Brooke C. Obie is a screenwriter for TV and film, the award-winning author of the Black-revolution novel Book of Addis: Cradled Embers, and an award-winning film journalist. She is the editor-in-chief of Will Packer Media’s Black-women’s lifestyle site xoNecole. In 2019, she was named to the Root 100 Most Influential African Americans in the media category.

In the wake of a global pandemic, the Bahamian artist Gio Swaby is living in the extremes. From the grief of losing her mother at the height of COVID to the elation of watching her seven nieces and nephews grow and think and be via FaceTime, Swaby is dealing with the intense emotional extremes of the world’s new normal with her own secret weapon: Animal Crossing.

This social-simulation Nintendo video game is Swaby’s favorite way to go “outside” these days as the pandemic rages on in Toronto, where she lives, keeping her away from family and her beloved Bahamas. Still, with so many people stuck at home but more accessible in other ways, Swaby has found herself closer to her family than ever. It’s no wonder themes of finding play, connection, and joy in the midst of tragedy remain constant in her art: it’s just the way she lives her life.

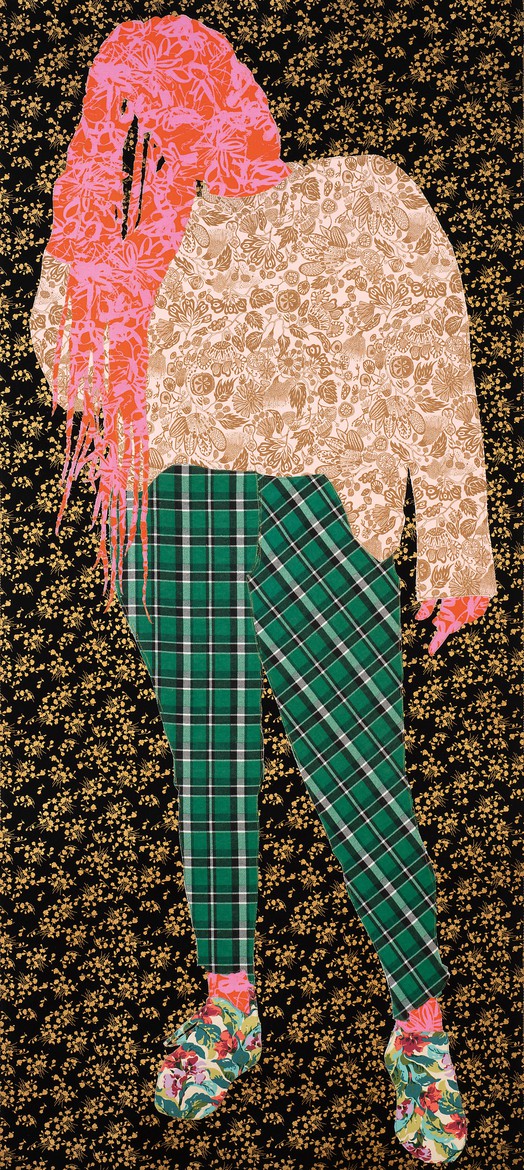

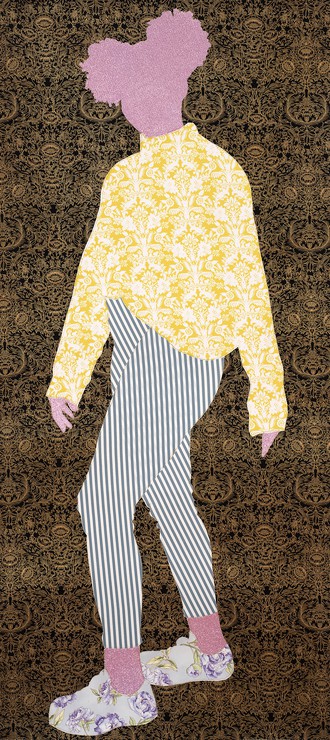

A recent iteration of this twenty-nine-year-old artist’s life and mission was her debut solo exhibition of mixed-media art, Both Sides of the Sun, at New York’s Claire Oliver Gallery from April to June 2021. A play on psychologist Dr. David Viscott’s saying “To love and be loved is to feel the sun from both sides,” Swaby’s show featured over twenty new pieces—what she calls “love letters to Black women”—displaying the fullness of Black womanhood in mixed-media textiles and life-size threaded line works. The Pretty Pretty series, for example, is a collection of swagged-out, full-bodied Black women rocking Afro puffs, plaits, natural updos, and headwraps, all made from fabric and thread stitched into canvas. A pop of color in each piece lies in a woman’s belt or combat boots, a patterned fabric that spans the length of a pant leg or the lining of a kimono. In Swaby’s hands, Black women on canvas are the baddest in the game, striking their poses—a hand in the air or on a hip—with unmitigated confidence and irrevocable beauty.

This series marks a “breakthrough” in her artistry, Swaby tells me over Google Hangouts, as it shows new depths in both her skill with a needle and fabric and her willingness to be exposed with her viewers. “It has stitching for the line work, but the side that’s displayed is what’s technically the back of it,” she says. “So that marks a special shift in how I’m thinking about my work. I create this portrait on one side and then the side I’m revealing [to the viewer] is the side that’s normally hidden, to be able to share this moment of vulnerability with the viewer, to have them be able to map the process of How did I make this?” With threads hanging from her pieces in this series, she fully embraces a path of self-love through acceptance and the celebration of imperfection.

