Julian Rose is an architect and critic based in New York City. He is working on a book about museum architecture, Architects on the Art Museum, forthcoming from Princeton Architectural Press in 2024.

The letter begins with a burst of confidence: “Dear Donald Judd, A few weeks ago I did win an architectural competition for a new art museum.” But the tone quickly turns shy, deferential: “Reading your book Donald Judd Architektur and being inspired by your work for some time already, I dare asking you: Would you mind giving me an opinion (a criticism) on the project whenever you will come to Europe?” The museum in question was the Kunsthaus Bregenz and the invitation was extended by its designer, the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor.1 After the building opened, in 1997, it would garner widespread acclaim as one of the best new exhibition spaces in Europe, becoming a major stop on the international art circuit and helping to set up Zumthor for his eventual win of the Pritzker Prize in 2009. But all that was years away when he wrote this letter to Judd, in February 1990. Zumthor, at the age of forty-six, had a growing reputation but only a handful of built works, and was still regarded primarily as a regional architect. Judd, at the age of sixty-two, was one of the most prominent artists in the world and was particularly beloved in Zumthor’s homeland, where he had exhibited regularly since the early 1970s. Moreover, Judd was taken increasingly seriously as a maker of buildings as well as artworks. Donald Judd Architektur was the catalogue of an exhibition devoted to the artist’s architectural designs that was held in Münster in 1989. The show was greeted with fanfare in the European press, while the book quickly sold out a first print run, then another, and another.2 No wonder, then, at the earnest respect of Zumthor’s appeal.

Evidently the respect was mutual, and conversation evolved into collaboration. By the summer of the following year, a plan had been outlined: Judd would design a new building to house the museum’s offices, to be located across a small plaza from Zumthor’s structure. It seemed like a coup for everyone involved: Judd would have his first ground-up building in Europe, Zumthor would collaborate with one of his heroes, and the Kunsthaus, newly established to promote interchange between art and architecture, would gain a unique ensemble that perfectly embodied its interdisciplinary ambitions. As Edelbert Köb, the museum’s founding director, enthused to Judd that July, “I am naturally very happy about it . . . to begin with a building by Donald Judd would definitely be a wonderful start for our exhibition house.”3

Just a few months later, in October 1991, Zumthor wrote an irate letter to Köb. Whatever Judd contributed to the project, Zumthor fumed, he must keep in mind that the state had commissioned “me, as the architect,” to design the museum and all its facilities; the entire complex should therefore be shaped according to his creative vision. Scoffing at the idea that Judd would be able to “single-handedly realize a building on the museum site,” Zumthor suggested he remain involved in some other way, perhaps with a large-scale outdoor artwork in the museum plaza. After all, Zumthor said in closing, “that was what the artist Judd was meant to do. He should not be working as an architect for an administrative building.”4

From Donald Judd Architektur to Donald Judd “the artist” in just over a year and half—what happened? And what happened, also, to Judd’s design? Incredibly, even in the face of Zumthor’s opposition, Judd followed through on his end of the bargain: working for months, he produced numerous sketches, supervised construction of a detailed physical model, and even had a set of CAD drawings made by a young Swiss architect. If not quite shovel ready, these plans show a clearly articulated architectural vision, certainly as resolved as any number of influential paper-architecture projects from the same era. Why has its story never been told?

In retrospect, the answer to the first query seems inseparable from that to the second. Then as now, Judd’s project raises a confounding question: what does it mean for an artist to make architecture? Not to adorn or alter it, not to critique or consult on it—not to respond to architecture, in other words, but to produce it, realizing spaces and structures all of their own. This is a particularly fraught problem to pose in the context of a museum; at heart, it asks who should have the privilege of framing our encounters with works of art.

