The Paris-based writer William Middleton is the author of Double Vision, a biography of the legendary art patrons and collectors Dominique and John de Menil, published in 2018 by Alfred A. Knopf. He has contributed to such publications as W, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Architectural Digest, House & Garden, Departures, Town & Country, the New York Times, and T. Middleton’s most recent book is Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld published by HarperCollins in February 2023.

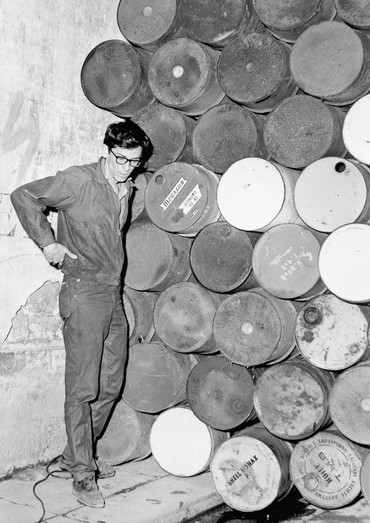

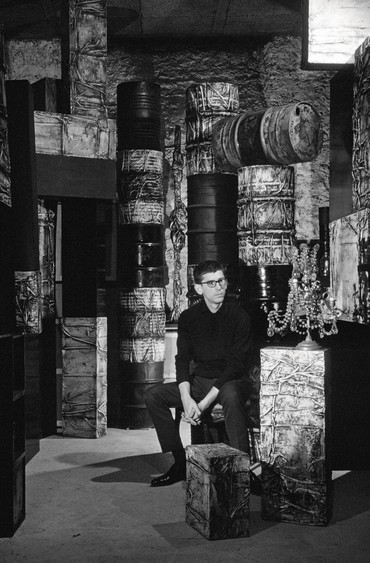

Sixty years ago, on the night of June 27, 1962, the rue Visconti, a charming street on the Left Bank that is one of the narrowest passages in Paris, was the setting for a guerrilla art installation. This striking piece, Wall of Oil Barrels—The Iron Curtain, was by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, and was only the second collaboration in their young career. It consisted of eighty-nine oil barrels stacked on top of one another, over fourteen feet in height, that stretched from wall to wall, completely blocking the street. Although The Iron Curtain stood for eight hours, it set off a series of shockwaves that have reverberated throughout the decades.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude had requested permission from Paris officials to construct the work but had not heard back. They intended to build the piece on the night of an exhibition opening that Christo was having at the Galerie J, his first solo show in the city. “Since our idea was technically never rejected, but simply ignored, Jeanne-Claude and I decided to do it anyway,” he later explained. “It was built very fast and was only up for one night, from 6pm to 1am It stopped traffic—people got very upset—then the police arrived.”1

In the summer of 1962, the political environment in France was heated, with the Algerian War of Independence just coming to its bloody conclusion. So installing The Iron Curtain without authorization was a bold act, particularly for Christo, who had defected from Communist Bulgaria in 1956. “I did many illegal things in those days,” Christo later stated. “I escaped from the Communist bloc to the West—that was illegal. I tried to go to Paris illegally. Sometimes, artists do illegal things.”2

The impulse for The Iron Curtain had come the year before, when Christo and Jeanne-Claude were in Cologne for his exhibition at the Galerie Haro Lauhus and the first piece they had created together, Stacked Oil Barrels and Dockside Packages, Cologne Harbor (1961), a grouping of oil barrels, some wrapped in large tarps and secured with ropes, that were stacked on the city docks. During their stay in Germany, a major historical development took place hours northeast of Cologne, an action that was terrifying for Christo. “The Cologne exhibition opened in June 1961 and the Berlin Wall was built on the night of August 12 to 13, 1961,” Christo explained, remembering the dates even decades later. “I was still a political refugee without a passport, without a nationality, and, of course, with this terrible fear that the communists would catch me. When the situation with the Soviets and the West had become increasingly tense, I reacted. I made the very modest proposal of building a wall of barrels on the rue Visconti—it was the aesthetic response of an artist.”3

