Susan Breyer is a Latina art historian and writer. She joined Gagosian in November 2018.

Latinx artists’ incisive and diverse contributions to contemporary American art deserve our devoted attention. These innovative and often invisible practitioners extend and expand upon a rich history of Latinx art in the United States—which includes the oeuvres of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Carmen Herrera, and Ana Mendieta. With Latinxs now accounting for more than half of the United States’ population growth, and as US art and academic institutions respond to calls for the representation of BIPOC artists in exhibitions, collections, publications, and dialogues, it seems that public awareness around Latinx art—including the ways in which Latinx artists are currently reshaping the cultural landscape—is increasing significantly. Notably, through their dynamic and often collaborative explorations of art history, race, socioeconomics, immigration, pop culture, and craft, among many other topics, contemporary Latinx artists are debunking purist myths; rewriting narratives around Latinidad; and carving out new, accessible, antiracist spaces for art making and viewing. Indeed, it would seem that the historic marginalization of Latinxs has added an inimitable depth of perspective to these artists’ work.

“Latinx” is an inclusive, gender-neutral term that simultaneously unites people of Latin American and Caribbean descent living in the United States and implies heterogeneity; people who identify as Latinx come from an array of racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds. As a category, the term’s perimeter is not fixed, but rather fluctuates to encompass the multiplicities and evolutions of the populations it references. In a recent panel discussion held by El Museo del Barrio, New York, to accompany its Trienal 20/21, artist and curator Elia Alba remarked, “I always talk about [Latinx] as a space. . . . To think about all these different identities . . . how [they] intersect, how they’re different . . . the destination is Latinx.”1 Meanwhile, author Arlene Dávila defines Latinx art as “a project . . . a blueprint for the acknowledgment and identification of the work of artists who have been consistently bypassed by the American and Latin American art history.”2 As a coalescing form, then, Latinx art also benefits from a viewer’s expansive mindset, with an eye toward equity for underrepresented individuals.

any first- or second-generation citizen who migrated to a new culture can understand the feelings of a hybrid identity and coming to terms with one’s role and value in each culture.

Glendalys Medina

While explorations of transculturality appear across Latinx art, each artist proffers unique insight into the diversity of contemporary Latinx experience. Interdisciplinary artist Glendalys Medina, born in Puerto Rico and raised in the Bronx, draws from their own multicultural background to create work that layers and amplifies Latinx, Black, and indigenous voices. Medina’s formative environments were saturated with urban graffiti, hip-hop jams, the sounds of the Fania All-Stars, and a profound longing for the Caribbean. In turn, the artist’s striking geometric abstractions integrate bold, energetic forms with Taino (indigenous Caribbean) motifs and rhythmic patterns evocative of melodic contours. Medina asserts that “any first- or second-generation citizen who migrated to a new culture can understand the feelings of a hybrid identity and coming to terms with one’s role and value in each culture.”3 Thus, while viewers can certainly delve into the artist’s specific references, there is also space to consider how intersectional reality defines contemporary society.

An indelible connection to family—as guardians of culture, tradition, and personal histories—and local community crucially informs the practice of New York–based artist John Rivas. Rivas’s raw, dexterous works in a range of mediums incorporate objects, customs, and imagery that honor his immediate friend and family networks and quotidian environments, which are colored by the richness of shared Salvadoran heritage. “I base my work around my life and my life around my work. I was born [in the United States] but at the end of the day, my traditions, the things I know, even history come from [El Salvador],”4 Rivas has reflected, and this link is evidenced not only in the individuals he depicts, but in the topographies of his compositions—where clusters of dried beans form ears and delineate facial curves, while bands of thread stitched attentively across pictorial segments nod to his grandmothers’ sewing practices. For Rivas, centering people of color from El Salvador and from New Jersey’s Salvadoran-American community (where the artist was born) is not only a way to underscore these individuals’ resilience and fundamental roles in society, but also a political act. “I’m the type of person who believes in fucking up the white space,” says Rivas. “People from Latin America, these people in the background, I want to solidly [put them] in front.”5