But it raises larger questions, too. If an artist succeeds in making architecture, does this affirm that architecture is on a par with art, an art form in itself? If the artist fails, does this bear out architects’ deepest fears that they are engaged in some lesser form of cultural production, at worst complicit, at best merely utilitarian? Conversely, does it not seem that artists must succeed in making architecture if they are ever to realize the cherished avant-garde dream of merging art and life? After all, what does it mean for art to break free of the museum’s walls, to enter the city or the landscape—to become public, collective, transformative—if not to become somehow architectural? Such questions are easier left unasked, for they force a reckoning with the agency of art and architecture alike—a confrontation with both their potentials and their limits. Yet that is precisely why they are worth addressing now, as so many efforts are underway to rethink the nature of the art museum, and while so many practitioners in both fields are reevaluating their roles not only in relation to each other but in society at large.

Understanding what happened with the Bregenz collaboration in the early ’90s—and grasping the significance of these events today—first requires recognizing an important shift in the evolution of Judd’s practice. While Judd had expressed interest in architecture from the beginning of his career, his initial forays into the field were undertaken, as he put it in a well-known essay in 1977, “in defense of my work.”5 They were rearguard actions, in other words, driven by his frustration with the ways in which museums and galleries typically installed and exhibited his art. But this fundamentally changed when Judd partnered with the Dia Art Foundation to create a new complex of exhibition spaces in Marfa, Texas, in the late ’70s. The project, initially called the Art Museum of the Pecos, would be more public facing than the hybrid living and working spaces that Judd had previously designed to house his art.6 Most important, Dia’s deep pockets allowed Judd to undertake art and architecture projects truly in parallel for the first time, designing new works simultaneously with the new spaces that would house them.

The most dramatic example of this novel working process unfolded in the buildings known as the Artillery Sheds, two vast, low-slung concrete boxes constructed in 1939 to provide storage space for a US Army fort then located on the outskirts of Marfa. From approximately 1979 to 1985, Judd renovated these structures to house the 100 untitled works in mill aluminum that he designed and fabricated over roughly the same period (1980–86). Partnering with regional architects and contractors, Judd undertook two transformational phases of work on these buildings. The first, from 1979 to 1981, was to design and install new windows and doors; the second, from 1982 to 1985, was to design and install new roofs.7

The motivation for the first move is practically self-evident: the original structures were dark and cavernous, and the flood of raking sunlight that Judd introduced by lining each long wall with massive windows was crucial to activating the reflective angularity of the aluminum works he wanted to install there. The roofs are harder to grasp. In published accounts, Judd explained that the existing roofs were leaking and needed replacement, but this functionalist alibi does not survive consideration. Technically speaking, Judd did not replace the defective roofs at all; he covered them over with enormous curved vaults of corrugated metal. It was a bizarre move, dramatically increasing the height of the structures without increasing their occupiable area—something like a three-dimensional version of the false storefronts in an old Western town.8 And because the project amounted to erecting a whole new building on top of an old one, it was costly. “A flat roof would be cheaper,” Judd allowed when making his case to Dia’s director in November 1982. But privately he was also willing to admit that his motivation was less practical than aesthetic: “The main argument against them is their price. The arguments for them are: the buildings would be beautiful.”9

You can’t exaggerate the importance of proportion. It could almost be the definition of art and architecture.

Donald Judd

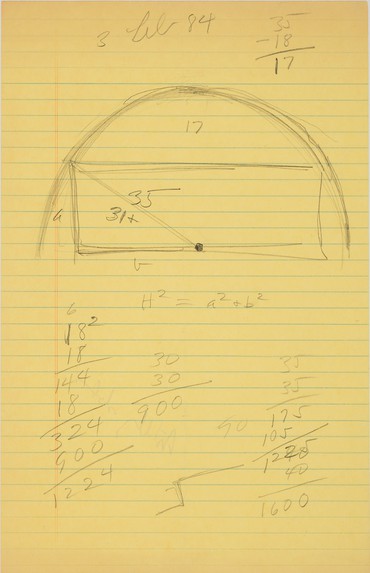

And Judd had a very particular vision of the beauty he wanted. The first construction company he approached proposed a gently curved arch some eight feet high, enough to drain effectively while economizing on material. Judd disliked these proportions and pushed back until the dimension had been increased all the way to eighteen feet, the same height as the existing buildings, to create a perfect 1:1 correspondence between new and old structures. He also became obsessed with the precise nature of the curve itself, studying different geometries until, as a Dia employee reported in a note to the contractor, “Don has decided that he wants the arc of the roofs to be the arc of a true circle.”10 Specifically, Judd wanted the arc of each roof to form part of a circle that was centered on ground level at the midpoint of the existing building. The curve of the new roof would thus be part of an implied semicircle that exactly circumscribed the rectangular front face of each shed. This schema, illustrated in one of Judd’s sketches from February 1984, unified both the old and the new structures within a single overarching geometric framework.

