson.

Paul B. Preciado is a philosopher and curator and a leading thinker in the study of gender, sexual, and body politics. A former Fulbright fellow, he holds a PhD in the philosophy and theory of architecture from Princeton. From 2014 to 2017 he was curator of public programs at Documenta 14 (Kassel/Athens), where he started the project The Parliament of Bodies. Photo: Marie Rouge

jamieson webster/alison gingerasPaul, we found a poem we thought you might like, Paul Éluard’s “Interior” [1921]:

In a few seconds

The painter and his model

Will run away.More virtues

Or fewer misfortunes

I notice a statueA kind of almond

A varnished medal

To my greatest boredom.

paul b. preciadoThank you. Éluard is one of the first poets I read in French, but I haven’t reread his work in years. I wonder how we’d read this poem today; with certain variations, I’d imagine. Like this?:

In a few seconds

The male white painter and his black female model

Will run awayMore virtues

Or fewer misfortunes

I notice a statue . . .

Or how would it be if it were a black female painter and a male white model, for instance.

JW/AGSorry to hear you’ve been sick with corona and it hasn’t gone away. Can you tell us about your experience of the virus?

PBPI’m better. A lot of ups and downs. It was really unsettling, as I lost sight in my left eye—the same way corona can affect your smell, it can affect the optic nerve. You don’t think you’re just losing vision, you think you’re dying, and you don’t have the sense that physicians can tell you something coherent anymore; they tell you this and that, and then do this, and maybe we’ll pick you up in an ambulance, and you think: maybe? But it was the first summer in my life that I was able to relax. I didn’t do anything.

JWDid you ever think doctors could tell you something coherent? Maybe we’re just realizing how incoherent they’ve always been?

PBPI’m obsessed with the issue that we’re in a paradigm change. We’re right on the edge, like in the time of Galileo, when the paradigms for the production of truth were changing. The words we use are the same but the meanings are changing constantly and sometimes there’s a void behind the word. I’m not saying that what came before was coherent and true, you know I’m critical of the medical regime, but for a time it made sense for some subjects, it could be decided what was normal and what was pathological. I wish we could make a map of these changes—changes to the world that was created by patriarchy and colonialism—but what’s tricky is, we don’t know yet how new standards of truth will be produced.

AGWe don’t know what’s going to emerge from all this.

PBPExactly. Today words are becoming orphans: they’ve lost their normative meaning and they’re looking for new significations, other ways of relating to reality. And this, I think, is good news. And I think that more than ever before, we have the impression that we’re participating in the undoing and redoing of history. We’re globally conscious that we’re doing this together. And when I say this, we don’t have to agree, there are huge conflicts of course, as well as extreme forms of violence and economic and political nodes of the concentration of power, but we’re fighting together to create a new paradigm.

AGDo you think the catalyst for this was the lockdown? A first-ever global caesura?

PBPPartly, yes. For me, this rupture wasn’t just a question of the medical or political management of a collective body; it was an aesthetic crisis. As subjects we engage in reality as sensitive living bodies, and as political subjects we always think of action, but by not doing anything, by not rapidly engaging, we had to think about our living bodies. Extreme conditions brought about political awareness. Confinement and sudden confrontation with vulnerability and death created a moment of global aesthetic and political awareness.

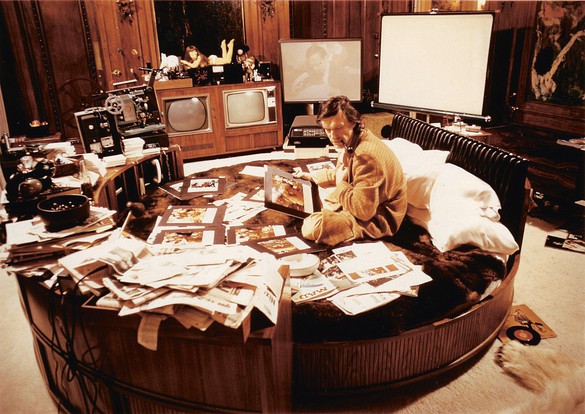

JW/AGThere’s a love/hate of interiors, as an old paradigm, in your work. This is perhaps best seen in your ambivalence toward Virginia Woolf and the consulting rooms of psychoanalysis, which you see as the all-too-bourgeois spaces of domestic daydreaming. These spaces, you also show, are easily co-opted, from bedroom to museum, by necro-capitalism, which you model on the scene of Hugh Hefner in his bedroom in the Playboy Mansion surrounded by cameras, telephones, audio recorders, and TVs. As you say, this is a space in which we evade the fact of war. Can you speak about interiors?

I think that more than ever before, we have the impression that we’re participating in the undoing and redoing of history. We’re globally conscious that we’re doing this together.