Christo’s nephew Vladimir Yavachev, who worked closely with the artists after 1990, when he moved to New York from Bulgaria at the age of seventeen, witnessed how geopolitics had shaped his uncle. “Throughout his life, it defined him,” Yavachev points out. “Not just the Berlin Wall but the whole Cold War and the division between East and West. Especially because he really escaped—he was a political refugee. He always said, ‘I do the work I do because of where I come from and the experience that I had coming from the East.’”4

The Iron Curtain attracted quite the audience, including such artists as Arman, René Bertholo, Lourdes Castro, Niki de Saint Phalle, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely, and Jan Voss; the influential French critic Pierre Restany; and such dealers as Sidney Janis and Leo Castelli.5 “It was a fantastic piece, extraordinarily beautiful,” Castelli said of The Iron Curtain. “It was really something to block an entire street like that. It was a statement that was Duchampian, very Dada, which I understood quite well because I saw it in other artists I was representing: [Robert] Rauschenberg, [Roy] Lichtenstein, [Claes] Oldenburg, [Jasper] Johns.”6 Convinced by The Iron Curtain, Castelli encouraged Christo and Jeanne-Claude to move to New York. He assured them that the center of the art world was shifting from Paris and he gave Christo his first American group show, Four, in 1964, and his first solo exhibition, Four Store Fronts Corner (1964–1965), in 1966.

“The Iron Curtain is one of the most interesting early works,” explains Lorenza Giovanelli, an art historian who works with the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation. “It really exposed Christo to the international art scene. It lasted just a few hours but it had such a strong and deep impact on Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s career—it was actually their ticket to New York.”7

Christo Javacheff was born in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1935. Interested in art from his early childhood, and drawing from the time he was five years old, he took private lessons with painters and sculptors who were friends of his parents. He then pursued his education in traditional schools modeled on the nineteenth-century German academies.8 “He was very classically trained in the Sofia art academy, which was a very old-fashioned art school,” explains Yavachev. “He had two semesters of dissecting human bodies to see how the muscles work—it was old school.” In the fall of 1956, Christo was able to visit family in Prague, and then escaped to Vienna in a freight car. After a stay in Geneva, he arrived in Paris in 1958. To make money he painted portraits of society figures.

In October 1958, through portraits he did of the entire family, Christo met Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, whose stepfather, Jacques de Guille-bon, was a French general and director of the École Polytechnique, one of the most prestigious universities in France.9 They quickly embarked on a personal and creative partnership that would last for the rest of their lives. (Both born in 1935—actually on the same date—Jeanne-Claude died in 2009, Christo in 2020.)

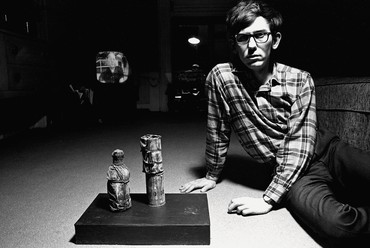

Christo’s years in Paris, from 1958 until 1964, are considered the period of his early works. Wrapped objects and mysterious packages were key elements of his first personal pieces. A few striking examples: Package (1959), a tall, slender form covered with fabric, twine, and rope on a simple base, a black-painted wooden square; Wrapped Oil Barrels (1958), three steel oil barrels wrapped in painted fabric and wire; Wrapped Cans (1959), five metal cans covered in lacquered fabric; Package on Baby Carriage (1962), a baby stroller wrapped in pink plastic and twine; and Wrapped Car (Volkswagen) (1963), a VW Beetle wrapped with rubberized tarp and rope. At the studio of the artist Yves Klein on the rue Campagne Première, he even wrapped one of Klein’s models in plastic and twine.

“It was really in Paris that he became Christo,” points out Yavachev. “Before, with the portraits, very figurative, he signed using his last name, Javacheff. Once he started doing packages, and wrappings, and barrels, those are the first works that he signed as Christo.”