If this talk of corresponding proportions and harmonious geometry sounds surprisingly classical, that’s because it is. And if the classicism of Judd’s design for the Artillery Shed roofs has so far been overlooked, that is because corrugated-metal structures have strong links to industrial and vernacular architecture, especially in West Texas, where they are commonly used as agricultural buildings. Judd loved both the industrial and the vernacular, and these associations were undoubtedly part of the appeal the new roofs held for him.11 But his insistence on the semicircular barrel vault—perhaps the paradigmatic form of Renaissance architecture, signaling the definitive rejection of the pointed Gothic arch and a return to Roman models—emphasizes the underlying classical bent. Nor do we have to look hard to find the likely connection: while pursuing an MA in art history at Columbia University, Judd spent a full academic year, fall 1960–spring 1961, studying under Rudolf Wittkower, one of the twentieth century’s most eminent scholars of Renaissance architecture. This link has not yet been seriously examined in the scholarship on Judd’s work, at least partly because Judd himself seems to have tried to suppress it. In his later years, he was increasingly open about his admiration for classical precedents, but he seldom mentioned his old teacher.12 In a 1992 lecture, for example, he emphasized how much he felt he had learned from studying the buildings of the past, explaining, “What you learn from Brunelleschi is how good architecture can be.”13 Yet that same year he told an interviewer, “I taught myself to appreciate the architecture of Brunelleschi.”14

Judd’s notebooks from Wittkower’s classes tell a different story. By 1960, Wittkower had become famous as something of an evangelist for proportion, arguing for its importance not only in understanding the art and architecture of the past but in renewing the quality and coherence of present practice. He had even given a keynote address on the topic at the 1951 Milan Triennale—sharing the spotlight with Le Corbusier, no less—where he told the audience, “Many young artists and architects have been my pupils; and it has struck me time and again that this question of order is uppermost in their minds.”15 Judd had clearly become one of these pupils—as he said in a 1983 lecture, delivered while he was in the midst of redesigning the Artillery Sheds, “You can’t exaggerate the importance of proportion. It could almost be the definition of art and architecture.”16

But simply claiming Wittkower’s classes as some kind of “source” for Judd’s designs would be far less interesting than asking what Judd was able to do with the ideas he encountered there. And Wittkower’s novel ideas about the experiential aspects of proportion, in particular, seem to have had a transformative effect on Judd’s thinking about architecture. In a classic article of 1953, “Brunelleschi and ‘Proportion in Perspective,’” Wittkower set out to correct what he saw as a long-standing misconception: since the Baroque, the Renaissance interest in proportion had been viewed with condescension, dismissed as an idealist fixation on objective principles disconnected from subjective experience. This attitude was based on the obvious fact that buildings look different from different points of view, which surely signaled the inevitable distortion of any inner order. Yet Wittkower convincingly argued that Brunelleschi “regarded harmony and proportion in the elevations of his buildings and their changing perspective views as a single problem.”17 In fact, he had designed his buildings according to geometric principles derived from his theory of perspective—emphasizing bilateral symmetry, parallel lines, and regular spacing—to ensure that their inherent proportions would be comprehensible from any point of view, thus bridging the “gulf between absolute proportions and the changing appearance of a building.”18