Paul B. Preciado

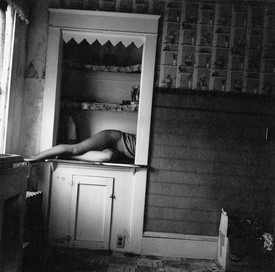

PBPI’m just questioning whether the house—the family home, for instance—can be a place of growth and realization, as Western liberal democracy has pretended. A good deal of institutional critique has referred to public and state institutions such as schools, hospitals, prisons, etc., as places of discipline and confinement, but the house is never sufficiently studied and criticized. Virginia Woolf is already halfway into this critique, since she feels trapped in the position of a woman without a place to write in the house. When she claims the need of a room for herself to be able to write, she is identifying the possibility of self-confinement and privacy as a way of extracting her female body from the disciplinary rituals of reproduction and heterosexual domesticity. Virginia Woolf’s room is the opposite of a home; she wants to dedomesticate the home by setting a room of the house outside the patriarchal rules. We could say, using the terms of Gilles Deleuze, that her room is a feminist fold of the domestic space. But of course she makes this claim from her position as a highly privileged bourgeois white woman. So, yes, in modernity, being able to construct and protect your own interiority is a form of political privilege.

In the case of psychoanalysis, don’t you find it interesting that Freud decided to treat his so-called patients in his own private domicile, having them share his home? Why is the patient going to the place of the analyst, for instance, and not the opposite? Psychoanalysis implied a move from the hospital into the domestic realm as a place for therapeutic treatment. This move was partly due to the not-yet-established condition of psychoanalysis as a clinical discipline at the beginning of the twentieth century, but curiously enough, the practice of domestic treatment remains, despite the institutionalization of psychoanalysis in the century’s second half. The problem is that this displacement represents a privatization of the words of the so-called “patient.” Being at the analyst’s house is also coming into the analyst’s interiority.

In both cases—in the feminist struggle for a room of one’s own as a quest for an interiority not defined by heteronormative demands, and in psychoanalysis as a practice of exploration (or creation) of the patient’s interiority (an interiority that can also be called the unconscious)—to invent dissident cultural practices means also to invent new spaces, or to inhabit traditional spaces differently, to fold them, segment them, open them. This is why I’m so interested in a shift that took place after World War II: the relocation into the house of activities of economic production that were traditionally placed outside the domestic realm. I was fascinated when I discovered how Hefner, the creator of Playboy, intentionally confined himself in his Playboy Mansion and, surrounded by media technologies, started a new form of production directly from his rotting bed. My contention is that the highly media-connected pod he created was a laboratory for the building of contemporary digital interiority.

JWI’m curious about your thoughts on psychoanalysis; I can’t say I’m not sick of my office—it’s set up like a communal space where patients feel invited to stay, lectures sometimes take place in one part of it, it’s confusing what’s even an office or who’s even a doctor—but, still, it’s easily routinized. Zoom work, which can happen anywhere and on less of a schedule, feels like it loses the body and affective intensity. These folds are so fragile.

PBPPsychoanalysis came into being at the end of the nineteenth century, at the climax of patriarchal, colonial, and imperial times. As our time is dominated by the coronavirus, that time was dominated by syphilis, and sexuality—questions of reproduction, marriage, lineage, sexual difference—is therefore at the core of psychoanalytic discourse. What corona will do in relation to today’s changes in physics, and in the idea of life and the human, will be a major transformation. I wish psychoanalysis could engage the political condition of the unconscious, that it could question the patriarchal/colonial model of the body and the normative idea of subjective interiority. I’ve been trying to think about what my problem with psychoanalysis is, and I think it’s the power position that psychoanalysis has had about the interiority of the subject—a sort of monopoly over dreams and imagination, and an obsession with the family plot. It’s not so much about doing away with this power but more the idea that psychoanalysis is at odds with reality now, with what’s shifting. So can it work the same way? I say this, and yet I want what I call a “mutant psychoanalysis,” not a quest for interiority but a space for collective transformation of consciousness. I have so many questions, and Jamieson, you and I should talk—I don’t think you’re representative of the kind of psychoanalysis that’s practiced.

JW/AGWhat kind of interiority is (or is not) a body?

PBPThis is a very interesting question in terms of the political history of the body. Bodies have not always had interiority. In a certain sense, if we think about the premodern Western body, it is a flat body, a skin on which the law is inscribed as a sort of somatic writing. Torture and social blood rituals are forms of inscription of the law on this body without interiority. With the three major monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, a new form of interiority is invented, but through what I could call an architectural dualism between flesh and the spirit. The body—still a thick skin, a facade of flesh that encases bones, blood, water, and semen, for instance—is nevertheless seen as hollow, empty, to be able to host the soul—which, although strictly speaking nonmaterial, needs a nest, a container. Interiority always demands a shell, a skin, a membrane. In Christianity, the body is thought of as the temple (in a strict architectural sense) of the soul. Here the interior of the body is by definition invisible. This theological understanding of an immaterial interiority of the body has survived in more secular notions of the unconscious—in psychoanalytic theory, for instance, as well as in contemporary transhumanist theories that see the soul as a software that can be channeled in and out of different bodies.