The use of oil drums as a material came for very practical reasons: they cost little or nothing and Christo had a studio in the Paris suburb of Gentilly that was next to a stockpile of used oil barrels. “Often, he would combine barrels with other found objects to create totemlike compositions, tall columns or peculiar, shorter sculptures,” explains Giovanelli. “Although they are no longer in existence, unfortunately, they show how Christo was curious about architecture itself, the architecture of the object, and the interaction of the object with space.”10

Instead of continuing to wrap barrels, Christo began to focus on them more as raw material, a kind of readymade. “The sculptures became more purist,” Giovanelli says:

He would not even clean them or repaint the barrels. He wanted to use them exactly as they were. By doing that, he was really incorporating the real world in his work, which is what they went on to do in the large projects throughout their career. For The Iron Curtain, he didn’t want to use pristine or new barrels, or paint the barrels, he used what he could find. First, because they were free—Christo was very poor, so he would use everything that he could to create his work. But mostly because he found that aspect fascinating, for capturing the real world in his work.11

Although it may seem a dramatic leap from the early barrels and wrapped pieces to such grandiose projects as The London Mastaba (2016–18) or L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped (1961–2021), there was actually a continuity. In fact, the first iteration of a project to wrap the Arc de Triomphe came in 1961, when Christo had a studio not far from the monument in the seventeenth arrondissement. “The large projects that Christo realized with Jeanne-Claude find their roots in the early works that he began to create when he moved to Paris,” says Giovanelli. “In the early works one could see all the aspects that will characterize the later larger outdoor installations: the nomadic quality of the fabric, the concealment, the installation of modular elements in an environment, the attention to the surface and a tension between the interaction of the viewer with the object, the object with the whole environment, and therefore the viewer with the environment itself. In this sense, the projects are the natural consequence of the early works.”12

Once Christo and Jeanne-Claude began working together on their large-scale projects, they decided to sign their work jointly (all of the sculptures and preparatory works—drawings and models—were done solely by Christo). The order of their names was not accidental. In 1998, Jeanne-Claude wrote a text correcting frequent mistakes about their lives and their work: “Because Christo was already an artist when they met in 1958 in Paris, and Jeanne-Claude was not an artist then, they have decided that their name will be ‘Christo and Jeanne-Claude,’ not ‘Jeanne-Claude and Christo.’” Charming but firm, her text correcting the official record, entitled “Most Common Errors,” is published on the foundation’s website.13

A crucial aspect of the careers of Christo and Jeanne-Claude is that they intentionally surrounded themselves with a team of like-minded spirits. Their term for this group: “a working family.” One key member has been Matthias Koddenberg, who first made contact with the artists in 1995, when, as an eleven-year-old in Germany, he saw what they had done with the German parliament in Berlin, Wrapped Reichstag (1971–95). “I saw that on television, and I was just so fascinated,” Koddenberg explains. “I had no ideas about art or what that meant but I was overwhelmed, and went and got a book about them. And in the book, I found part of their address in New York. I wrote them a letter, asked for an autograph, and some weeks later I got a huge package from Jeanne-Claude, filled with books and postcards and everything.”14

That was the beginning of a long correspondence and working relationship. Koddenberg would travel to see their exhibitions and eventually, after studying art history, spent time with them in New York while doing an internship at the Morgan Library. He threw himself into researching their work, conducting extensive interviews with Christo. “They were always very eager to surround themselves with young people,” Koddenberg observes. “They were very much aware of having future generations talk about the art because all the projects were only temporary. There is only documentation, so it was important to have young people on the team who can speak about their art and their personalities and their intentions.”15

Many elements of Christo’s work of course do endure, including all of the early sculptures and the preparatory works for the large-scale projects. “All the drawings and collages are preparatory works for the installations,” Koddenberg explains. “They have a lot of technical details and Christo often incorporated maps and construction drawings into his collages. They are works of art on their own and they were all done by Christo. He never had an assistant in his studio—every line was done by Christo himself. Artistically they are very beautiful, and they are very, very valuable pieces of art themselves.”16

Giovanelli, born and raised in Italy, was also swept up into the world of Christo and Jeanne-Claude at a young age. Just after earning her master’s in art history, she was hired to be the office manager for The Floating Piers (2014–16), on Lake Iseo, near Brescia. “After it was finished, I spent a long time taking care of the dismantling of the project and the recycling of all the materials,” Giovanelli recalls. “So I was the last man standing. I closed the gates of the construction site on the lake in February 2017, and right after, Christo himself called me up and asked if I wanted to move to New York and join the core team.”17 She was given an apartment in the building on Howard Street, SoHo, where Christo and Jeanne-Claude had lived and worked since just after they’d moved to New York.