A photographer and trained psychoanalyst who works between New York and Panama, Rachelle Mozman Solano has also pictured family members within her work. In the series Casa de Mujeres (2010–11), for example, the artist’s mother poses as three distinct female figures inhabiting a single fictional Latin American home. Together, the women enact domestic activities that demonstrate deeply embedded racial and class tensions. While the artist’s relationship to her primary subject infuses each frame with a sense of familial intimacy, Mozman’s mother also symbolizes the impact of colonial and neocolonial forces on daily race and class dynamics. Mozman cites a desire to engage “the history of colonization, white supremacy, and its connection to present-day policy and politics” as a driving force behind her artistic practice, and recognizes “the intergenerational effect of this history on the body and the psyche.”6 As individuals who have lived—in both private and public settings—the effects of colonization, Mozman’s family members breathe humanity into flattened histories and serve as a powerful conduit for visualizing overt and subtle subjugations of marginalized people.

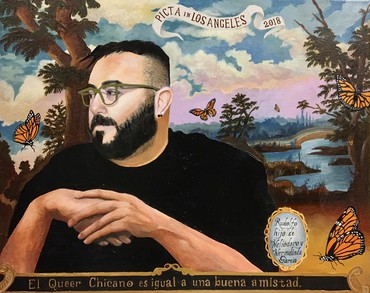

Los Angeles–based Chicano painter Joey Terrill likewise imbues preexisting sociocultural narratives with personal depth and nuance. Discussing Chicano perspectives and art in the 1970s, Terrill observed that “artists took inspiration from exploring our Mexican roots and Aztec mythology as well as cultural references related to cholos, homeboys, lowriders, pachucos, mariachi music, and political history. Your family was the most important thing and your place in the family structure was well defined. [But this] wasn’t authentic to my experience as a second-generation Chicano growing up in Los Angeles with Rocky & Bullwinkle cartoons, watching pop music shows featuring British Invasion bands and go-go dancers while reading Mad magazine. I wanted to provide a space where an embrace and celebration of my queerness could be found.”7 For more than forty years, Terrill has challenged the heteronormative limitations he perceives in American art by making paintings that depict his friends and lovers, and that draw on his own experience as a long-term HIV survivor. He is currently painting a series of portraits titled Mi Casta es Su Casta (My caste is your caste) (2018–), in which he evolves the lexicon of colonial-era casta painting—a genre that exoticized and dehumanized the peoples of New Spain (Mexico) by dividing them into racialized hierarchies—into a poignant and empowering form of representation. In Terrill’s contemporary take, sitters collaborate by thinking through their own racial, sexual, and gender identities, which are then inscribed along with their names directly onto each portrait. While there is an aspect of parody to these paintings, Terrill ultimately allows his subjects to assume the full dignity and complexity of their humanity.

Dominican-born artist Lizania Cruz destabilizes exclusionary and racialized practices and histories through investigative projects that engage the public. In a recent work titled ¡Se buscan testigos! (Looking for witnesses!) (2020–21), Cruz posed questions such as “What do you learn in school about Christopher Columbus that you consider is the true story?” and “Dominican, do you consider yourself Black or Indio, and did migrating change your perspective?” via signs and flyers disseminated to residents of both the Dominican Republic and Dominican diasporic communities in New York City. She compiled responses using an app she designed to create “an archive of the narratives that have been passed down throughout generations and are now unfortunately ingrained in how we (Dominicans) perceive our identity. I hope viewers understand with this work how violent the creation of the nation-state as an institution is, and how its apparatus excludes some from belonging.”8 More broadly, Cruz’s work invites the public to consider the implications of how we see ourselves, to inhabit multiple ways of belonging, and to reclaim our places within narratives that are not only multivalent but shifting.

I feel that keeping things minimal and making sure things have room to breathe is a very western white supremacist ideal, so I’m all about the baroque. Just fill it all up.