Judd devoted pages of dense notes to this article, and a brief return to the Artillery Sheds shows why.19 In absolute terms, his schema of the circle and the rectangle had doubled the height of these buildings; but for visitors approaching from the entrance to the property, the increase appears much more dramatic. The path to the sheds advances diagonally over a short rise in the ground. Because the land on which the buildings are sited is otherwise so flat, this gentle fold in the terrain is enough to obscure all but the top few feet of the original structures—but the massive vaulted roofs are entirely in view, looming at an oblique, Parthenon-like, to reveal their full volume. It is only in the last few yards of the approach, as the visitor descends to the level of the ground at the building’s entrance, that the “true” proportions of the elevation come into view. This is obviously not a direct application of Brunelleschi’s principles, because Judd is not trying to enforce a coherent reading across differing viewpoints. Rather, he is exploring the ways in which movement through space can mediate between divergent, even contradictory readings of a structure, encouraging the viewer to focus sequentially on different sets of relationships, first extrinsic to the architecture—between body, landscape, and building—and then inherent to it, between the rectangle of the wall and the curved segment of the roof.

Similar plays unfold in the buildings’ interiors. The visitor’s visual field is dominated by two grids. Above is the shed’s muscular structure—a network of steel-reinforced concrete beams nearly a foot deep—which takes on a visual function akin to that of the coffered ceiling at Brunelleschi’s San Lorenzo, in Florence (one of Judd’s favorite buildings), breaking the vast interior space down into legible units that diminish in reassuringly regular intervals as they recede into the distance. Below is the precise array of Judd’s aluminum boxes: symmetrical, parallel, and equidistant. Judd based the dimensions of the artworks on the dimensions of the buildings, and at first glance the clear correspondence suggests that this grid, too, is some sort of perspectival visual aid, not unlike the parquet flooring that was a favorite device in Renaissance painting. But as the raking sunlight hits the unique geometry of each box—the different angles of the interior partitions, the different combinations of solid and void—this apparent parallelism explodes into a riot of contradiction: empty cavities cast in shadow read as opaque, inky solids; glossy surfaces disappear, as if erased by their own reflections. And just as outside, the movement of the visitor’s body itself mediates between these two dichotomous systems. Walk twenty or thirty feet into one of the Shed’s interiors, and the building’s structural grid will track your movement reassuringly—it is almost impossible to feel disoriented in the presence of such clear spatial coordinates. Yet that same trajectory will continually reshuffle the plays of light and geometry among the aluminum boxes, unleashing a dizzying kaleidoscope of visual effects. To move through the Artillery Sheds is to experience space as both objective and subjective, structured and contingent.

The relationship between the subjective and the objective has long been a thorny issue in interpreting Judd’s work. All his life he railed against what he called the “false dichotomies” of the rationalist tradition, among them not only subject/object but thought/feeling, body/mind, and form/content. But what has repeatedly puzzled critics is the fact that Judd seemed to maintain a genuine interest in both terms in such pairs, unlike many of his peers, who favored more radically transgressive approaches that used one to undermine the other—whether the absurd, antirationalist “systems” deployed by Sol LeWitt, the raw, antiformal materiality of Eva Hesse, or the vividly antiobjective spatial gambits of Richard Serra. Judd loved literally superficial effects of color and reflection; he also believed in the inherent value of a logical inner structure. He explored both the absolute truth of mathematical progressions and the contingency of embodied experience. This has sometimes been taken as a shortcoming on his part, a lack of consistency or even of sophistication. But the Artillery Sheds suggest that in architecture Judd found a heuristic that allowed him to work through such persistent binaries in a dialectical fashion; he realized that space could be shaped in a way that would mediate between subjective and objective, perspective and proportion, body and geometry. Here, even the final distinction between artwork and building is transcended.