In modernity, this premodern tradition of the flat body enters into conflict with another understanding of the body as a full space. In the sixteenth century, with Vesalius and the advent of anatomy, the body is no longer pure exteriority or skin. It becomes an endless collection of organs. This might be one of the most important transformations produced by anatomy: interiority is invented as a visible space that can be accessed, described. The interior of the modern body is a museum, an exhibition space that can be visited. This form of visual rationality brings with it the understanding of a body as an automaton, a collection of pieces that work according to a master plan. Modern anatomy—but also slavery, the market, functionalism, and Taylorism—invented the body as a private (or unprivate) object. It is an enormous political problem that we continue to work with this notion of body as object.

Besides, the relationship between exteriority and interiority is going to become more and more complicated as many of the functions of the “soul” or the “spirit” are externalized and transformed into semiotechnical prostheses. This isn’t a question only of computers and artificial intelligence; the most important externalization of bodily (and/or soul) functions starts with writing. So my last answer to your question is that the interior of the body today lies paradoxically outside what we know as the physical individual “body,” that object invented by modern anatomy. This is why, instead of using the notion of “body,” I propose to speak about the “somathèque,” looking at the body as a living political archive composed not only of biological organs but also of artificial political prostheses, social institutions, fictions, codes.

This might be one of the most important transformations produced by anatomy: interiority is invented as a visible space that can be accessed, described. The interior of the modern body is a museum, an exhibition space that can be visited.

Paul B. Preciado

JW/AGYou write about your need to travel as far as . . . Uranus, to get out of the coded systems inherent to this world. You’re the consummate nomad. What did the coronavirus lockdown and the new border patrols do to you? Is it still possible to feel alive?

PBPI think thanks to the coronavirus I have managed to sleep in the same bed without moving for five months. It has been a foundational experience of change for me.

JW/AGThe lockdown certainly brought to the surface questions of policing, passivity, confinement, detention. This has transformed into a call to defund/abolish the police. It’s surprising to hear mainstream media in the United States even consider a proposal this radical. On the other hand, as Judith Butler has noted, everything in the United States is playing out around the question of the superego, Trump being a figure who defies the policing of identity politics. Is this a series of displacements from the general question of surveillance? Even if our telecommunication devices are our new jailors, the police still insist on the traditional strategy of physically surveilling, killing, or jailing Black men, at least in the United States.

PBPI think we’re at the end of one historical and political regime and moving toward a new one. This is a time of planetary transition. With digital and biological technologies, traditional notions of surveillance are shifting rapidly. At the same time, the biopolitical techniques of colonial and postcolonial capitalism, such as imprisonment and police surveillance, have not yet been overcome. This is why, in my view, hyperbolic forms of violence, lynching, and physical punishment coexist with new practices of management and control of the population. I’m not saying that the new techniques of biosurveillance and digital control are not violent, but that they work in a different way. They operate in the area of interiority that we were talking about before, for example, or of the individual body and the brain, and not so much at the level of traditional institutions of confinement.

JW/AGAfter a public breakup with Virginie Despentes, you wrote about a kind of skepticism about notions of romantic love, or, dare we say, a transcendence of them. Then the lockdown happened, and as you wrote in Artforum, you got sick and imagined that with this great mutation, wherever you are, single or coupled, life will now stand still like this forever. Skin contact will only be afforded to those who are trapped with their pandemic partners. You wrote a letter to an ex and put it in a recycling bin. What can we say, to recycle the endlessly recycled and reified title of Gabriel García Márquez, about love in the time of corona?

PBPWhen I broke up with someone whom I’d thought I would live with forever, I had a moment of the negative theology of love. I learned that love wasn’t romantic love. This is such a banality that I feel sorry I only discovered it when I was forty-five. How silly! But this doesn’t mean I don’t believe in love. Love is not happiness in a couple; love is a disturbing truth that transforms who you are, that mobilizes memories, affects, and desire in unexpected ways. In a sense, for me love is revolution. And in this respect, the corona times as times are not just revolutionary times, but also times of love.

JWYou’re so optimistic about living through this time?

