Salomé Gómez-Upegui is a Colombian-American writer and creative consultant based in Miami. She writes about art, gender, social justice, and climate change for a wide range of publications, and is the author of the book Feminista Por Accidente (2021).

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Roe v. Wade, a landmark decision that had protected the federal right to abortion since 1973. Overnight, although a wide majority of Americans believe abortion should be legal, millions of people who can get pregnant were stripped of their reproductive rights.1 Thirteen states have fully banned most abortions, five states have imposed strict time limits between conception and abortion, and many other states are pushing for legislation to block women’s right to choose.2

“The striking down of Roe should come as a surprise to no one. And if it does, they haven’t been paying attention,” the American artist Barbara Kruger said after the court’s regressive decision.3 Indeed, feminist activists have been warning about the probability of this devastating blow to reproductive rights in the United States for years now, especially since 2016 and the election to the White House of Donald Trump, whose appointment of conservative justices Amy Coney Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh, and Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court changed the ideological makeup of the highest judicial body in the land.

Like Kruger, many artists in the United States, including Laurie Simmons and Judy Chicago, have expressed their disgust with the Supreme Court’s decision.4 Even before then, perhaps intuiting the impending attack on women’s basic human rights, many stood up to advance the cause of choice, revealing the importance of art in raising not just awareness but often critical funds, and in significantly affecting pivotal elections as well.

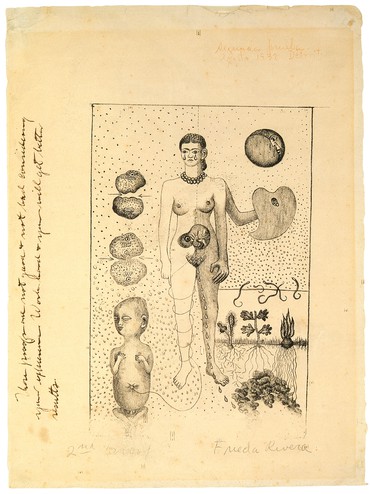

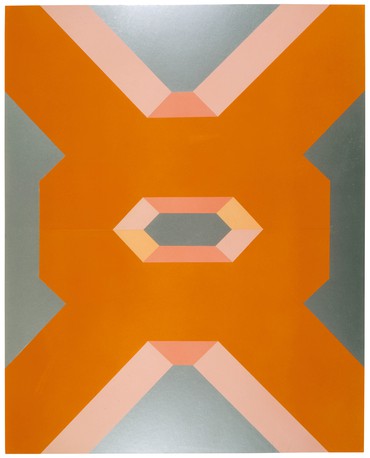

Still, at least in the Western art canon, this clear stance in favor of reproductive justice has historically been uncommon. While works idealizing motherhood and virginity are omnipresent, those depicting or exploring abortion, such as Frida Kahlo’s lithograph El Aborto (also called Frida and the Miscarriage or Frida and the Abortion, 1932), are rare to the point of nonexistent in the first half of the twentieth century, not to mention before then. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, though, with the emergence of the feminist art movement in the United States, the overwhelming silence on women’s rights in the country’s art world began to fade. In its place, powerful bodies of work by artists such as Marilyn Minter and Miriam Schapiro emerged to advance women’s liberation. Between 1967 and 1971, for example, Schapiro created a series of computer-generated works, including Big Ox (1967) and Keyhole (1971), riddled with symbolic imagery alluding to female reproductive organs. “For once in the history of art, it was not the penis that was praised, not the ubiquitous phallic symbol, it was a woman’s hymn to her body. At last, one could acclaim that component of the female anatomy,” Schapiro famously said about these pieces.5

Hannah Wilke was one of the first artists to turn to vaginal iconography during this period, with acclaimed works such as S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974–82). She denounced women’s status as second-class citizens through a performance and resulting photograph series in which she posed with pieces of chewed gum, shaped to resemble miniature vulvas, on her naked body. And in the 1980s, Chicago created her renowned Birth Project series (1980–85), an expansive set of textile works that honored and explored women’s ability to bring life into the world. In 1983, Chicago donated Birth Trinity Quilt Batik (1983), a piece from this series, to Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains, Denver, Colorado.