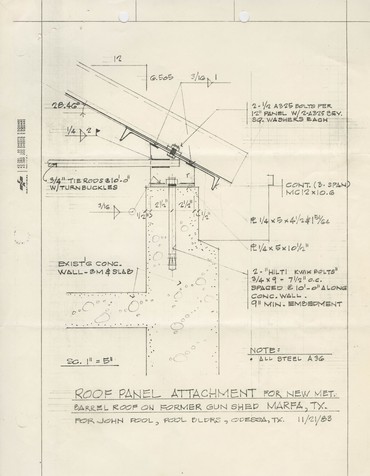

Yet differences between art and architecture do persist, sometimes in the starkest material terms. Measured against their most primordial function—keeping out the weather—the Artillery Shed roofs were an unmitigated disaster. The natural thing to do when knitting the two structures together would have been to have the new roof overhang the old so that it would shed water outward, and this was the arrangement proposed by both the first roofing contractor and the first architect Judd approached. But Judd was adamant that he wanted the corner where roof met wall to be completely flush—after all, this exact correspondence at the corner is the crux of their fusion into a harmonious whole. That seemed impossible (how would the roof be attached? Where would the water go?) and a series of architects and contractors refused to bid. One finally offered a compromise: nestling the new roof inside the existing parapet and tucking a concealed gutter in between.20

It looked plausible enough in the drawings Judd approved, but these were no fabrication drawings for an aluminum box; the material configuration they described was not a simple projection into space of the lines on the page. In reality, the junction between the undulating curve of the corrugated roof and the flat lip of the gutter’s flashing was a three-dimensional nightmare, almost impossible to seal. Worse, the design made no provision for the different rates of thermal expansion of the steel, concrete, and urethane foam that were connected at this joint. Hot days of desert sun, followed by near-freezing nights, created cycles of expansion and contraction that quickly tore open the seals around the new roofs. Within months they were leaking as badly as the old; it was obvious that the approach was fundamentally flawed. As a consultant hired to survey the damage put it, “I was surprised and appalled that anyone would design a roof system that would basically dump water inside an existing parapet wall.”21

For all its brilliance and dialectical power, Judd’s spatial practice also relied on certain untenable assumptions about space itself. If he recognized space as a means of overcoming difference—bridging gaps and contradictions, interlayering multiple ways of being or thinking and holding them together—it was because he saw space as a consistent, coherent medium. For Judd, space not only possessed a special unifying power but allowed the frictionless translation of ideas. The right spatial concept, in other words—a stack, a progression, a semicircular vault—could move fluidly from one material to another, even one place to another. This was largely true of his artworks, which evince ideas moving smoothly from wood to aluminum, plexiglass to galvanized iron, SoHo to Marfa. But at the scale and complexity of a building, heterogeneity is a fact of life, and a great deal of an architect’s labor involves accommodating difference, whether by designing expansion joints where two materials meet or creating a structural system that balances the distinct technical properties of constituent components like concrete and steel.

Even space takes on material qualities like temperature and humidity, sometimes with drastic consequences. An engineering study of the Artillery Sheds undertaken in 2015 to solve the problem of their still-leaking roofs also found that the 100 untitled works in mill aluminum had themselves been “creeping” around the interiors—some apparently moving several inches a year—because of diurnal cycles of expansion and contraction similar to those that have torn apart the roof. Their poised and permanent order is not immune to the material reality of the space they inhabit.22 This is the tension subtending the surreal collision between Judd, who tended to treat his buildings like artworks, and Zumthor, who had spent his career trying to make a new architecture inspired in part by Judd’s art.

(To be continued in the Fall 2022 issue.)

The author wishes to thank the many people who assisted in the preparation of this article, in particular Caitlin Murray and the staff at Judd Foundation for sharing their extensive knowledge of Judd’s practice and their help with navigating the artist’s archives; Hannah Marshall and Peter Stanley at the Chinati Foundation for their generous assistance with research related to the Artillery Sheds; Donna Cohen, Adrian Jolles, Thomas Kellein, Edelbert Köb, and Marianne Stockebrand for sharing their memories of working with Judd; the architect Leo Henke for his expert consultation on matters of architectural detailing and building fabrication; the artist Catherine Telford Keogh for her insights into Judd’s understanding of space; and Yve-Alain Bois for his incisive comments on the manuscript. The title of this article is drawn from Judd’s essay “21 February 1993,” in Donald Judd Writings, ed. Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (New York: Judd Foundation and David Zwirner Books, 2016), p. 881.

1Peter Zumthor, letter to Donald Judd, February 24, 1990. Bregenz Project Files, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas (JFA).

