Mike Stinavage is a writer and waste specialist from Michigan. During his political science masters program at CUNY Graduate Center, he was awarded Fulbright and Martin Kriesberg fellowships to research the politics of waste in Northern Spain. He currently coordinates a European project on biowaste policy and writes fiction in Pamplona, Spain.

Contemplations of the status quo are prone to gross generalizations, woozy sentimentalism, or red-faced frustration—the latter being all too common. Weyes Blood evades all the above. In a powerful yet delicate testament to the times, Weyes Blood’s crafted melodies abstract the climate crisis and the onslaught of information. The low, sullen voice offers a kind of neo-folk, neo-Americana melody inlaid with serene austerity, thereby an alluringly vintage yet all too prescient soundscape. Perhaps that is why this California-born, Pennsylvania-raised musician doesn’t entirely identify with the genres of soft rock or indie rock ascribed to her. Imbibing the past, imbibing nostalgia, the honeyed tracks have a soft yet tenacious grip.

In a black half-zip sweater, Natalie Mering, the indie musician who performs as Weyes Blood, speaks from a Montreal hotel room from which, at one point, she shoos a staff member who mistakenly wanders in. Mering sits in a chair below a standard portrait of a suspension bridge, legs bent below and beside her, long hair falling across her shoulders. Despite being on the road, crisscrossing countries and states to play multiple shows in any given week, her expression is reserved and stoic.

During the first weeks of 2023, Weyes Blood’s “In Holy Flux” tour brought with it to Europe the new record And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow. The tour will continue around the world until November, when it’s set to close in the United Kingdom.

“I felt like people were really open to the vulnerability of the meaning of the album,” says the singer songwriter, referring to the first shows in Europe. And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow is internal and introspective. In the dark, cavelike environment that Weyes Blood summons by song, “The glow of your soul, of your humanity or whatever is left of it, would be the guiding force.” She has strong feelings about the idea of loss of soul, and of the dark night of the soul: “It’s been this very deep-seated loss of identity that leads to being at the bottom and not knowing how to get yourself out, to being helpless.” In Glasgow and Dublin this vulnerability hit a particular chord: “My music is very soothing and mid-tempo but people [in Glasgow] were really cheering and going crazy like it was a big rock show. I guess people were that excited about the meaning of the music.”

Mering’s previous record, Titanic Rising of 2018, brought critical acclaim. Though distinct from each other, the two records share not only the collaboration of Jonathan Rado of Foxygen but also a melodious dread belonging to a continued thought. “Titanic Rising is kind of sounding the alarm, a little bit of a warning signal. In the Darkness, Hearts Aglow is more of living amidst the blare of the alarm.” Mering equates the recent record to a postmodern plunge into “a subterranean river of Hades” in which one must confront the ghosts of intimacy and isolation.

This was not her first European tour. In earlier years she toured Europe multiple times, bringing the total number of tours to the teens. Those early shows, however, braved a youthful sense of abandon:

They were really scrappy. Just me with my instruments on a train with a Eurail pass, training to really small DIY shows across the continent and playing for like ten people. Because the shows are so much bigger now and the schedule is so much more demanding, there are moments where I give a little bit more than I have. When I was younger, I had unlimited resources. Now I have to be very measured about how much I give. It does take a lot out of you, versus going on stage and no one knowing who you are, and you’re just doing your own thing.

In sparse words, Mering speaks about René Magritte and French Symbolism. She mentions a pastel by Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Le Silence (1895), before pivoting to the work of Joseph Beuys, then the happenings of Fluxus, naming the Korean-American artist Nam June Paik. I look closely at the photo of Le Silence that appears in the video call’s chat box: a hooded figure against a starlit night presses two fingers in a V over their mouth. The haunting and dismal quality of the portrait confounds a gesture that in today’s lexicon is considered to be somewhat erotic. “For whatever reason,” she says, “it feels like my music.”

There is a hardness to Mering’s words, an assiduous formidability. She speaks slowly until something seems to catch her and sweep her forward. One such topic is the status of intimate relationships in the United States. “Everyday,” a song on Titanic Rising, poses the question, “Is this the end of all monogamy?” When I ask her how the question has weathered the past few years, she admits her embarrassment.

That was before the pandemic. I think nowadays monogamy came back in vogue because of the lockdown. In a place like America, I would say that monogamy has become more difficult based on the fact that everybody is in this endless cycle of illusion about reality. The pandemic kinda squashed that and made people a little bit more scared of being alone and unattached. I’ve noticed the pendulum swinging way more towards a conservative perspective where people really feel like they really missed out on marriage or childbearing after being fed some narrative about free love that isn’t actually possible.

Later she observes, “I don’t think nonmonogamy is something we’ve totally cracked. I’m a big fan of commitment and trust and I don’t know if everyone is built for polyamory. I think that that’s the myth.”

Mering links today’s buzz about nonmonogamy in part to the nihilistic way in which Gen Xers were raised. “They may have accidentally created this myth that everything structured is pointless.” This linkage, although grand, is not an accusation or a conclusion, but her attempt to make sense of the present. “I’ve been trying to pinpoint when marriage and childbearing became so painfully out of style.”