PBPIt’s true. I’m pathologically optimistic. When I was sick, I did go through a political depression—I was disappointed by politicians and how they dealt with the crisis, by a kind of chain reaction of countries moving toward the right when we need the opposite. But I think optimism is a political duty. It’s not the idea that things will be better—that, I don’t know—but the desire to transform things. Even beyond that, this is an extraordinary moment, a revolutionary time, and for a philosopher I can’t think of a better moment to be alive, to be able to participate in this. And I want to let this transformation vibrate in my thoughts, almost as if I’m becoming a receptive organ for it. I’m not interested anymore in stable institutions, like couples, families—there can be joy as much as misery there, but for me, this is not my way of life, it’s not what I have to offer, and I want to jump into the sense of chaos and change in the world, which I like. Maybe that’s because I was born into the end of fascism in Spain, and everyone around me was dead—they kept living but they’d been killed within, since fascism is a structure of the subjective colonization of a subject’s desire. That was so scary for me. So in relation to what’s happening now, it’s much, much better, no matter how difficult it looks.

JW/AGI think in New York City we don’t know if we’re dead or alive. There’s something very exciting happening right now, the feeling that the city could be something other than what it was, but there’s also what’s happening in the rest of the country—the election, overt racist violence, armed militia. It’s scary, and makes it feel hard to throw yourself into the transformation right now.

PBPThe situation in the United States is extremely complex. Looking at it from Paris, we’re trembling, especially about the possibility of a civil war, but we do have the sense of the United States having a history for the first time. We always spoke about the country as if it was its early morning, it had this newness. And suddenly, and again I’m optimistic, no matter how difficult what you’re going through, and I’m a little Hegelian here, but this is your beginning, the beginning of your historical consciousness. So this is absolutely necessary. And maybe it has to become even more—

AGDegraded. Maybe it’s a Leninist moment, the whole thing has to blow up.

PBPI also see the dangers ahead: in order to stop or prevent these epistemological and political paradigm shifts that are upon us, the state could go into an extreme form of technofascism. That would be even worse than the fascism in Spain in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Today we’re living under advanced systems of surveillance and biotechnology at the same time that reactive notions about the nation, the state, and the family are being enforced by right-wing governments.

JWDon’t you think Trump is the weirdest hybrid? He’s an unmoored, euphoric figure, who represents no institution at all, at the same time that he’s a complete technocratic fascist. He’s an old-school family ideologist surrounded by his clan. He’s almost like a surrealist assemblage: if you had to pile all of these images on top of each other, it would be this man.

PBPYes, absolutely. Yes, I totally agree with you, but it’s also a fiction. Probably you know Louis Marin on absolute power? He basically explains the king as having two bodies: a physical, mortal body and something else. It isn’t physical, it’s a fictional body that is able to incarnate the nation state and sovereign power. That’s why, when a king dies, it basically doesn’t matter, because we put another king into the same envelope. For me, Trump is a little like that. And this is precisely the problem. [Vladimir] Putin, [Jair] Bolsonaro, all of them at this moment, they’re fictional; they’re hyperpatriarchal, hyperracist content for the violent envelope of the nation state. Their bodies are—

AGAlmost like a meme!

PBPAbsolutely, a transcendental meme. They’re bridging the lowest and the highest. And this is the danger—this is why it’s not just a Trump or a Bolsonaro. We could never have imagined these technofascists of the twenty-first century. A room of ten writers couldn’t have invented a character like Trump, because he’s way too outrageous, too odd and ridiculous, right? And I think that’s exactly what’s interesting. And that’s why the radical left is struggling with this moment. Trump, for instance, his physical body, is incarnating this political fiction of a technopatriarchal racist power. The radical left must propose a counterbody. I’m thinking about bodies like Angela Davis in the 1970s, bodies that could incarnate collectively.

JWWe need an alternative.

PBPExactly. But it isn’t easy for the subaltern movements, racialized, trans, or nonbinary, to incarnate those fictions because our bodies are precisely what’s at stake. Our bodies are the ones that aren’t being fully recognized as political subjects. The problem is that subaltern bodies are mostly visible and recognized as victims, objects of violence, killed bodies. It’s very difficult for emergent figures to manage to incarnate a political living fiction able to condense collective desires of transformation.

AGMaybe that’s why, in the summer of 2020, the Black Trans Lives Matter movement in New York presented such an incredible coalition, one unthinkable a year ago. Rainbow capitalism was completely shunned and everyone rallied around this amplification of Black Trans Lives. I think this was in the spirit of what you’re talking about, not a singular figurehead.

PBPAbsolutely. Black Lives Matter, the trans and gender-queer movements, Ni una menos, the migrant movements, the indigenous movements, the sex workers, the queer-crip . . . all of them are constructing critical counterfictions, demanding the enlargement of the democratic horizon in order for new bodies and new subjectivities to be recognized as political subjects. This is a very difficult moment, but also an extraordinary one.

“New Interiorities” also includes: “Becoming Together” by Alison M. Gingeras and Jamieson Webster; “Living Death” by Jacqueline Rose; “Vera, Lateral Puncture” by Deana Lawson; “You Should Leave” by Alissa Bennett; and “Resting Place” by Miciah Hussey