After completing a BA at the Universität Basel, Yves Guignard defended a doctoral thesis in Lausanne on the German art dealer Wilhelm Uhde. He has worked as a translator from German into French and as a cultural mediator for the Fondation Beyeler, the Kunstmuseum Basel, the Fondation de l’Hermitage, and the Musée cantonal des beaux-arts, Lausanne.

Precocious Illustrator, Little-Known Draftsman

With a show of his paintings at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1956, Balthus set himself at the highest levels of modern art without the public knowing anything about his drawings. It was only in 1963, at the New York gallery of Eugene Victor Thaw—not Balthus’s main dealer, which was the Pierre Matisse Gallery—that his drawings were first exhibited, opening a whole new world for the public and especially for the critics. Balthus was fifty-five years old.

Surprisingly, critics and scholars, notably Jean Leymarie, have been fascinated by Balthus’s drawings insofar as they do not reflect or mirror his paintings.1 While the painting, seen as the “main” part of Balthus’s work, is celebrated for its modernity, his drawings have captivated instead through their classicism, which makes the artist timeless, swimming against the current, indefinable, eternal. There lies one of the contradictions of Balthus’s drawings, though not the only one. Another contradition is indeed his classicism, since the painter never attended any academy; he was completely self-taught, having been raised among artists.

Another curious fact is that, although Balthus devoted himself to painting as an adult, he was certainly the modern painter who enjoyed the success and widespread circulation of his drawings at the youngest age, while he was still a child. It is less common to speak of child prodigies in drawing than it is in music: either they don’t exist or they lack visibility. But Balthus’s mother, Baladine, was the muse to one of the greatest poets of her time, Rainer Maria Rilke, and he was fond of and admired her children and paid great attention to Balthus’s first drawings. At the age of eleven, the child, Baladine’s youngest son, executed a series of images in ink that depicted a personal misfortune: the disappearance of a small cat, with his owner searching for him everywhere in vain. A book with these drawings, Mitsou: Quarante Images par Balthusz, was published in 1921 (by Rotapfel Verlag, of Zurich and Leipzig) and included a preface by Rilke. The print run is unknown but the book’s distribution and visibility were considerable, especially for a twelve-year-old child.

Some might remark that because these works were intended to be printed, they should be considered illustrations rather than drawings. In this regard, before entering further into the world of Balthus’s drawings, we should mention another series he created to be printed, a group of illustrations of 1933–34 for Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847). Balthus was not someone scattered in his interests; he had fascinations and radical passions to which he devoted himself. In painting it was Piero della Francesca; in music, Mozart; in literature, Emily Brontë. The same exclusivity manifested in his travels: he spent some of his childhood in Berlin, served in the military in Morocco, traveled to England for an exhibition, and in 1962 visited Japan, where he met his future wife, Setsuko, but otherwise his life unfolded in France, Switzerland, and Italy, as if the rest of the world did not exist. His admiration for Brontë prompted an exception, a few short visits to London in around 1936 to work on exhibiting the series inspired by her in her own country.

The Brontë series includes the only works on paper that Balthus showed in exhibition before he was fifty-five. They barely represent the classicism that critics would speak of later: they’re expressive, modern, sometimes harsh; the proportions of the figures are slightly caricatured; the hatching, while skillful and rhythmic, is free and wild. These are ink drawings and lack the nuance made possible by graphite and charcoal.

The Myth of Disdain and the Confidential Production

The art historians John Rewald and James Thrall Soby helped perpetuate a myth that Balthus belittled drawing and focused only on painting. Rewald wrote, “He was at pains to satisfy my wish to see his drawings. A number of them were strewn on the floor where they had been walked over to such an extent that they were no longer presentable. . . . Most of his drawings are preparatory studies for compositions, working sheets, so to speak, in which he loses interest as soon as they have been transposed to paintings.”2 And Soby, curator of the MoMA show in 1956, quotes him, “When I have finished my paintings, I put the drawings for them on the floor and walk on them until they are erased.”3 But we must be careful. Is this really true? Even if it is, many researchers later learned to be wary of Balthus’s statements. In any case, the artist was photographed by Loomis Dean in 1956 for Life magazine, and there is not a single piece of paper in those photographs, not even on his studio table.

