James Lawrence is a critic and historian of postwar and contemporary art. He is a frequent contributor to the Burlington Magazine and his writings appear in many gallery and museum publications around the world. Photo: William Davie

The Ateneo Veneto, a scholarly society that has enlivened Venetian life for more than two hundred years, has its origins in the quality of mercy. In the mid-fifteenth century, two confraternities based near the church of San Fantin offered medical care. They also became known for accompanying condemned prisoners in their final moments. Over time, the confraternities became a scuola that gained permanent accommodation, lost it to fire in 1562, and gained new accommodation, a handsome Baroque structure near La Fenice. The scuola has passed into history but its building has housed the Ateneo Veneto since the days of Napoleon. The largest room on the ground floor, the Aula Magna, originally served as a chapel. Its splendors include a cycle of paintings by Palma Giovane, depicting Purgatory, that embellishes the coffered ceiling. During the 2019 Venice Biennale, the Aula Magna contains a modest chamber very different in mood from the torsion and chiaroscuro of Palma’s cycle. This chamber forms one part of Edmund de Waal’s exhibition psalm.

psalm takes inspiration from the history of Venetian Jewish culture, and most of all from the aesthetic legacy of that culture’s spiritual and intellectual traditions. The exhibition and its constituent parts are rooted in the openness of language: its unfolding debates, its shifting translations, and its availability for reconfiguration over time. Part of the exhibition takes place in one of the Venetian Ghetto’s five synagogues, the Scuola Canton, where de Waal has designed an encompassing installation that includes pieces of gilded porcelain in certain rooms. A series of eleven vitrines responds to the building’s gilded windows in a physical and visual allusion to the vocal interplay of cantor and congregation in responsorial psalmody. The act of singing is a prime example of how performance quickens or enhances the latent meaning in objects and information.

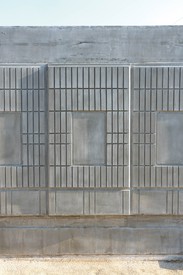

The other part of psalm is a chamber that de Waal has constructed in the Ateneo Veneto’s Aula Magna. He has designed the chamber as a self-contained library with walls of porcelain with inscriptions in gold leaf. Inside the chamber are two thousand books of poetry, mostly in translation, by exiled writers. The chamber, which has the scale of a private library or reading room, invites devotion to the written word rather than bibliographic awe.

Two elements of de Waal’s library give this celebration of literary porosity and expansiveness distinctive contours that testify—sometimes painfully—to the material power of organized words. Inside the porcelain chamber, de Waal has embedded a quartet of vitrines that take their formal cues from Daniel Bomberg’s seminal editio princeps of the Babylonian Talmud, published 1519–23. The exterior of the chamber, however, carries inscriptions of the names of lost libraries, most of them destroyed or stolen because of Jewish contents or Jewish ownership. One of those libraries belonged to Walter Benjamin, who committed suicide in 1940 after failing to escape from German-occupied Europe. Another was the notable private collection that belonged to de Waal’s Viennese great-grandfather, Viktor von Ephrussi, until the Nazis expropriated Palais Ephrussi and its contents in 1938.

Bomberg’s design, which developed out of the elegant arrangement of text, commentary, and glosses that the Jewish printer Joshua Solomon Soncino had established forty years before, remains a model of visual and exegetical clarity. The layout also holds the promise of fecundity: an implicit recognition that through commentary and criticism, meaning expands or unfolds from source to reconfiguration as a new source for further development. That reconfiguration often involves translation into new languages with their own traditions and habits of commentary, such as the art-historical discussion that the monochromatic crispness of de Waal’s vitrines might generate. No matter how far discussion might stray into uncharted areas, however, the source—the specific material that prompts what follows—remains present. That holds true for literary culture and for art history, even when presence is merely a recollection of something that is no longer intact.

To gauge the significance of libraries as components of a culture, it is sufficient to consider the effects of their elimination. Whereas the loss of a great work of art or architecture is tragic, the loss of a library—specifically, of the accumulated textual material that constitutes one definition of the word—can rend the fabric of understanding and memory that gives any culture its identity. Genocidal regimes routinely seek to eradicate not only populations but also their books.