Regardless, while critical questions around womanhood, sexuality, and bodily autonomy began to be raised in the late 1960s, works unequivocally addressing the subject of abortion remained, with notable exceptions, few and far between. One such exception is Juanita McNeely’s Is it Real? Yes it is! (1969), an enormous nine-panel painting that recounts McNeely’s experience of illegal abortion in the 1960s. The piece was acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in 2022. In its ninety years of existence until then, the museum held no paintings explicitly dealing with abortion in its permanent collection, a fact that speaks volumes about the magnitude of this taboo in the American art world.6

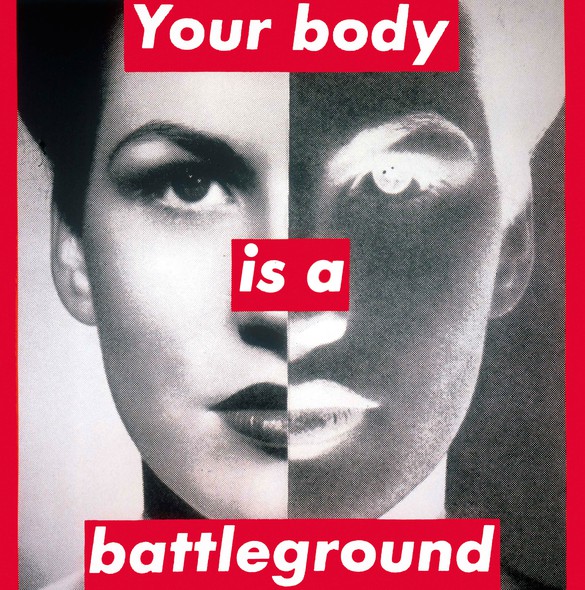

Kruger was one of the few artists who defied the status quo and unabashedly created pieces tackling issues of reproductive justice when almost no one else dared to do so. During the 1980s, when Roe v. Wade was already the law of the land, a resurgence of anti-abortion laws resulted in numerous pro-choice protests and demonstrations around the country. Against this backdrop, Kruger created the now iconic works Untitled (How come only the unborn have the right to life?) (1986) and Untitled (Your body is a battleground) (1989).7 The latter, which she designed for the 1989 Women’s March in Washington, DC, has appeared at feminist protests demanding the right to abortion and birth control ever since; in 2020 it was widely used by Polish feminists protesting a government ban on abortion in that country. Speaking about the troubling continued relevance of works such as this, Kruger has said, “It would be kind of good if my work became archaic.”8

An all-text poster by the feminist art group Guerrilla Girls, Guerrilla Girls Demand a Return to Traditional Values on Abortion (1992), was another rare artwork that openly addressed the unthinkable: it reads, “Before the mid-19th century, abortion in the first few months of pregnancy was legal. Even the Catholic Church did not forbid it until 1869.” More than thirty years after it was produced, the piece is still commonly spotted at protests today.

Beyond the United States, Portuguese-British artist Paula Rego was in a category of her own for her now acclaimed series of pastels and etchings portraying illegal abortions. She began these pieces in 1998 after Portugal staged a referendum on legalizing abortion, which failed to pass. As Rego said of one of the etchings, it “highlights the fear and pain and danger of an illegal abortion, which is what desperate women have always resorted to.”9 The artist considered these works some of her best “because they are true, and they were effective in helping to change the law in Portugal.”10 Abortion was legalized in Portugal after a second referendum in 2007.

The timidity of American artists and institutions in addressing abortion has increasingly dissipated in recent years. One remarkable example was the expansive exhibition Abortion Is Normal, which opened at Project for Empty Space, Newark, New Jersey, in 2019 and became the first of a multi-part series of exhibitions. The project continued a year later in New York with an “emergency exhibition” curated by Jasmine Wahi and Rebecca Pauline Jampol and coorganized by Minter, Simmons, Gina Nanni, and Sandy Tait. This trailblazing show was backed by the political action committee Downtown for Democracy and sold works by over sixty artists to raise funds to advance women’s reproductive rights. Standout works in the show included queer activist Viva Ruiz’s Thank God for Abortion (2015–), extracted from a multiplatform art project, and Minter’s CUNTROL (2020), a triptych featuring three provocative photographs of a woman behind a steamy glass.

Minter, who has been outspoken about getting an abortion at Planned Parenthood in her early adulthood, has been at the forefront of pro-choice activism in the United States for decades. In 2015 she helped organize Choice Works, an initiative that auctioned works of art to fund Planned Parenthood programs at the local and national level. In 2016 she was honored with Planned Parenthood’s prestigious Woman of Valor award. And in 2020, looking to sway voters in that year’s presidential election, she again collaborated with Downtown for Democracy to produce My Vote (2020), a short video featuring actress Amber Heard that commences with a powerful quote by by Louis Brandeis, often referenced by Ruth Bader Ginsburg: “the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people.”