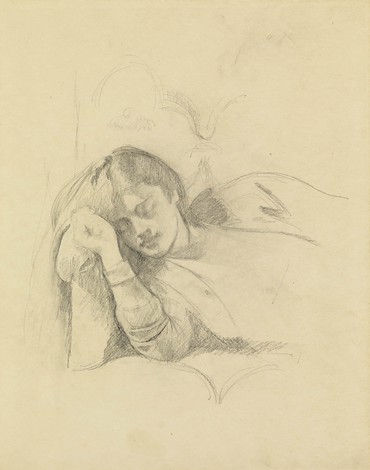

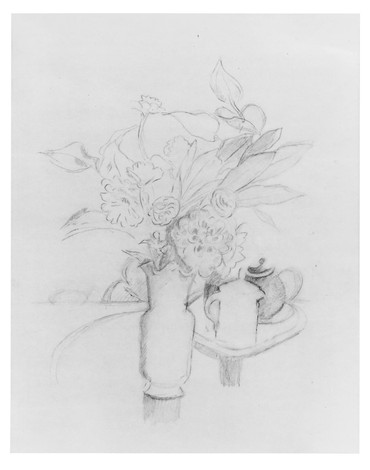

Nevertheless, to declare that Balthus disliked drawing is mostly untrue, although there were certainly drawings he destroyed. The catalogue raisonné clearly documents that he practiced drawing regularly from his early years on. The great majority of his drawings are studies for compositions, means to an end. With significant talent and authority, Balthus sought the best posture for his models—whether it was the position of a leg, the tilt of a head, or the direction of light, he was constantly searching. Such drawings are literally studies, but sometimes a drawing goes well beyond a study, with the artist demonstrating the utmost care: the pencil line caresses the paper in subtle shadows, and it is as if the figure—or tree, or still life—emerges from the flatness of the paper, as if it had been carved. In this way Balthus brings form out of the whiteness of the paper like a sculptor giving life to marble, employing the same stroking gestures, and the grace of the image that appears seems to have always been there.