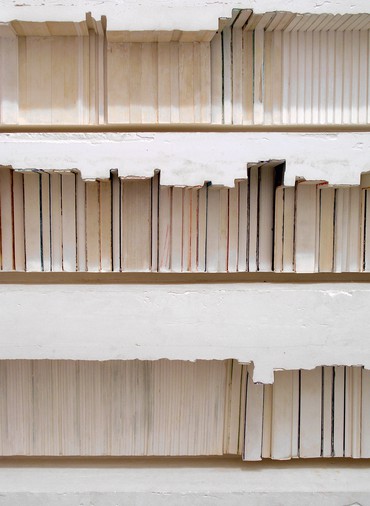

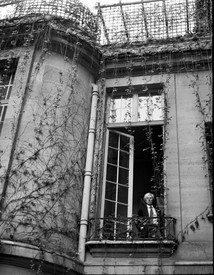

Less than half a mile from Palais Ephrussi, Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust memorial (2000) stands in mute tribute to the 65,000 Austrian Jews murdered by the Third Reich and its accomplices. Mute, because the emotional tenor of Whiteread’s “nameless library” is introspective and unforthcoming: it declines to explain what is terrible beyond words; it denies the comforts of the specifics that might give life and death meaning. Whiteread’s casting technique, which excels at breaking the spell of spatial overfamiliarity, elevates the memorial’s sepulchral gravitas to a higher plane of allusion where the uniform bookshelves suggest a violation of privacy: the simultaneous loss and forcible exposure of the interior life. Whereas Whiteread’s earlier works cast from bookcases, such as Untitled (Novels) (1999), recorded the physical characteristics and irregularities of real books in their natural habitat—down to the pigments of their bindings—her “nameless library” brings the poignancy of tactile familiarity into the stark, chilling light of existential indifference.

Whiteread’s memorial draws out the anthropomorphic implications of books as individual parts of a communal whole. The very notion of a library as a collection of objects is only meaningful through differentiation; a collection of identical books is not a library but a stockpile. The advent of printing was also the advent of firm authorial (or at least editorial) identity, the enduring association of a book with the person who produced it. A library is a social model, not merely an intellectual, literary, or material one.

Christian Boltanski’s Les abonnés du téléphone (2000), a work that he continues to recapitulate and adjust for local conditions, presents three thousand telephone directories in a library setting. As in any library, there is an implicit indeterminacy to this selective demographic record, which captures fixed instances in an ever-evolving body of knowledge. Boltanski’s project hints at the totalizing and static conditions of exhaustive information, but also embodies the limitations—the acknowledged constraints imposed by space and time—that make information meaningful as material for knowledge.

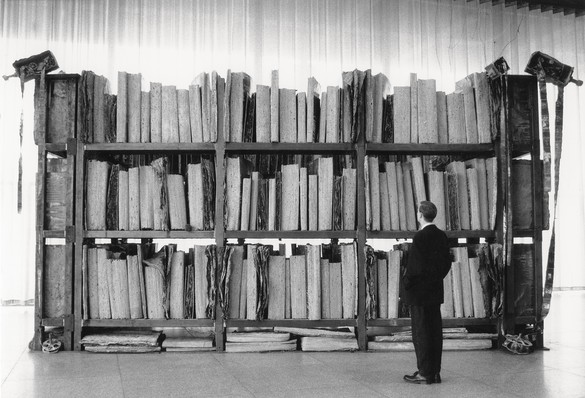

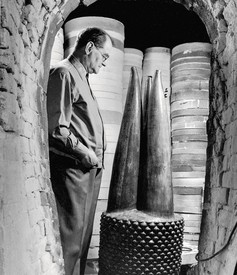

Books, and the libraries that contain them, encourage meandering within physical limits that suggest paths and focal points without requiring strict obedience. We browse; we skip and scan. Something catches our eye and leads us to another path. The spirit of prolific curiosity that inhabits Anselm Kiefer’s work, for example, affects us not simply because it animates Kiefer and his activities but also because it animates us as agents of our own inquiries. For Kiefer, who has made books by hand since childhood, one virtue of a book is its ability to conceal: though it might explain the world, it does so one page at a time. That can make a book intimate and private. It also weakens the grip of linear time and the gravitational pull of a single, swiftly legible message. Kiefer’s handmade books, and his monumental lead-leaved books, are redolent of a bibliographic culture that is obsolete outside the field of artistic creativity: a culture of scriptoria, superseded philosophies, and protoscientific mysticism. In Kiefer’s works as in a library, esoteric or even defunct approaches to the world gain new possibilities—new life—precisely because the search for knowledge and the search for meaning are not always the same thing.

In his short story “The Library of Babel” (1941), Jorge Luis Borges describes the universe as a library of immeasurable scope, where countless hexagonal chambers hold regulation-length books that collectively include every possible permutation of characters from a limited alphabet.1 Inhabitants spend their lifetimes searching for meaningful texts among the volumes of complete nonsense. A handful strive in vain to eliminate the gibberish; others yearn for a messianic figure, the “Man of the Book,” who might have located a volume that holds the key to all the rest. The dream of unlimited knowledge rapidly becomes the nightmare of infinitesimal significance. Meaning, and those who seek it, are reduced to absurdity.

