Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

“It’s about time we brought back the rom-com.”

“The what?” demanded one of my students, for whom English is a third language.

“Romantic! Comedy!” I answered, with a tinge of shame. I’d fallen into the classic trap: needless, buzzy belittling of perhaps the last sacred film tradition we have left. “Rom-com”—oh, ugly in its very sound, like a sinister piece of foreign policy from the Reagan years. No!

Start again: it’s about time we brought back the romantic comedy. It’s what I think we need more of in movies:

A) the romantic. That is to say, uplift, levity, but a serious levity, bubbles where you can hear the cork pop, commitment to this here-today-here-tomorrow? thing called love—which can be more than just a sexual relationship between at least two people.

B) the comic. That is to say, the anarchy of the guffaw, which relieves tension at the same time that it stokes it. In a world deluged by bitter/dumb irony, you gotta make ’em laugh, reel ’em in, and inject ’em with (gasp) sincerity and (here we go) taste.

What goes into a romantic comedy? Billy Mernit, who teaches UCLA students how to write the foolproof Hollywood rom-com, says it follows, without fail, a meet-lose-get formula: girl and boy (and he assumes the norm is girl-and-boy, and white at that, given that he lists “ethnic” and “gay” as rom-com subgenres) have “significant encounters,” girl and boy separate, and girl and boy reunite.1 Yawn! For one, you don’t even have to meet to fall in love: just check your DMs on Instagram from randos all over the world. Too neat for our purposes.

Mernit concludes that people watch rom-coms “to have their feelings—to experience the full range of emotions we all carry inside of us and the cathartic effect of letting such feelings loose,” that is, to “feel what it’s like to love and be loved . . . without being embarrassed,” to “give free reign to [our] sappiest, gooiest, most exalted expressions of love,” and “to believe in love and its transforming power.”2 Double, triple, quadruple yawn: the treacle drips too thick. Yes, our culture needs love stories. We need lift and levity, we need to feel something deep and holy, and love at its highest is the much-vaunted answer. But not as sap or sentimental bosh, not as an unswerving belief in an eternal maxim; I say: embarrass me! Make me guilty that I’m caught—again—in that vulgar web of passions and attachments. Yes, embarrass: after all, the French word for “kiss” is “embrasse.”

The classical practitioners of the romance-comedy film (Stanley Cavell identifies Leo McCarey and Frank Capra by way of William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson; I identify Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder by way of Miklós László and Oscar Wilde) have a half-phlegmatic, half-bloodthirsty side.3 In their pictures, falling in love is not an excuse for lightweight enchantment. It’s a ruthless battle of wits. Stubbornness—not a wistful, clean, sigh-filled “oh-why-aren’t-they-together”-ness—is the overwhelming tone. A showdown of egos, observed either with the detached old-world bemusement of a retired court jester (McCarey, Lubitsch) or the sadistic mania of the new one (early-to-middle-period Wilder, all of Blake Edwards). There are stakes to what they do that go beyond strings of gags or buoyant laughs. Our problem: we have defiled, through frivolity and irony, the romantic comedy, defanging the romance and flattening the comedy.

Take no prisoners in love—which, 99 percent of the time, we’d do better to call “desire,” “lust,” “the drives.” Utter selflessness goes into love, yes, but oh how often it backfires. Show that; be honest. Dating apps and social media have made partner choices as banal as an Amazon Go cart of bananas. How sad.

Okay: we’ll bring back the romantic comedy. Here’s our next problem: fresh ideas. The new watcher or filmmaker must have a syllabus that crackles, one highlighting movies that are honest about the mess and morbidity and clumsy repugnance of desire, yet one that doesn’t shy away from those stray rare miracles of life: elegance, economy, grace. Dissuade the blanket nihilist: there’s enough of that for the terminally online. It’s not enough to have been in love. It’s not enough to have seen When Harry Met Sally . . . (1989), fun and fine as it is. Knowledge should expand. Go back into cinema’s history: it’s not that long, it’s only a hundred years and change. As the Ronettes sang, it’s so young. So dredge up the forgotten, the decontextualized, and the unheralded.