2Marianne Stockebrand, who curated the exhibition and edited the book, in conversation with the author, January 11, 2022.

3Edelbert Köb, letter to Judd, July 18, 1991. Bregenz Project Files, JFA.

4Zumthor, letter to Köb, October 23, 1991. Bregenz Project Files, JFA. Author’s translation.

5Judd, “Judd Foundation,” in Donald Judd Writings, p. 285.

6The name was changed to the Chinati Foundation, its current name, in 1986, as Judd and Dia parted ways. See Stockebrand, “The Journey to Marfa and the Pathway to Chinati,” in Stockebrand, ed., Chinati: The Vision of Donald Judd (Marfa, TX: Chinati Foundation/La Fundación Chinati, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 12–49.

7These chronologies are based on a comprehensive review of the records of the project retained in the archives of the Judd Foundation and the Chinati Foundation. From the surviving evidence, it is clear that by October 1979 Judd had solicited a proposal for new windows from Stockton Glass & Mirror, based in Fort Stockton. See “Proposal from Stockton Glass & Mirror,” October 8, 1979, Artillery Shed Project Files, JFA. He eventually selected a different contractor, The Glass House, Inc., El Paso, approving their final proposal in April 1981; the project was largely completed by that October. See Activity Reports 1981, Box 20, Folder II.1.3.3.002, the Dia Era Records, Chinati Foundation Archives (CFA). By the fall of 1982, Judd had begun soliciting proposals for the vaulted roofs from several regional construction companies, but the roofs were not finished until early 1985. See Artillery Sheds Correspondence, 1982, Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.003, and Suzan Campbell, letter to Naomi Newman, February 14, 1985, Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.006, both in the Donald Judd Records, CFA. For the 100 aluminum works I am relying on the chronology reconstructed by Stockebrand; Judd designed the first twenty-five works in April 1980 and the remaining seventy-five over the next four years. Because fabrication lagged behind design, the installation was not complete until the summer of 1986. (The works were produced by Lippincott Inc., in North Haven, Connecticut.) See Stockebrand, “Artillery Sheds with 100 Works in Mill Aluminum,” in Chinati: The Vision of Donald Judd, pp. 85–92. Any account of Judd’s architecture from this period should acknowledge the importance of Lauretta Vinciarelli, an architect and professor of architecture who was Judd’s romantic partner and occasional collaborator from the late 1970s to the late 1980s. Vinciarelli, as well her former student Claude Armstrong and Armstrong’s partner Donna Cohen, worked on various projects in Marfa, primarily at Judd’s residence. See, for example, Vinciarelli’s “Seven Courtyard Studies for Southwest Texas Courtyard Building for Donald Judd Installations,” Arts + Architecture 1, no. 2 (Winter 1981), pp. 36–37, on an ultimately unrealized exhibition building. Their involvement in the Dia project, however, seems to have been limited. Vinciarelli is mentioned only once in the correspondence on the Artillery Sheds, when a Dia administrator reports having discussed the idea of adding new roofs with her, Judd, and Armstrong in early November 1982, before design work had begun. See Willie Null, letter to Heiner Friedrich, November 3, 1982, Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.003, Donald Judd Records, CFA. It appears that Judd kept his work on his personal properties in Marfa largely separate from his work on the Dia project, and for the Artillery Sheds he employed architects and contractors who specialized in glass and roof construction. In conversation with the author on February 16, 2022, Cohen confirmed this impression, stating that she recalls no work on the Sheds by herself, Armstrong, or Vinciarelli. For a comprehensive account of Vinciarelli’s career see Rebecca Siefert, Into the Light: The Art and Architecture of Lauretta Vinciarelli (London: Lund Humphries, 2020).

8At one point Judd examined the possibility of installing a glass curtain wall at each end of the metal vaults, which would have made the space inside visible, but there is no evidence that he ever expressed interest in making the space under the vaults occupiable. The curtain-wall scheme was abandoned because of the engineering challenges involved.

9Judd, letter to Friedrich, November 2, 1982. Willie Null, Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.003, Donald Judd Records, CFA.

10Campbell, letter to Tom McClure, February 6, 1984. Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.005, Donald Judd Records, CFA.

11Writing about the redesigned sheds, for example, Judd compared them to an agricultural building in nearby Valentine, Texas, that he admired. See “Artillery Sheds,” in Donald Judd Architektur (Münster: Westfälischer Kunstverein, 1989), p. 74.

12Intentionally or not, Judd provided further misdirection by frequently acknowledging the influence of another famous professor, Meyer Schapiro, with whom he studied modern American painting. Presumably Judd was open about this connection because he liked to describe himself as heir to the American avant-garde figures whom he had studied with Schapiro, especially Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman.

13Judd, lecture at the University of Texas at Austin, March 9, 1992. Courtesy University of Texas Libraries at the University of Texas at Austin.

14Judd, in “Interview with Gunnar Jóhannes Árnason, Ingólfur Arnarsson, and Pétur Arason, July 1992,” in Donald Judd Interviews, ed. Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (New York: Judd Foundation/David Zwirner Books, 2019), p. 814.

15Rudolf Wittkower, “Appendix IV: Proportion in Art and Architecture: An Amalgamation of Previously Unpublished Lectures by Professor Wittkower,” in Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (London: Academy Editions, 1988), p. 145.

16The lecture, delivered at the Yale School of Architecture on September 20, 1983, appears as “Art and Architecture, 1983” in Donald Judd Writings, p. 348.

17Wittkower, “Brunelleschi and ‘Proportion in Perspective,’” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 16, no. 3/4 (1953), p. 276.

18Ibid., p. 280.

19In a sign of both how widely read Wittkower’s essay was and how applicable the theoretical problems it discusses seem to Judd’s work, Rosalind Krauss cited it in her early and influential text on Judd, “Allusion and Illusion in Donald Judd,” first published in Artforum in 1966. This connection does not seem to have attracted much attention because in the same essay Krauss cites Maurice Merleau-Ponty more extensively, and ultimately proposes phenomenology as a primary interpretive lens for Judd’s work. Phenomenology’s emphasis on the subjective over the objective, however, makes it an awkward fit for Judd’s work, as discussed below. See: Krauss, “Allusion and Illusion in Donald Judd,” in Annie Ochmanek and Alex Kitnick, eds., October Files: Donald Judd (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021), p. 11 n. 5.

20After securing Dia’s commitment to pay for the new roof over the summer of 1983, Judd approached the John Pool Corp., a construction company based in Odessa, as well as soliciting advice from the architect Robert Kirk, of Architectural Concrete Associates, based in Dallas, who was already consulting on the production of the large Works in Concrete located in the field beyond the Artillery Sheds. Both insisted on the overhang. Judd and Dia staff seem to have discussed the project with a number of other architects and contractors as well, but none were willing to design the roof without an overhang. As Campbell, a Dia curator based in Marfa, put it in a letter to Dia Director Friedrich in April 1984, “I have located only one regional contractor who I feel is both capable and willing to do the job.” This was Tom McClure of Target Industries, based in Midland. McClure collaborated with architect Bill Cox, a registered architect based in Lubbock, to produce the final construction drawings. See Campbell, letter to Friedrich, April 18, 1984. Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.005, Donald Judd Records, CFA.

21F. J. Hatfield, letter to Carl Ryan, November 22, 1985. Box 2, Folder I.1.1.1.4.006, Donald Judd Records, CFA. Dia briefly considered legal action against Target Industries and commissioned Hatfield and Associates, an El Paso architecture firm, to conduct an independent review.

22James Parker, “An Engineer’s Approach to Forecast the Long-Term Effects of Environmental Thermal Cycles on the Aluminum Works in the Artillery Sheds at the Chinati Foundation,” lecture delivered at the symposium “Mid-Century Modern Structures: Materials and Preservation,” organized by the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, St. Louis, August 26, 2015. See https://ncptt.nps.gov/blog/an-engineers-approach-to-forecast-the-long-term-effects-of-environmental-thermal-cycles-on-the-aluminum-works-in-the-artillery-sheds-at-the-chinati-foundation/ (accessed March 24, 2022).