A true library is a model of creativity in process; an open work of collaborative art, regardless of who holds the key. A library with nothing to add is not a library at all.

Borges’s story is the foremost example of a topic that took form in the early years of modernism—in Kurd Lasswitz’s mathematically oriented story “Die Universalbibliothek” (The universal library, 1904), for example—and gained traction as an evocative metaphor for postmodern conceptions of how we use text and construct meaning.2 The labyrinthine, nearly inaccessible library at the heart of Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose (1980) owes a debt to Borges’s imaginary architecture, a debt that Eco repaid with the character Jorge of Burgos: the éminence grise of the abbey and its celebrated library, the “man of the book” who jealously conceals the sole extant copy of a work by Aristotle that deals with that most human topic, laughter.3

There is something profoundly inhuman, or at least inhumane, about the notion of an exhaustive library. It leaves no room for anything other than permutations of itself. As W. V. Quine pointed out in a playfully concise comment on the “melancholy fantasy” of a universal library, the universe—at least according to present estimates of its size—could only contain a small fraction of Borges’s library.4 Above all, an exhaustive library leaves no room for creativity: for the processes of defining, limiting, shaping, and reordering that meaning requires. A true library is a model of creativity in process; an open work of collaborative art, regardless of who holds the key. A library with nothing to add is not a library at all.

Eco’s best-known treatment of libraries may be The Name of the Rose, but he also made the mischievously creative use and misuse of libraries crucial to the plot of Baudolino (2000).5 Eco, a renowned semiologist and bibliophile with a sizeable personal library, treated scholarship as a creative performance that takes place in relation to books, among other phenomena, in a heuristic and nonlinear manner: a journey with neither a strict path nor a single destination. This view has particular relevance for the art of our time. In the late 1950s, he noted that the “open” situation of art, “far from being fully accounted for and catalogued, . . . deploys and poses problems in several dimensions.”6 Much of the appeal of libraries to contemporary artists rests on that recognition of openness, whether understood as a material or as a procedural fact. It is a sensibility that treats art as an ecological field of proliferating meanings, rather than as a catalogue of parts that assert themselves within a cogent whole. The behavior of things—including human participants—becomes more important than the status of things.

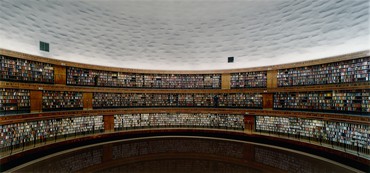

Our expectations of libraries tend toward classical aesthetics: wholeness, harmony, geometric balance, and symmetry. Modern libraries are, after all, descendants of an early-modern bibliographic tradition (Gabriel Naudé, who served as Cardinal Richelieu’s personal librarian, published Avis pour dresser une bibliothèque in 1627), and what we might call the mature style of library aesthetics took shape during the Enlightenment. Such libraries offer a reassuring glimpse of a diverse but ordered universe. Candida Höfer’s photographs of renowned libraries succeed not only because of her mastery of large-format composition but also because interiors such as the Long Room of the Old Library at Trinity College Dublin, or the now defunct Reading Room at the British Museum, integrate organic variety into architectural organization. As they adapt over time, such libraries develop a picturesque irregularity that translates wonderfully into two-dimensional detail. These full, rich collections of books arrayed in splendor can be hypnotic even as we begin to discern hints of underlying disorder. Andreas Gursky’s Bibliothek (Library, 1999), which shows the arcing bookcases of Gunnar Asplund’s innovative interwar design for the Stockholm library in all their expansive glory, artificially suppresses the rotunda’s ground floor and the mundane public self of the building. All we see is galleries of books with a couple of browsers who seem to be on the verge of dissolving into the bookcases.

In truth, library users are agents of disorder, liable to disrupt arrangements or—in a few instances—to disrupt the fabric of knowledge with publications of their own. Libraries do not come into being by fiat, but through the gradual unfolding of texts, commentary, contradictions, and elaborations. A veneer of rational arrangement conceals the sprawling, organic aggregation of ink and paper. Successful libraries are spatial and aesthetic triumphs over the piecemeal nature of material in space and time. They are composed, developed, and assembled according to rules that adapt to the material they ostensibly govern. In that respect, libraries are creative works that also behave in a creative manner.

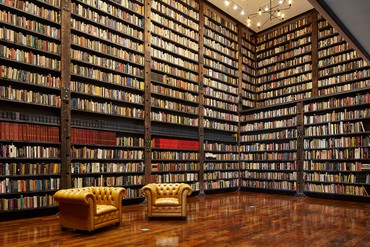

Large libraries conceal their sprawling connections behind depersonalized acquisitions and catalogues. Smaller libraries, particularly those in private hands, more easily retain their identities as tangible evidence of interests, tastes, or preoccupations. For a bibliophile such as Eco or Richard Prince, a personal library is simultaneously an extension of the self and a retreat into the self. Prince’s collection, which ranges from manuscripts by major postwar writers to pulp novels and ephemera from countercultural movements, also serves as inspiration, context, and source for his works and exhibitions. The centerpiece of his exhibition American Prayer, at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, in 2011, for example, was the series American/English, which presents American first editions alongside their British counterparts. The differences, often modest, reveal a great deal about how one society interprets another. Books contain not only printed marks but also encoded cultural symptoms that reveal values and points of view. As cultural artifacts, books encapsulate characteristics and behaviors that can spread as far as the books travel.

The role of behavior as a material in its own right, although crucial to open works of art of the kinds that have proliferated since the days of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines, remains difficult to assimilate into conventions of artistic judgment. The formal and disciplinary latitude that contemporary artists enjoy, however, provides considerable scope for situations or investigations that focus on the way we simultaneously conserve and exploit informative materials. In 2013, Theaster Gates bought a dilapidated neoclassical building in Chicago for one dollar. Gates and his Rebuild Foundation renovated the building, which originally belonged to the long-defunct Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank, and turned it into a library and archive called Stony Island Arts Bank. Along with books and periodicals, the Arts Bank includes sixty thousand lantern slides that once belonged to the University of Chicago; racist artifacts that a local banker accumulated in order to keep offensive stereotypes out of circulation; and four thousand vinyl records that belonged to Frankie Knuckles, a pioneer of Chicago house music, until his death in 2014.

Preserving superseded media and sensitive material is not merely an act of historical understanding and community service, but also an acknowledgment that historical understanding and community service require the tangibility of real places, real objects, and real encounters with places and things. Beyond that valuable service, however, Gates’s Arts Bank also shapes the intangible but heightened aesthetic consciousness that certain designated spaces—libraries, galleries, and museums in particular—engender through a blend of physical conditions and social conventions. In such places, we are predisposed to behave as aesthetically aware—and self-aware—participants in a cultural ritual. In that respect, the preexisting aesthetic culture of the library provides artists with an audience inclined toward certain ways of thinking and feeling.

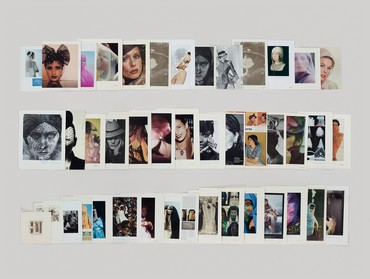

The possibility that works of art and those who engage with them can be conditioned, or even determined, by the aesthetic culture of the library is an intriguing aspect of Taryn Simon’s Picture Collection (2013). Simon delved into one of the more remarkable visual resources available to the public of New York City—the Picture Collection on the third floor of the New York Public Library—and made forty-four prints derived from a tiny fraction of the collection’s approximately twelve thousand subject folders. The folders contain all manner of prints, photographs, and ephemera that have reached the Picture Collection, sometimes uninvited, since its inception in 1915. As there is neither a firmly established taxonomy for images, nor an agreed-on method of cataloguing a collection with so many exceptions to so many rules, the Picture Collection developed its own idiosyncratic, ad hoc system to deal with the glut of pictures that came its way.

Joseph Cornell used to send material anonymously to the Picture Collection; Diego Rivera used its holdings while he was painting his unfinished mural Man at the Crossroads (1933, destroyed 1934); and Andy Warhol, who used the collection regularly, died in possession of a late-1940s Coca-Cola advertisement that he found in the folder “Advertising—Soft drinks.” These snippets of twentieth-century art history are intriguing for viewers who are conditioned by conventions of style and lineage to register connections among moments of inspiration. Similar moments are so thoroughly embedded in the nature of libraries, however, that we take for granted the diffuse nature of literary influence on writers and scholars. Simon’s project reveals, among its many other insights, the gulf that exists between our mastery of text and our confusion over images.

That confusion is partly a consequence of our faith in systems. Simon’s exploration of the Picture Collection shows how the dominant condition of organized information is not order but disorder; or, more precisely, the endless shaping and reshaping of whatever order we inherit. The way we assemble categories determines the way we assemble objects in space. That, in turn, guides the way we engage with those objects, how we think of them in relation to other objects, and how we use those objects to create new objects.