The year 2022 was momentous for art addressing abortion in the United States. In May, after the news website Politico leaked a draft of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, Minter published an op-ed in Artnews, anticipating Kruger’s comment after the decision was formalized: “This is a hard moment to process, although if you’ve been paying attention, you knew it was coming. . . . The violence and shattering of any sense of safety as a woman is not an unfortunate by-product. It is the point.”11

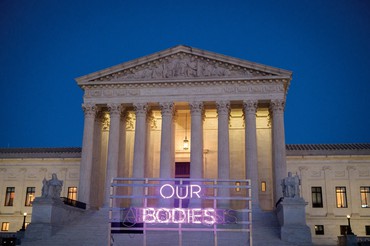

Earlier that year, Dallas-based artist Alicia Eggert partnered with Sarah Sandman, creative director of advocacy at Planned Parenthood Federation of America, to create OURs, a large pink-neon-light installation that cycles through the phrases “our bodies,” “our futures,” and “our abortions” to quite literally illuminate the matter of abortion access. Symbolically, the piece was initially displayed outside the Supreme Court Building in Washington, DC, and then traveled across the United States. Eggert has said, “The reason that I work in signage is because of how quickly and effectively it can grab peoples’ attention. You can’t not see it. You can’t not read it. . . . Our bodies, our future, our abortions—you can’t have one without the other.”12

Another public-art project that made waves last year was Vote for Abortion Rights, a billboard campaign led by Swedish-American artist Michele Pred with the Brooklyn-based nonprofit SaveArtSpace. The project set public artworks across twelve states. The billboards, selected from more than 400 open-entry submissions, bluntly advocated for abortion with phrases inspired by the language usually used in political ads. Holly Ballard Martz’s, for example, read “Abortion is healthcare,” and Lena Wolff and Hope Meng’s read “Vote! for reproductive freedom.”

Also in 2022, Brooklyn-based A.I.R. Gallery collaborated with the National Women’s Liberation group to show Trigger Planting (2022) at Frieze New York. This was a fascinating installation by the art collective “how to perform an abortion” (Kadambari Baxi, Maureen Connor, and Landon Newton), which has been studying herbal abortifacients since 2017. Using plants commonly used for contraception and abortion, the group created a forty-five-foot-tall herb garden that mapped the American states with the most stringent anti-abortion laws already on the books when Roe v. Wade was overturned. Without Roe, these laws, also known as “trigger laws,” went into effect, producing instant abortion bans.13

The examples don’t stop there. When the Supreme Court officially released its decision to strip millions of people of their reproductive rights last June, artists continued to speak up and stand up. The conceptual artist Jenny Holzer, for example, sold an NFT to benefit organizations fighting for reproductive justice. The work showed a screenshot from the right-wing late-night Fox News talk show Tucker Carlson Tonight, with a chyron reading “making an informed choice regarding your own body shouldn’t be controversial.” The chyron had appeared in the context of an attack on vaccine mandates; it does of course apply just as logically to the abortion debate, although Carlson would be unlikely to use it there. Louise Bonnet’s striking painting Red Study (2022) shows a conical stream of blood emanating from between a woman’s legs. “It could be her period, a miscarriage, or an abortion, or indeed another medical situation—it’s ambiguous. [But] she’s not victimized,” Bonnet has explained.14 The artist donated the proceeds from the sale of the painting to Planned Parenthood.

Last fall, Miami-based artist and Planned Parenthood board member Antonia Wright set up an exhibition at Spinello Projects, Miami, entitled I Came to See the Damage That Was Done and the Treasures That Prevail—a quotation from a poem by Adrienne Rich. The show presented a series of works that Wright had created in response to the crisis in reproductive rights. The standout Women in Labor (2022), a sound piece, uses an algorithm to create sounds that map the increased distances that women will now have to travel to access reproductive healthcare. Echoing the feminist slogan “The personal is political,” the sounds Wright used in the piece were sourced from her own home birth experience in 2015, as well as from others that she collected by partnering with midwives.

Also expanding on her personal background, Ethiopian-American artist Tsedaye Makonnen uses her experiences as both a mother and a doula to make works that shed light on the acutely important issue of reproductive-healthcare inequalities faced by Black women in the United States today. In the ongoing Crowning Series (2017– ), which includes performances, sculptures, and photography, the artist delves into themes of abortion access and “the womb as wound.” The artist has said, “My use of pelvic bones [in The Crowning Series] . . . is about reproductive health, which includes abortion. Why is it that Black women have the most womb issues of all people? What the fuck is that about?”15

Less than a year after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the future of reproductive rights in the United States is riddled with dread and uncertainty. In March 2023, six works about abortion were removed from an exhibition at Lewis-Clark State College in Lewiston, Idaho. The college cited a state anti-abortion law enacted in 2021 that forbids using state funds to “promote abortion” or “counsel in favor of abortion.”16 Among the works censored was With all my pleas with doctors they won’t do anything (2023), by Chicago-based artist Michelle Hartney, a text-based piece that quotes a letter received by feminist activist Margaret Sanger in the 1920s from a woman desperately seeking to prevent an unwanted pregnancy. A century later, her cry for help still seems terrifyingly current. And while the artists mentioned in this essay—which is far from an exhaustive review of the subject—have stood up and made important statements, the need for artists to address abortion and reproductive justice unashamedly and from an intersectional perspective is more urgent than ever.