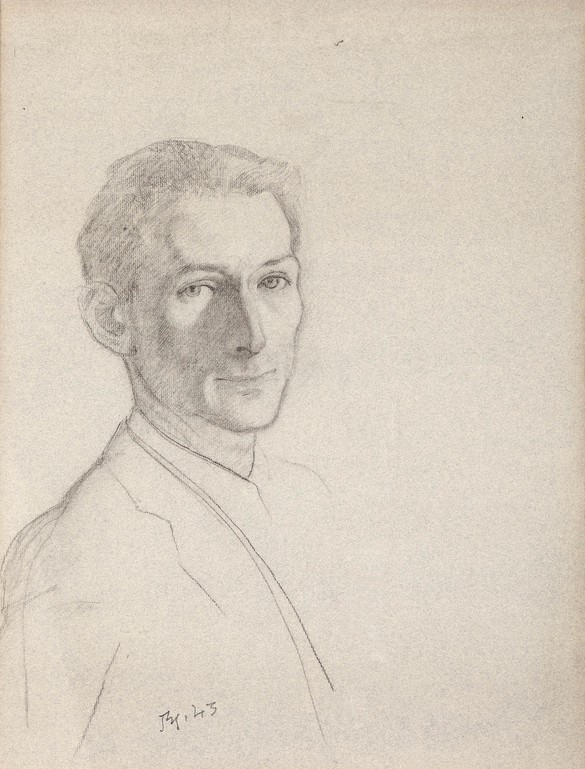

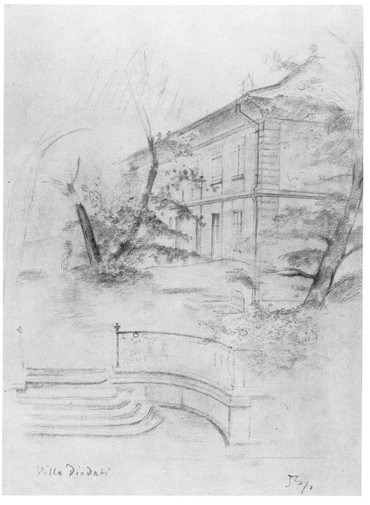

When did Balthus decide to make drawings as works in and of themselves—drawings intended to be framed and hung, or at least stored in a portfolio? Relatively late, but well before 1963. Format is a clue to identifying these works: when the drawing is large, very much finished, and not associated with a known painting, it is a “pure drawing,” the intention of which is the beauty of the line and the final representation. It is no longer a means to an end but is its own purpose. The first documented drawing of this kind is La Villa Diodati of 1946. Here, it is interesting to consider the context: Balthus had recently married an aristocrat, was the young father of two sons, and was renting a beautiful home not far from Geneva. One might enjoy seeing this work as the beginning of a “return to order,” similar to what Pablo Picasso experienced between 1915 and 1925, after his first marriage. Balthus’s most refined and noble self-portraits also emerge from this period, small in size but perfectly complete.

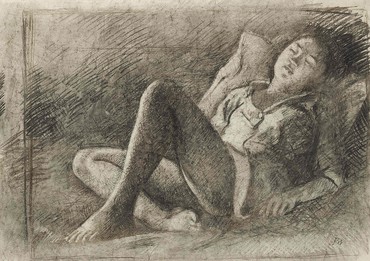

Balthus quickly turned away from bourgeois life, however, and less than a year later returned to the solitude of his uncomfortable studio/apartment in Paris. His next drawings in the vein of La Villa Diodati were portraits of his mistress and muse at the time, Laurence Bataille. While there are two or three painted portraits of Bataille, several drawings present attitudes—a singular tilt of the head, even bare breasts—that do not appear in the oils. They can therefore be considered finished, autonomous pieces parallel to the paintings.

Balthus then discovered Burgundy, where he first rented and then bought a medieval château in Chassy, living there from 1954 to 1960. He first shared the château with Léna Leclercq, a poet who served as a housekeeper, and then with a new muse and mistress, Frédérique Tison. His portraits of Tison include beautiful, incredibly pure drawings like those of Bataille. They attest to a fascinating encounter, a game of hide and seek between shadow and light. Certain larger works on paper are watercolor studies for known paintings, for example the well-known views of Tison seen from behind at a window. In those cases Balthus executed drawings while painting, drawings that are more like variations, or alternatives, than studies.

The Drawing Exists in and of Itself and Photography Comes into the Mix

The next major stage in Balthus’s life began in Rome in 1961, when André Malraux, the French minister of culture, appointed him director of the Villa Médicis, Académie de France. Staying there over fifteen years, Balthus became passionate about the old Renaissance building, concerned not just with renovating it but also with restoring it to what it once was. That cause even took precedence over his painting: an artist whose production was already slow, he would realize very few canvases during this period. Drawing, however, would gain in importance.

Balthus drew a lot during his time in Rome and followed the market trends that emerged after his gallery exhibitions of drawings began in 1963. Some fifteen paintings at most, but hundreds of drawings, can be counted from his Roman period. A few years after his first drawings show in New York, the phenomenon won over Paris: in 1966, in conjunction with an exhibition of his paintings at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, the Galerie Janine Hao held an exhibition of his drawings. Five years later the Galerie Claude Bernard followed suit.

Balthus’s son Stanislas took note of this new market and of its relation to the artist’s financial needs in terms of his wish to restore the Villa Médicis to its former glory, both in its decor and as a site for receptions: “He began drawing frenetically because it was the only thing he could do quickly enough. . . . the drawings had been sold to Claude Bernard, and the funds weren’t for Balthus but for the Villa Médicis. However, the proceeds from the sale of these drawings were used to cover the costs of representations and a way to make up for a lack of financial means . . . to receive people properly.”4

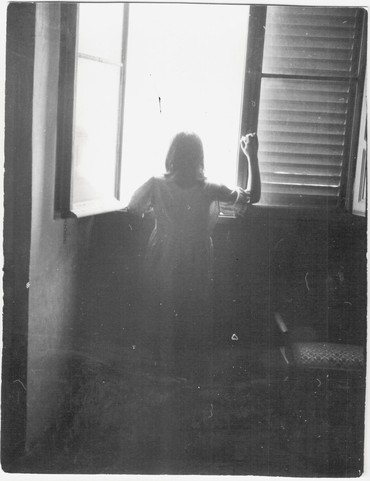

The best-known large drawings from this period are those dedicated to Balthus’s two favorite models, Katia and Michelina Terreri, the daughters of an employee at the Villa Médicis. Remarkably, during the sessions in which the young girls posed for Balthus, a collaborator and boarder at the Villa, Brigitte Courme, took photographs, leaving us a few rare images of the artist at work, or posing for the photographer. Balthus had a complex and long-lasting relationship with photography.5 There are photographs of his models dating from the 1940s, of landscapes such as the Gottéron valley, Switzerland, and of groups of figures, such as the series of three sisters executed over the course of the 1940s and 1950s.

Finally, the Roman period was notably when Balthus began using elephant hide paper, a kind of marbled paper that resembles parchment and gives the false impression of a rough surface. Yet the surface of this precious paper is actually very smooth, allowing Balthus to develop infinite nuances and gradations in Conté pencil or graphite. This dimension of more “precious” paper gives rise to new questions.

Posing Sessions . . . Posing Problems

The full complexity of this area of Balthus’s work is demonstrated in a series of drawings in which the artist sought to resolve a composition of several figures, one that never culminated in a painting. He drew the model during live sittings in his studio and sometimes worked from photographs taken during these sessions. There was no plan; photographs were not an indispensable part of the process but often accompanied it, like a parallel path, and were sometimes used for inspiration later.

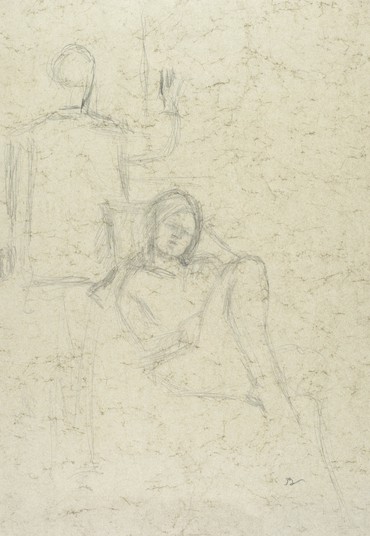

It is almost certain that when Balthus envisioned this composition, he combined sketches and drawings from different modeling sessions and photographs. Accordingly, a recurrent title for this group in the catalogue raisonné is “La séance de pose” (Posing session), as if that designated a painting project that never saw the light of day. The series focuses on a model lying on the back of an armchair with her leg bent. Sometimes the artist paints her standing up, bent over a table; sometimes another figure, who seems to be the painter himself, turns away from the scene and looks out a window.6

The series La séance de pose comprises works on fine elephant hide paper. There are other, equally refined drawings from notebooks that the catalogue raisonné describes as “studies for La séance de pose.” Why is one a study and the other not? If a drawing is from a notebook, is it then a study? Does elephant hide paper automatically indicate a larger intention? Clearly this distinction does not apply in every case, since certain drawings can belong to both categories, no matter what the support.7

We have but touched on such issues as a way to demonstrate the need for an in-depth reconsideration of Balthus’s catalogue raisonné for the purpose of revising it, as is the family’s wish, with the support of Gagosian. Besides the fact that many new drawings have been authenticated since that book’s publication, in 1999, the revision will reinterpret Balthus’s practice in the light of discoveries that have been made since then, preserved in the artist’s archives. To be continued.

1Jean Leymarie, an art historian, wrote on this theme several times, the first occasion being a catalogue published by the Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, in 1971.

2John Rewald, Balthus Drawings, exh. cat. (New York: E. V. Thaw & Co.), 1963.

3James Thrall Soby, Balthus, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1956).

4Stanislas Klossowski de Rola, during “Balthus: Les Décors Peints,” on the first study day of the conference “Balthus à la Villa Médicis,” Villa Médicis, Rome, 2013.

5The first to consider this question was Jean Clair in his article “Balthus photographe,” Connaissance des Arts 586 (September 2001). Recently, in 2021, Colette Morel defended her thesis on this subject at the Sorbonne.

6This although photographs show that Balthus made his model pose in this position at the window.

7Several ideas at the root of this article emerged from the exhibition of drawings from the Fonds Balthus at the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, in 2023, and from conversations with its curator, Camille Lévêque-Claudet.

Balthus artwork © Balthus