For the exhibition The Old Reading Room (1999), Ilya and Emilia Kabakov placed book cabinets and display cases laden with old books in the library of the University of Amsterdam. The cabinets and cases were arranged in an emulation of disorder and disregard, as though they had been declared obsolete, dragged into a seldom used room, and forgotten. A ventilation and lighting system made curtains flutter and the room seem to flicker as dramatic music played. The interplay of material objects and intangible forces dramatized a question that a text panel posed to visitors as they approached the room: “Is it possible that the computer has really conquered everything?”

When artists use libraries as sites, as scenarios, or as subject matter, they invoke our capacity to form an expanding set of associations for ourselves.

Around the turn of the millennium, the utopian fantasy of an unbounded library coalesced with the equally utopian assumption that high-technological systems offered an unprecedented level of transparency. The early years of mass Internet use prompted enthusiasm for dematerialized surrogates: hypertext instead of laborious cross-referencing; scanned copies of books, easily stored and distributed; ever expanding electronic storage in ever smaller physical objects; and decentralized terminals instead of buildings full of books. Perhaps El Lissitzky, who in 1923 used the term “electro-library” to encapsulate a drastic rethinking of the topography of the printed word, might have appreciated the capacity of technology to transcend—as he proposed—the spatiotemporal constraints of ink on paper.7 Whatever faith in the wonders of electronic dematerialization we might have had twenty years ago, however, has dwindled as our recognition of the Internet’s terminal indifference has increased. The realm of electronic storage and communication is a field of behavior, not an institution that takes shape. It lacks, much as Borges’s library lacks, the quality of mercy.

The communicative power of information technology gives us superb tools and poor surrogates. Its dedication to exactitude, and its reductive nature, remain at the level of a sophisticated but inherently amoral catalogue. Benjamin described his own library as “a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order,” and noted that “if there is a counterpart to the confusion of a library, it is the order of its catalogue.” He also offered a paraphrase of Anatole France’s view that basic information about the date and format of a book provides “the only exact knowledge there is.”8 That observation comes from France’s story “The Shirt” (1909), which describes a librarian who “lives catalogically,” happy in his completely unified ignorance and lack of self-awareness.9

When artists use libraries as sites, as scenarios, or as subject matter, they invoke our capacity to form an expanding set of associations for ourselves. As Simon’s Picture Collection demonstrates, libraries thrive on the kind of managed disorder that habit turns into an adequate system rather than a strictly logical one. Even the most rigorously ordered libraries remain what they always were: arenas for creative disobedience, dependent on refusal to accept that what we find is all there is. Whether we find ourselves within the porous, social exchanges that de Waal and Gates have established or outside Whiteread’s surrogates for unknowable and curtailed biographies, we intuitively grasp that “living catalogically” is a living death.

1Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel,” 1941, in Borges, Collected Fictions (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998), pp. 112–18.

2Kurd Lasswitz, “Die Universalbibliothek,” 1904, Eng. trans. in Clifton Fadiman, ed., Fantasia Mathematica (New York: Springer, 1997), pp. 237–43.

3Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose, 1980, Eng. trans. William Weaver (Wilmington, MA: Mariner, 2014).

4W. V. Quine, “Universal Library,” in Quiddities: An Intermittently Philosophical Dictionary (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), pp. 223–24.

5Eco, Baudolino, 2000, Eng. trans. William Weaver (Orlando, Austin, New York: Harcourt, a Harvest Book, 2003).

6Eco, “The Poetics of the Open Work,” in The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979), p. 65.

7El Lissitzky, “Topographie der typographie,” Merz, no. 4 (July 1923), p. 47.

8Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” 1931, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1968), p. 60.

9Anatole France, “The Shirt,” 1909, in The Seven Wives of Bluebeard and Other Marvellous Tales, trans. D. B. Stewart (London: John Lane, 1920), pp. 157–58.

Top to bottom: Kiefer: installation view, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Germany, 1991; artwork © Anselm Kiefer; photo: Will/ullstein bild via Getty Images. de Waal: © Edmund de Waal. Whiteread: photo: Urs Schweitzer, 2009, courtesy Imagno/Getty Images. Whiteread: © Rachel Whiteread; photo: Rob McKeever. Gursky: © 2019 Andreas Gursky/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Prince: artwork © Richard Prince; photo: Todd Eberle. Gates: © Theaster Gates; photo: Tom Harris, courtesy Rebuild Foundation. Simon: © Taryn Simon