1See Christine Filer, “With Supreme Court Poised to Reverse Roe, Most Americans Support Abortion Rights: POLL,” ABC News, May 3, 2022. Available online at https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/supreme-court-poised-reverse-roe-americans-support-abortion/story?id=84468131 (accessed March 14, 2023).

2See “Tracking the States Where Abortion Is Now Banned,” New York Times, February 10, 2023. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html (accessed March 14, 2023).

3Barbara Kruger, quoted in Angelica Villa, “Legendary Artists Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Nan Goldin Respond to Roe Draft Opinion: ‘A Surprise to No One,’” Artnews, May 4, 2022. Available online at https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/barbara-kruger-jenny-holzer-nan-goldin-artists-respond-to-roe-supreme-court-draft-opinion-1234627508/ (accessed March 14, 2023).

4See ibid.

5Miriam Schapiro, quoted in Maddy Henkin, “Miriam Schapiro’s Feminist Artwork Finds New Life in 2022,” L’Officiel, November 27, 2022. Available online at https://www.lofficielusa.com/art/miriam-schapiro-feminist-artist-womens-reproductive-rights (accessed March 14, 2023).

6See Deborah Solomon, “After Decades of Silence, Art about Abortion (Cautiously) Enters the Establishment,” New York Times, September 10, 2022. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/10/arts/design/art-abortion-whitney-javits-museums-galleries.html (accessed March 15, 2023).

7See Alexander Schneider, “Your Body Is a Battleground: Artworks by Barbara Kruger and Edward Kienholz on Abortion,” Unframed (LACMA), May 18, 2022. Available online at https://unframed.lacma.org/2022/05/10/your-body-battleground-artworks-barbara-kruger-and-edward-kienholz-abortion (accessed March 15, 2023).

8Kruger, quoted in Carolina A. Miranda, “As Roe vs. Wade teeters, Barbara Kruger’s ‘Your body is a battleground’ takes on urgency,” Los Angeles Times, May 3, 2022. Available online at https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2022-05-03/roe-vs-wade-supreme-court-decision-and-barbara-kruger-your-body-is-a-battleground (accessed March 15, 2023).

9Paula Rego, quoted in Lanre Bakare, “Paula Rego calls US anti-abortion drive ‘grotesque,’” Guardian, May 31, 2019. Available online at https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/may/31/paula-rego-calls-us-anti-abortion-drive-grotesque (accessed March 15, 2023).

10Rego, quoted in Margaret Carrigan, “Paula Rego’s influence will live on—here’s why her market will too,” Art Newspaper, July 28, 2022. Available online at https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/07/28/paula-regos-influence-will-live-onand-her-market-will-too (accessed March 15, 2023).

11Marilyn Minter, “Artist and Activist Marilyn Minter on Roe Leak: This Is ‘What Minority Rule Looks Like,’” Artnews, May 5, 2022. Available online at https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/artist-and-activist-marilyn-minter-on-roe-wade-supreme-court-leak-1234627748/ (accessed March 15, 2023).

12Alicia Eggert, quoted in Villa, “Legendary Artists Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Nan Goldin.”

13See Sarah Cascone, “At Frieze, a 45-Foot Herb Garden Is an Unlikely, and Highly Effective, Visualization of the Threat to Women’s Reproductive Rights,” Artnet News, May 19, 2022. Available online at https://news.artnet.com/market/frieze-how-to-perform-abortion-2117877 (accessed March 15, 2023).

4Louise Bonnet, in Freja Harrell, “Louise Bonnet: On ‘Red Study’ and Supporting Reproductive Rights,” Gagosian Quarterly, February 1, 2023. Available online at https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2023/02/01/interview-louise-bonnet-on-red-study-and-supporting-reproductive-rights/ (accessed March 15, 2023).

15Tsedaye Makonnen, in Ayanna Dozier, “Tsedaye Makonnen’s Art Addresses Reproductive Healthcare Inequalities Affecting Black Women,” Artsy, May 6, 2022. Available online at https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-tsedaye-makonnens-art-addresses-reproductive-healthcare-inequalities-black-women (accessed March 15, 2023).

16See Brian Boucher, “An Idaho College Removes Artwork About Abortion, Citing a State Law,” New York Times, March 13, 2023. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/13/arts/design/idaho-abortion-lewis-clark-college.html (accessed March 21, 2023).