All involved in the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation agree on the significance of The Iron Curtain to understanding the artists’ work. “It was the first big one that they did outside in the streets and it was the beginning of all the bigger projects that followed,” says Koddenberg. “From the beginning, it was their intention to confront people with their art who are not normally going to museums or galleries, normal people using the city and the streets. They wanted to confront them with art and to see how they react, to find out whether they like it or not, to get into discussions with them about the piece and the art and how they use the space and the city and the landscape. So this was the beginning.”18

Earlier this year, on the sixtieth anniversary of The Iron Curtain, the Foundation conceived of an original way to commemorate this ephemeral piece: they installed a permanent record on the rue Visconti, just off the rue de Seine between numbers 1 and 2, on the exact site of the original sculpture. “We put out a sign to make people aware that the project happened there in 1962,” Koddenberg says. “And now, it’s very elegant, you will hardly see it, but if you look down on the street, you will see there is a marking where the wall was originally. And we did an augmented reality of the original wall. So you take your smartphone and you scan a QR code, which is now on the side of the street. The wall appears on your phone and you can direct it to the place where it was and then you see it on your phone as if it’s still there. So you can better imagine the size and dimensions of the piece.”19

Giovanelli feels that The Iron Curtain is increasingly relevant to understanding Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s larger intentions. “I think it’s important because it’s the first urban project,” she says. “Dockside Packages and Stacked Oil Barrels installed at the Cologne harbor was officially Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s first project, but in Paris they really engaged with the city environment. It created the very first ‘gentle disturbance,’ which is how Christo and Jeanne-Claude described their works. Their temporary disturbance was gentle as they created something that would have an effect on the people who lived or visited that place, but after a few days or weeks they would take it away and everything would quietly disappear, as though nothing had ever happened. So this was the very first time that they created a gentle disturbance in a public context.”20

Although The Iron Curtain was much larger than anything that Christo and Jeanne-Claude had created up to that point, it was modest compared with what would come within just a few years. In 1967, for example, they envisioned wrapping the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome; in 1968, they proposed blocking West 53rd Street, Manhattan, in front of the Museum of Modern Art, with a wall made of hundreds of oil barrels; while in 1969, working with the collectors Dominique and John de Menil, they envisioned a mastaba built of 1,249,000 oil drums in the Houston-Galveston area.21 And they realized the first of their massive projects, Wrapped Coast, One Million Square Feet (1968–69), when they used erosion-control fabric to wrap 1 1/2 miles of rugged cliffs along the Australian coast, south of Sydney. As Giovanelli summarizes, “In 1964, they moved to New York, and, in terms of scale, the whole vision changes.”22

1Christo, quoted in Matthias Koddenberg, Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Early Years. An Interview by Matthias Koddenberg (Dortmund: Verlag Kettler, 2020), p. 87.

2Ibid., p. 87.

3Christo, in Olivier Kaeppelin, Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Barrels/Barils (Paris: L’Arche, 2016), p. 60.

4Vladimir Yavachev, interview with the author, July 15, 2022.

5Lorenza Giovanelli, email to the author, July 19, 2022.

6Leo Castelli, quoted in Laure Martin-Poulet, “De la rue Visconti au Pont-Neuf. Les Projets parisiens de Christo et Jeanne-Claude,” in Sophie Duplaix, Christo et Jeanne-Claude. Paris!, exh. cat. (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2020), p. 153.

7Giovanelli, interview with the author, July 13, 2022.

8See Koddenberg, The Early Years, p. 7.

9Ibid., p. 21.

10Giovanelli, interview with the author.

11Ibid.

12Ibid.

13Jeanne-Claude, “Most Common Errors,” 1998. Available on line at https://christojeanneclaude.net/most-common-errors/ (accessed July 23, 2022).

14Koddenberg, interview with the author, July 14, 2022.

15Ibid.

16Ibid.

17Giovanelli, interview with the author.

18Koddenberg, interview with the author.

19Ibid.

20Giovanelli, interview with the author.

21David Aylsworth, the Menil Collection, email to the author, June 19, 2018.

22Giovanelli, interview with the author.

Christo: Early Works, 1958–1963, Gagosian, rue de Ponthieu, Paris, June 10–October 8, 2022

Artwork © Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation