Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

From 1943 to 1951, Francis Bacon leased a one-bedroom flat on the ground floor of 7 Cromwell Place, a large Victorian terraced house in South Kensington, London. For most of the 1860s and ’70s the house had been the home and studio of the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. Much later Bacon told David Sylvester, “When the war started and the bombs came, the whole of the roof of Millais’s studio had been blown in, and the room I painted in was never built as a studio. It was an enormous billiard room, like the Edwardians used to have at the backs of their houses. But it was a wonderful studio.”1 It was here that Bacon experienced a breakthrough in his art, painting a group of commanding, even shocking works including Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944, Tate) and Painting 1946 (1946), the first of the artist’s works to enter a museum collection when it was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1948.

Bacon shared the flat with Eric Hall, his patron and lover, a married man nearly twenty years his senior. His former nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, slept in the kitchen, helping him to organize illicit roulette parties during the London blackout. In the summer of 1946, with £200 in his pocket from the sale of Painting 1946 to the Hanover Gallery, Bacon moved to Monte Carlo with Hall and Lightfoot. For the next four years he would divide his time between Monte Carlo and London, with the occasional trip to Paris.

Among other attractions, Monte Carlo meant gambling, particularly roulette. As Bacon told Sylvester, “I became very obsessed by the casino and I spent whole days there—and there you could go in at ten o’clock in the morning and needn’t come out until about four o’clock the following morning—and at that time . . . I had very little money, and I did sometimes have very lucky wins.”2 Sylvester proposed an analogy between the artist’s gambling and his cultivation of chance or risk in his painting, eliciting the following response: “I think that accident, which I would call luck, is one of the most important and fertile aspects . . . because, if anything works for me, I feel it is nothing I have made myself, but something which chance has been able to give me.”3

I think that accident, which I would call luck, is one of the most important and fertile aspects . . .

Francis Bacon

In their recent biography of Bacon, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan paint a picture of his life on the Côte d’Azur as largely unproductive and ultimately depressing. Seduced by the Mediterranean climate, the good food, and the temptations of the casino, Bacon completed only a handful of paintings in Monaco, despite telling his friend Graham Sutherland that Monte Carlo was “very good for pictures falling ready made into the mind” and that “I paint dozens every week there.”4 One of the canvases he does seem to have finished, however, was a work that includes the very first representation of a papal figure in Bacon’s oeuvre. On October 19, 1946, he wrote to Duncan MacDonald, a director of the Lefevre Gallery in London, “I am working on three studies of Velasquez’s portrait of Innocent II [sic]. I have almost finished one. I find them exciting to do.”5 MacDonald had been the first to exhibit Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, in a group show in April 1945 that had also included works by Sutherland and Henry Moore. It was Sutherland who had recommended Bacon to MacDonald. A couple of months later, starved of the stimulating company of sympathetic fellow artists, Bacon wrote to Sutherland, hoping to persuade him and his wife Kathy to join him and Hall in Monte Carlo for the winter. “I don’t know how the copy of the Velasquez will turn out,” he added. “I have practically finished one I think. . . . it is thrilling to paint from a picture which really excites you.”6

An extensive literature exists on Bacon’s obsession with authority and father figures. In 1946 he would have known Velázquez’s full-length Portrait of Innocent X (1650, at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome) only in black-and-white reproduction. From 1947 on he could have seen the half-length version at Apsley House, London, when a selection of the Duke of Wellington’s collection went on show there, although the house itself did not fully open to the public until 1952. Head VI (1949) suggests that he may have known this smaller portrait too only in black-and-white reproduction, because he painted the pope’s cape purple (worn by bishops) rather than red (for cardinals and the pope). However, a number of Bacon’s radical 1950s reinterpretations of images of enthroned popes were based not on Velázquez’s portraits of Innocent X but on photographs of a living pope, Pius XII—a controversial pontiff owing to his alleged failure to publicly condemn Nazism and the Holocaust. In Bacon’s paintings he can be identified by, among other details, his metal-frame spectacles.