The following list is an attempt at that. Mernit’s canon of rom-coms prizes box office above all—Pretty Woman (1990), Sleepless in Seattle (1993), There’s Something about Mary (1998)—while the American Film Institute list appeals to an unsurprising nostalgia, as in Roman Holiday (1953) and Annie Hall (1977). Masterpieces, but we know them already. My list is more idiosyncratic, and pushes the boundary of what we consider a rom-com. It’s certainly edgier than your classic Nora Ephron fare. My only requirements: there must be romance, there must be comedy, the balance between levity and gravity is heavenly, love must be taken seriously . . . enough to be either vanquished or elevated to the highest possible plane of human existence. C’est comme ça. The drawbacks: too many heterosexual couplings, too many white couplings, not enough films have been made about the zany romance that constitutes friendships.4 It’s the structure of the films, their themes and strange vibes and the larger-than-life people within them, that matter to me.

The 1930s and ’40s: Ernst Lubitsch

No education in the arts of either “rom” or “com” would be complete without Ernst Lubitsch, the German-Jewish émigré who took over Hollywood and changed the rom-com playbook. Anyone who wants to make a romantic comedy must have sophistication and Lubitsch is the source. His silent films should be studied for not only their grasp of the potential of a new art form (the motion picture) but also their crucial principle for getting around the whole no-talking thing: less is more. Show (or symbolize), don’t tell (or proselytize). When Hollywood embraced sound in the 1920s, many directors used it as a mere supplemental crutch, falling into the hoariest clichés: leaden dialogue, a dullard’s lack of imagination in moving the camera. But not Ernst. If anything, sound made him more elusive, more enamored with whispers, with rerouting the disruptive force of the erotic into flirting lines and visuals of sumptuous tact: shimmering moonlight on river water, lovers’ shadows draped across the sheets, sword and stocking kept neatly crossed at the foot of the bedroom. To paraphrase Billy Wilder, Lubitsch’s biggest acolyte, Lubitsch added two and two and made you come up with four yourself.

It is unwise and impossible to single out one essential Lubitsch film5 but one in particular cuts to the peculiar modern confusions of promiscuity and the libidinal abundance of choice: 1933’s Design for Living, starring Miriam Hopkins, Fredric March, Gary Cooper, and based on the dazzlingly randy Noël Coward play. Miriam cannot decide between struggling playwright Fred and unrepped painter Gary; she likes both. Conclusion: date both. “A gentlemen’s agreement . . . but no sex!” Further conclusion, according to the dream team of Coward and Lubitsch: throuples work. But to see how they make it work is a wonder of the cinema of comedy romance. In Lubitsch’s sound-era masterpieces, from Monte Carlo (1930) to Cluny Brown (1946), relations are messy, delayed, overlapped, in a perpetual state of collapse due to staid habit or overstimulation. But in the triangular machinations of Design for Living, they reach—with the destabilizing logic of dreams—the much-longed-for illusion of balance.

Late Billy Wilder

“Kiss Me, Stupid.” These three words give us Wilder’s sweeping view of humanity—and it’s a wise one: “kiss me” with all the love you’ve got, but don’t forget that you’re “stupid.” Wilder is my ideal of both grace and jadedness, sweetly realist (or is he really sweet?). He always wanted to be Lubitsch but was poised with more acidity: Lubitsch could never have made something as deliciously scummy as Ace in the Hole (1951) or Double Indemnity (1944). Yet Wilder got those out of his system early and ended his career almost exclusively making romance comedies, his true bread and butter.

Yet just as Wilder could never make something as unashamedly heart-on-sleeve as The Shop around the Corner (1940), Lubitsch could never have gone so far into the muck of the garish US bourgeoisie as Wilder’s Kiss Me, Stupid (1964), a cynical takedown of marriage whose sunny view on the unheralded glories of adultery is marvelously cockeyed. (Spoiler alert: adultery works sometimes.) And Lubitsch never showed the Proustian Sturm und Drang of desire quite as Wilder shows it in Irma la Douce (1963), a successful merge of the Shakespearean comedy of tangled identities and the violent jealousies of Swann in Love and The Sweet Cheat Gone, set and partly shot in a Paris where the prostitutes speak in Brooklyn accents. Irma came out in 1963, the same year as Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, and the two films pose similar questions of the cultural moment (what is a marriage? what is a relation between two people?), pairing off with each other well. And Irma la Douce was a favorite of Godard’s, who named it one of the ten best films of 1963. A marriage forms in one film, collapses in the other, but the same inability to communicate, the same untogetherness, wails in the saturation of Wilder’s Technicolor and the vacant horizontal spaces of Godard’s CinemaScope.

If there’s one film where Lubitsch’s European elegance and decadence emerge, phoenix style, from the ashes of the past, it’s Wilder’s Avanti! (1972), shot on the Italian island of Ischia. Juliet Mills is a poor woman unsure about her body (she’s disgustingly called “fat” and “fat-ass” by every man in the film), while Jack Lemmon is a rich man too sure about his own—one of those fat-cat industrialist Americans, chummy with Henry Kissinger and Spiro Agnew. Both their hang-ups disintegrate over a magical weekend in Ischia where they’ve gone to pick up the corpses of their respective parents: his businessman dad and her manicurist mom were having a steamy affair, egged on by the employees at the beautiful seaside hotel where they did the deed for the past ten summers. Son and daughter soon start an affair of their own, mixing the ghost of Freud with the insouciant buoyancy of that other lovely Wilde. Wilder didn’t like Avanti! much himself because “it stank of Italy,” and he preferred, like Lubitsch, the Paris of Paramount over the Paris of France. But we need not share his preference. I love the open air, the smell of Italy, and the slow-burn love on display in Avanti! I have seen Avanti! ten times. I plan to see it ten more. Its allure, its charm, are limitless.

Kiss Me, Stupid, Irma la Douce, and Avanti! were coscripted by the dream team of Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond, with whom the director worked on all his comedy films from Love in the Afternoon (1957) to Buddy Buddy (1981). To summarize a Wilder/Diamond script is a hopeless effort, for they spin labyrinthine plots that you must experience for yourself in real time. They stand on their own as literature.

Elaine May’s The Heartbreak Kid (1972)

Take the piss out of men: that’s the Elaine May way. But also take the piss out of women. Look at these dumb little lovers with their dumb little rituals of courtship. Look through a detached eye. Look as if you were at a zoo. But the zoo is a Miami Beach hotel, it’s a wedding, it’s a diner, it’s a class with that cute girl you see each day in passing, it’s a snug cabin in the woods: it’s anywhere where desire crouches, lying in wait to pounce on unsuspecting dreamers. It’s anywhere a sentiment is allowed to bloom. Stamp it out, cries May. Look, assholes, look!

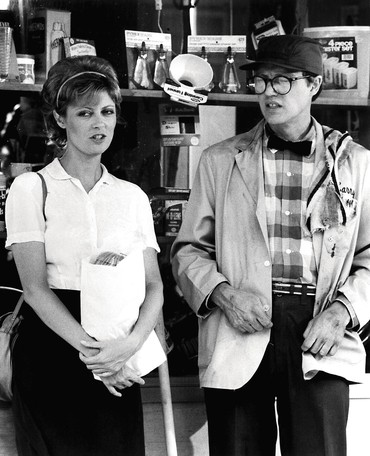

For all the disenchanted, this is the one. And who has not been disenchanted, at least for five minutes? And five minutes is all it takes for Lenny (Charles Grodin) to fall out of love with his new Jewish bride, Lila (Jeannie Berlin, daughter of Elaine). And five seconds is all it takes for Lenny to fall in lust with the shiksa blonde she-devil of his dreams, leggy freshman Kelly (Cybill Shepherd).

No one is safe from May’s withering eye. And it’s a cruel eye: she observes her scenes in long takes, letting the newlywed’s marriage proposal to the shiksa’s WASP-y parents play out in an unbroken five-minute take, letting the “I want a divorce on our honeymoon” conversation between Lenny and Lila run an excruciating ten minutes, interrupted by the farcical arrival of an elusive pecan pie. The inhuman speed of the drives becomes May’s subject: we see love deflated in real time. And good riddance, says May! No one knows what it is anyway. So you don’t deserve it. Harsh, but true.

The basic cornball premise is a frivolous Neil Simon joke, but it’s extended by May’s realism and timing, her bemused and detached yet never uninvolved contemplation of losers in love. She shares a grimness with my other favorite American comedian of the era, Jerry Lewis: those long, long takes stick with her unappealing characters until the bitter end. Thus we see revealed the whole gamut of society. Safety is not an option: no oasis. Everyone is obnoxious and grueling. Which Screenwriting 101 professor said you need likable leads? Ptui! You can have total SOBs and it still works. The SOBs need only be funny.

Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire (1977)

Luis Buñuel’s final film—a rom-com?

A rich Spanish sexagenarian (Fernando Rey) regales a train car of passengers—little men, tall women, children—with the story of his disastrous love affair with a tempestuous nineteen-year-old maid, Conchita. The hook: every time the Spaniard gets close to sealing the deal with his virginal objet du désir, the actress who plays Conchita steps out of the room and is replaced by a new, different woman who is still playing Conchita.

Buñuel claimed that there was no logic for when and why one Conchita was replaced by the other. Ha! The classic prattle of an auteur. Carole Bouquet plays Conchita as “Gallic”—vaguely, cool, frigid, husky-voiced. When Buñuel wants a Conchita who signifies (crudely) passion, fire, rockiness, the vulgarly “Spanish,” he sends in the flamenco-dancing Angela Molina. The hapless man is none the wiser: he cannot see, though we do, that Conchita is not a singular being, but rather two warring currents: attractive and repulsive, potential and kinetic, forward and back.

The man, too, is a split being. Though played physically by Rey (a stalwart of the Buñuel ensemble), Rey’s French was so thick that his voice was overdubbed by an uncredited Michel Piccoli. So body and voice are misaligned. No smooth wholes exist in Buñuel’s riveting deflation of the male libido, of reality itself. I take that back: of what is confused with reality. It’s high time That Obscure Object of Desire was admitted into the snug rom-com canon, since yes, the lovers win each other’s hearts in the end, and it leaves you singing the pleasure of life—by reminding you of the hell of the thought of flesh, not even the real thing.

Jonathan Demme’s Who Am I is Time (1982)

What moves me to romantic tears? I admit: the tears produced by most of the films on this list veer at times too close to the reptilian sardonic. Love, it’s clear, is a silly state; it’s far more cinematically fun—more spiritually honest, too; but perhaps easier—to see it fail than to witness it errantly and irrationally triumph, as we see in the Lubitsch/Wilder canon. Yet there are times that demand tendresse.

Which is supplied by the films of Jonathan Demme, but he adds a crucial adjective: kooky tendresse. Demme understood that life is nothing without kook, getting off on it in films like Citizens Band (1977) and Melvin and Howard (1980), but nowhere more so than in an hour-long American Playhouse episode he made for public television in 1982: Who Am I This Time?

A haunting, beautiful question, since the drama enacted here by the two top-of-their-form stars is no less than their own individual hang-ups as actors. I do not see Helene Shaw, I see Susan Sarandon. I do not see Harry Nash, I see Christopher Walken. I see, in other words, not a fiction with characters but a living drama that spills into my world. I am moved—terribly. Who is the actor? Who am I, who are we, when we put on those age-old roles: lover, artist, dreamer, public figure? To what gestures and to which memories am I, in the end, reduced?

Demme drew his profound points from a master of US kook, Kurt Vonnegut, who wrote the short story “Who Am I This Time?” in 1961 and whose sense of the pointless, anguished fragility of life and love is kept in check by his rampant thirst for the absurd. Sarandon plays a traveling phone-company lady who intends to stay in the small town where the film is set for only eight weeks. But her low-key movie-star aura—don’t we all possess it secretly?—is attractive to the town locals, who rope her in to their amateur community-theater production of Tennessee Williams’s Streetcar Named Desire. She plays Stella opposite the Stanley of a painfully withdrawn hardware-store clerk: Walken. His is the sort of performance that would be “masterful” only by the standards of a public high school in Pasadena. And lo! Sarandon finds herself drawn to Walken, drawn into his boorish, leering, drawling Stanley, a parody of a bad Marlon Brando parody. Yet Walken is so parodic that he emerges as sincere, original, true. We get why she’s into him. He plays it as a bit without meaning it as a bit. That’s hot.

The townsfolk warn Sarandon: Don’t get too attached—he’s like that with every performance. Yes: as soon as a rehearsal or a show’s run is over, he goes back to being his normal, schlubby, gormless self.

What I love is that the story is told with limited settings (a store, a storefront, a fake New Orleans storefront, and a library), no flash, and is acted with the sense that this wildly mediocre, overacted production of Williams’s melodrama is a matter of life and death. Because it is. And you know what? I prefer it to the Elia Kazan film! Yes! So does Sarandon’s Helene, who prefers Walken’s Stanley over “the real thing,” Brando. That is love.

Should Sarandon go back to her regular job? Or does this weird performative relationship, so transitory and wonky, hold the key to her life? Ultimately she feels like she needs to stay on in the town in order to understand Walken’s complex, to try to see why he’s so painfully shy and withdrawn and can only be “himself” in roles that bear no relation to who he actually is. Every minute counts. The seconds tick away. Rehearsal—then opening night—then two more matinees—then closing night—then: strike the set and go back to your silly little humdrum lives. Hardly any time to stoke love. So Demme, Vonnegut, Sarandon, and Walken make you feel, in commercial-free miniature, that anxiety of waiting for a beloved to emerge. They make me see: to encounter a shy one’s face is just about the most mysterious, cataclysmic event that we can ever hope to experience.

Sofia Coppola’s On the Rocks (2020)

And so we come to a not-really-rom-com comedy of romance. As expected, Sofia Coppola nails the effervescence of rom-coms but plays none of the familiar notes, hits none of the “right” beats. But who wants to be right? Off is in.

The beau? None other than he to whom my heart belongs, Daddy (Bill Murray). Psychoanalysis nods: “This is where we came in.”

The premise: “Dad,” says Rashida Jones. “I think my husband is cheating.”

“The fink,” hisses Bill. “Let’s catch him with his Gucci trousers down.”

The reality: maybe there’s no cheating. Maybe it’s all in our heads. And maybe Dad knows it’s all in our heads. And maybe he’s letting this happen because he wants his little girl back. Maybe.

On the Rocks recalls, with subtlety, a host of masterpieces: lunatic Blake Edwards romances such as The Tamarind Seed (1974) and 10 (1979), Henry James’s novel The Sacred Fount (1905), the fantasy worlds of the haute riche as seen in films like George Cukor’s Holiday (1938) and Coppola’s own Lost in Translation (2003) and Somewhere (2010; my two favorites of hers). That’s frighteningly good company. That’s a dinner party. I can toast a glass of Chianti to all of them.

Clever people being clever? Nothing new under the sun. But now we see that the cleverness is a front for avoiding the void: facing your partner square in the eye. A 1930s absurdity and elegance are transposed, surrealistically, to the modern day, as in the films of Whit Stillman. This is not nostalgia; we know the world is not like this. This is fantasia. But we still have the same hang-ups in fantasia: will he be faithful? Will I?

On the Rocks is like The Sacred Fount in the fact that its two principals, father and daughter, talk themselves to death trying to figure out what’s happening in a marriage that’s going unlived by both parties. It’s a strange, charmingly archaic world where guys (yes, white; yes, old) can still get out of a criminal rap because the cop realizes that his arrest is buddies with his own papa. Coppola wanted to create, I think, something like a 1930s screwball but ended up—whoops!—creating an achingly sad romance peppered with freeing laughs. But On the Rocks is unthinkable without the history of the romantic comedy. It does what all great rom-coms do: it is precise with language, it hears the gaps. It’s not simply about rat-a-tat lines of grating precocity and cleverness: “I’m a man!” “Well, nobody’s perfect.”6 Zing. Tee-hee. Got ’em. So what. What comes in between? What comes before? What, after?

Life, and love, swirl in the pauses required to let the event of a belly laugh ease gracefully into a memory. It’s about how Murray, explaining why he’s gone deaf to women’s voices, swishes the word “pitch” in his mouth, rolling the “p” as if it were the Spanish “ñ.” It’s, in short, about waiting, and observing, and waiting some more. And then: the anarchic guffaw. Perhaps the sudden tear as well. They belong together.

Other inclusions in the Carlos Rom-Com Canon:

Me and My Gal (1932)

Love Affair (1939)

Christmas in July (1940)

The More The Merrier (1942)

The Long Long Trailer (1954)

Bells Are Ringing (1960)

Lolita (1962)

Loves of a Blonde (1966)

Arabesque (1966)

A Countess from Hong Kong (1967)

The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967)

Two for the Road (1967)

Stolen Kisses (1968)

Claudine (1974)

10 (1979)

They All Laughed (1981)

Moonstruck (1987)

Crossing Delancey (1988)

A Couch in New York (1996)

The Last Days of Disco (1998)

Down with Love (2003)

It’s Complicated (2009)

Silver Linings Playbook (2012)

Ferny and Luca (2021)

Diary of a Fleeting Affair (2022)

1Billy Mernit, Writing the Romantic Comedy. From “Cute Meet” to “Joyous Defeat”: How to Write Screenplays That Sell (New York: Harper Perennial, 2000), p. 13.

2Ibid., p. 252.

3Stanley Cavell, Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Film Studies, 1981).

4I prefer the modern Spanish word for “friendship,” amistad, since the root of the word is amor, or “love.” Though “friend” has its root in the Middle English word “frēond,” which also means “loved one” or “lover,” this meaning has been softened in modern English.

5My favorites: The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927), The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), Trouble in Paradise (1932), Broken Lullaby (1932), Design for Living (1933), Angel (1937), The Shop around the Corner (1940), To Be or Not To Be (1942), Heaven Can Wait (1943), and Cluny Brown (1946).

6The final line of Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959).