In the music video for “It’s Not Just Me, It’s Everybody,” Mering dances a duet with an animated and embittered smartphone on a stage of death and destruction. Recalling her nostalgia for times past, reported in The New Yorker and elsewhere, I ask if personal phones and digital culture, too, will go out of style. “I think that we were all kind of hoping for that, but I think that because everyone is addicted, it makes it less likely. I also notice that there’s no growing desire for privacy. If anything, there’s a growing desire for less privacy and more fully merging with the idea of yourself as a public persona.” Referring to social media, Mering says, “I see it as we haven’t cracked the code on what it’s done to us, and so how could we possibly crack the code on what to do with it. . . .We’re kind of attention harvesting each time we’re on there. It’s become a more treacherous place. It’s less of this fun utopian digital social idea than it was in the ’90s.”

Yearning for shared cultural movements or experiences, Mering laments the stark American individualism that undermines them. Despite this, with her clear vision, she prefers to maintain Weyes Blood as a one-woman band. That, however, does not preclude collaboration: “I’m down. But everyone is just so . . . ” —heavy silence—“busy. I find that people are genuinely kind of calculated in a way that’s not artistic.”

Mering isn’t the first American artist (and won’t be the last) to be enticed by Europe. On a visit to Italy last year, she found herself admiring the ease with which people socialized and the pride and gratification that arose through talking about quotidian activities. “In America, you’re just chiseling away at everyone’s impossible schedule and trying to squeeze in as much as you can. In a very hectic environment, there’s just not a lot of space created for the relaxed and open social engagement. But I still think there are places in the US where people are proud of where they’re from. They’re not moving to cities and talking about it. They’re staying where they are.”

The double punch that Mering packs in Titanic Rising and In the Darkness, Hearts Aglow is less a representation of American culture than an interrogation of it. There’s a melancholic, warping quality that seems to bend time, dashing her music into past decades. But as the style reverberates, the lyrics stand concretely in the present, thoughtfully crafted from an America entangled in a climate and digital-culture conundrum. And in her experimentation, she’s bypassing the noise to make rich and thoughtful melodies.

Toward the end of the interview, I ask Mering if she can recount a dream from the European tour. “Yeah,” she says with a tempered grin. “I had a really weird dream that I was eating glass. I was chewing on it, and I really wanted to rinse my mouth out, but I felt like I had to get rid of the box of glass shards first, so I was wandering around a garage looking for a recycling bin. My mouth was really hurting and when I put the glass down, I was like, ‘Huh, I should really go rinse this out.’ Then I woke up.”

“I think that was a dream about numbness,” she offers next. “I was coming out of my numbness. During the pandemic, not really being able to tour or play shows, I had become a bit numb to what I do. Doing the tour, I woke back up to the meaning and purpose of what I do because so much of it is that generative experience of seeing the songs unfold live. I love making records and recording but it’s very abstract. There’s something very immediate about playing a show.”

Just before recollecting the dream, she speculated, offering a glimpse into the future: “Maybe the third record in the trilogy would be more about redemption, kind of what happens after all of that. Rebirth and awakening.”

Perhaps there’s a third punch on its way.

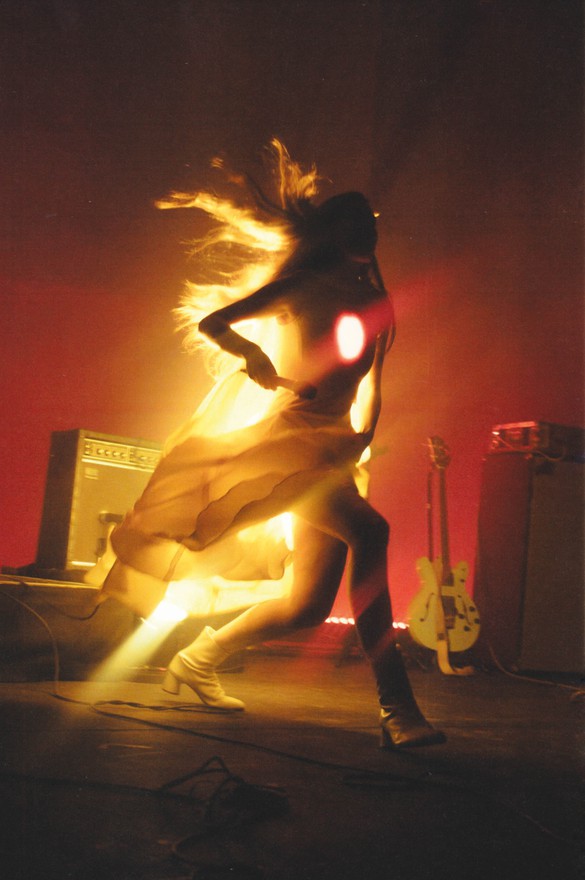

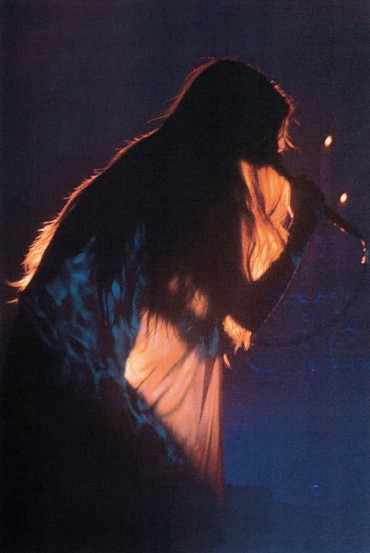

Photos: Neelam Khan Vela