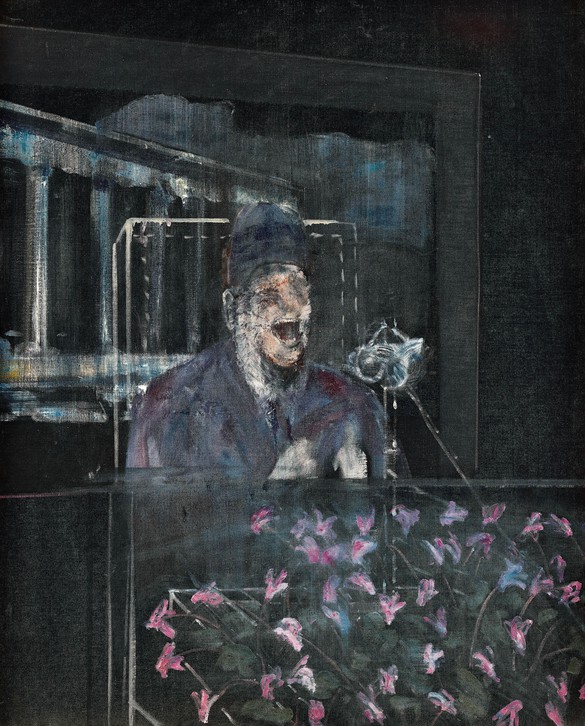

Mention of Nazism brings us to Bacon’s fascination with press and propaganda photos of fascist dictators and their henchmen. ‘Landscape with Pope/Dictator’ is one of a small number of paintings in which attributes of a Catholic clergyman—the biretta, or square cap, that the figure wears, for example—are combined with the secular garb of a political leader, such as a suit or uniform, shirt, and tie. The microphone, which has been called “that quintessential instrument of mass persuasion of the twentieth century,” appears in other works of this period, such as Study for Man with Microphones (c. 1946–48).7 Pius XII was the first pope to use the radio for mass communication. He was sometimes photographed speaking in front of microphones, although entirely without the atmosphere of suggestibility, hysteria, and violence implied by the shouting or screaming mouth and strutting stance of the dictator.

Questioned by Sylvester as to whether the open mouth in his paintings always denoted a scream, Bacon replied, “Most of them, but not all. You know how the mouth changes shape. I’ve always been very moved by the movements of the mouth and the shape of the mouth and teeth. People say that these have all sorts of sexual implications, and I was always very obsessed by the actual appearance of the mouth and teeth. . . . I like, you may say, the glitter and colour that comes from the mouth, and I’ve always hoped in a sense to be able to paint a mouth like Monet painted a sunset.”8 Elsewhere Bacon attributed his fixation with the mouth to “an old book . . . that had hand-coloured plates of different diseases of the mouth” that he had once found in Paris: “They always interested me and the colours were beautiful.”9

Bacon’s preference for painting on the reverse, or unprimed, side of the canvas originated during his stay in Monaco, when he was short of money to buy new canvases and simply turned round those he had already used. The back of ‘Landscape with Pope/Dictator’ is primed but Bacon chose to paint on the unprimed side, its rougher weave being more receptive to his techniques of painting the background with thinly diluted washes of color—almost like staining—and, conversely, applying impasto to the figure at certain crucial points. The architectural detail of vertical and horizontal lines coalesces into frames, columns, and a boxlike structure that predates the glass “cage” of later works such as Study for Portrait (1949). The columns appear to have been based on a photograph of a neoclassical colonnade, such as those found in buildings by Albert Speer and other Nazi architects. Speer’s “cathedral of light” spectacle, created by powerful searchlights for the closing ceremonies of the Nuremberg rallies of the mid-’30s, is echoed in Bacon’s Study after Velázquez (1950), in which an allover pattern of vertical gray and black stripes recalling the bars of a jail cell serves to isolate and imprison the figure.

The fusion of human and animal in the pope/dictator’s blurred face and wide-open mouth, with its prominent teeth, suggests that Bacon was already looking at photographs of monkeys and chimpanzees. Passages of blue and yellow paint, dragged or smoothed across the surface, and touches of white impasto vitalize the whole, while the predominant tonality of blue/violet anticipates the later series of popes from 1951 and 1953. Another arresting feature is the bank of delicately painted pink and green flowers, probably cyclamen, beneath the podium, evoking a crowd of waving or saluting hands. Pink cyclamen feature in the immediately preceding work in the Bacon catalogue raisonné, Landscape with Car (c. 1945–46), which in its earlier state also included an open mouth with bared teeth and a cluster of microphones.

In short, this is an important early work that disappeared from view for decades. Its descriptive title, ‘Landscape with Pope/Dictator’, is set in quotation marks in the Bacon catalogue raisonné because the artist did not give the picture a title.10 He must have brought it back to London when he left Monte Carlo in 1950. In 1951, he sold the lease of his Cromwell Place flat to the painter Robert Buhler, leaving it behind among some dozen canvases that Buhler either acquired or inherited. Years later Bacon told Sylvester, “I just had to get out of [Cromwell Place] because of many things—someone I was very fond of died there and I just didn’t want to stay there.”11 “Someone” was Jessie Lightfoot, who died at 7 Cromwell Place on April 30, 1950, aged eighty, with Bacon present. Her death affected him deeply.

1Francis Bacon, in David Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon (London: Thames and Hudson, 2016), p. 212.

2Ibid., p. 58.

3Ibid., p. 59.

4Bacon, quoted in Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, Francis Bacon: Revelations (London: William Collins, 2021), p. 241.

5Bacon, quoted in Martin Harrison, “Bacon in Monaco and France,” Francis Bacon: Monaco et la culture française (Monaco: Grimaldi Forum, 2016), p. 24.

6Bacon, quoted in Stevens and Swan, Revelations, p. 249.

7Margarita Cappock, Francis Bacon’s Studio (London: Merrell Publishers, 2005), p. 92.

8Bacon, in Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact, p. 57.

9Bacon, in Richard Francis and Ian Morrison, “Bacon on Triptychs, Technique, and Taking from Others,” 1985, in Francis Bacon: Couplings (London: Gagosian, 2019), p. 73.

10Martin Harrison, Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné (London: The Estate of Francis Bacon, 2016), pp. 2:46–05, 176.

11Bacon, in Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact, p. 212.