Justin Favela

Known for his ebullient large-scale installations, Las Vegas–based artist Justin Favela transforms predominantly white cultural spaces into safer, more welcoming and relatable environments for diverse audiences. “As a queer, fat, Latinx person in America, just existing and taking up space in institutions like art museums is really important in my practice. The symbolism of literally covering white walls with color is something that really informs my work. Also I feel that keeping things minimal and making sure things have room to breathe is a very western white supremacist ideal, so I’m all about the baroque. Just fill it all up.”9 Favela’s mesmerizing “piñatafied” environments, sculptures, and paintings are visually sumptuous, irreverent, and humorous. Upon entering one of his spaces, an immediate sense of warmth and celebration is relayed not just by his vibrant palettes, but by his use of craft materials and pop references. At the same time, his works proffer critical deconstructions of popular culture, Latinx stereotypes, and the romanticization/exoticization of Latin America. In Fridalandia (2017), an installation at the Denver Art Museum, Favela recreated Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul patio garden, as depicted in the 2002 film Frida, with materials traditionally used to make piñatas. Surrounding the garden were murals based on nineteenth-century Mexican academic landscape paintings, whose purpose was to convey favorable images of the nation to both locals and foreign audiences. By boldly reiterating these depictions—which many observers accept as authentic, factual references—Favela encourages the public to reexamine commonly held ideas regarding Mexico and Mexicanidad.

Chicago-based social practice artist Maria Gaspar utilizes architecture and public space to interrogate systems of power, with a particular focus on those that seek to erase or scrutinize brown, Black, and other marginalized people. Gaspar maintains that “No space is neutral. In contrast, it is ripe with ambiguity, subtlety, and complexity; therefore, working within a site-specific or site-responsive format compels me to deconstruct it in ways that I find meaningful and nuanced. I research, experiment, and identify methods that allow me to transgress space.”10 Gaspar’s long-term site-specific works—especially within and around Chicago’s Cook County Jail, located in the artist’s childhood neighborhood La Villita (Little Village)—call for intimate collaboration with incarcerated individuals and the communities surrounding them. With Radioactive: Stories from Beyond the Wall (2016–18), for example, she broadcast inmates’ stories and sound recordings, and projected their drawings on the exterior of the jail, conveying their experiences to audiences outside the prison’s boundaries. Just as Gaspar’s work deftly enables collaborators and participants to penetrate or surmount societal barriers, her practice itself pushes beyond the confines of activist art by allowing projects to evolve naturally over time in accordance with the needs of the particular communities she engages.

With these astonishing practices in mind, it seems impossible that—as Latinxs—we are still counting the public successes of Latinx artists, tallying art school graduates, prize winners, residencies, as well as Latinx absences within major exhibitions and collections. Reflecting on her hopes for the future of Latinx art, Gaspar ventured, “I want my two-year-old son to go to a major contemporary art museum and recognize the works of Latinx artists. I want to see him learn about Latinx artists across the curriculum; it should not be limited to Hispanic Heritage Month. I want to see our work normalized, theorized, written about, collected, and loved on. Look around, we are here, we’ve been here.”11

1Elia Alba, “Estamos Bien: Curator’s Conversation on El Museo’s La Trienal 20/21,” online panel discussion, El Museo del Barrio, New York, February 22, 2021.

2Arlene Dávila, Latinx Art: Artists, Markets, and Politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), p. 5.

3Glendalys Medina, in discussion with the author, August 11, 2021.

4John Rivas, in discussion with the author, August 9, 2021.

5Ibid.

6Rachelle Mozman Solano, in discussion with the author, August 4, 2021.

7Joey Terrill, in discussion with the author, August 11, 2021.

8Lizania Cruz, in discussion with the author, August 20, 2021.

9Justin Favela, in discussion with the author, August 17, 2021

10Maria Gaspar, in discussion with the author, August 12, 2021.

12Ibid.