While Swaby’s line work may now be visible to the viewer, it’s still difficult to fathom her talent of encapsulating lifetimes of Black women in a single piece of art. Take her Love Letters series in the same show. These portraits of Black women in Bantu knots, fades, and natural updos are also made in fabric and thread stitched onto canvas, but the women are featureless, the outlines of their heads and necks filled with quilted flower and geometric patterns that feel simultaneously ancestral and modern, giving the women the ability to represent all the women in their lineage who came before them, as well as their present selves.

“That idea of an exploration of ancestry . . . that’s what a lot of the work is for me,” Swaby tells me. “I don’t have a good grasp on my own ancestral history because of slavery, and being from the Caribbean, too, record keeping is tenuous—for anything even 100 years ago, it’s difficult to find records. My artmaking was a way to connect to that, to explore my ancestry through visual aesthetics—the way I look, through hair care and hair styling, too,” she says. “I see it as an exploration of self, but also like a celebration of a lifetime of being supported and uplifted by Black women. It feels like a really great honor to do that.”

It’s not just Swaby’s unknown ancestors that she is tapping into when her needle meets a canvas, but also her late mother. A seamstress in the Bahamas, Swaby’s mother, Judy Carey Swaby, was always sewing school uniforms for students, and Swaby would help her as a child, sewing buttons and hooks onto skirts. “It’s never really been easy for me within my family, verbally expressing affection and love to one another, but that action of us connecting to one another, through sewing and making things together, really was an act of love between us,” she says.

Still, although Swaby was always creative, she never imagined making a living as an artist. In those days the self-described “black sheep” of her family dreamed of being a pediatrician. Only when she started the fine-arts program at the University of the Bahamas, in 2009, did she truly feel that art was not only her calling but a career she could pursue with both hands and a full heart. She jokes that her villain origin story could have begun around this time when, surrounded by family at her birthday party, she announced that she was studying art and planned to be a full-time artist—much to the dismay of her older family members, who did not see art as a viable future. “That doesn’t make sense!” they told her. How would she ever make a decent living as an artist? The response was so shocking and devastating for Swaby that she briefly excused herself from her party. No one in her family or immediate vicinity was an artist; she had no intimate example or path to follow. But she felt content to let her heart take the lead. “I just cried in the bathroom and shook it off,” she says of that night, and became more determined than ever to perfect her craft.

During a residency at Popop Studios in Nassau, Bahamas, Swaby met the quilter Jan Elliott, learned free-motion sewing—a technique where the feed dog of the sewing machine is disengaged, so that the sewer has control over where the needle moves—and immediately felt connected to the method. “That’s one of the times in my life I can identify a specific point when I felt like I was supposed to do this or this was supposed to happen,” she says. “I saw it as so many different parts of my life connecting, like being able to connect my background in sewing to my art practice, back to my family and then also to this idea of community and quilting. It was really exciting to see this way of using thread to draw. I’m a person who can become quite obsessive, and that was one of the things I fixated on, trying to figure out, How can I build on this technique and where can I go with it?”

I talk a lot about the work being about joy, but you find that joy through healing. The work I’m making does not disregard that trauma; it’s thinking about how we can heal. For me, finding joy is a way to do that.

Gio Swaby

While the Caribbean’s history of slavery has distorted more-specific ancestral connections for Swaby, she still incorporates the passed-down knowledge of her forebears into her art. Like the mishmash of fabrics in her pieces, Bahamian identity comprises not only the African peoples enslaved on the islands but also the indigenous Lucayan people, the first people Christopher Columbus encountered—and enslaved—in the Caribbean. The Lucayans, Swaby says, “are described as very peaceful people, and docile; because of that, instead of taking that as a sense of kindness, [Columbus] saw it as a way to easily make them into slaves. They were almost completely wiped out.” The Lucayans live on in present-day Bahamians, who can also trace their family histories back to specific islands in the archipelago by their surnames. “My mother’s side of the family comes from an island called Eleuthera,” Swaby says. “We even know down to the settlement, Tarpum Bay, because our people still live there—my great-aunts and -uncles—and we still visit. It is the closest thing to an ancestral land I can identify.”

These topics of tracing Black Diaspora ancestry after the violence of slavery, and exploring Black women’s hair and hair care in an anti-Black, white-supremacist world that polices and criminalizes our hair, can be triggering and traumatizing to revisit in art. But in Swaby’s lens, the focus is always on the unbreakable connections and intricate beauty of Black hair traditions. In resisting the master narrative of Blackness in her practice, she finds, as Alice Walker said in her 1992 novel Possessing the Secret of Joy, that very secret. “So much of my work is about paying tribute to the women I’m representing, and immortalizing not just them but other Black women and girls who see themselves in the work,” Swaby says. “I have goose bumps right now just thinking about it because the most important, most humbling part of what I’m doing is making those connections, representing us in a way that’s full of personality, full of character, full of personhood—especially when historically we’ve been very excluded in that respect.”

Swaby goes on to observe, “So much of that is removed in representations of Black people because it wasn’t other Black people creating that artwork. We’re bombarded with images of Black people suffering and experiencing trauma. It affects you; it takes a toll to see it over and over again.” Aware of the traumatic elements that her art touches upon, she insists that trauma isn’t the only legacy in our lineage. “That’s at the crux of what I’m doing,” she says. “I talk a lot about the work being about joy, but you find that joy through healing. The work I’m making does not disregard that trauma; it’s thinking about how we can heal,” she says. “For me, finding joy is a way to do that.”

Every image of elated Blackness that Swaby puts into the world is a conjuring of Black joy, not just for herself and her practice but also for the viewer. “My artwork is contributing to my healing from a lifetime of being indoctrinated into very anti-Black ideologies, and also healing from perpetuating that myself,” she says. “I’m also hoping to create that moment, once the work is finished: someone sees it and interacts with it to create that moment, and feels a sense of being seen and feels that joy.” In that joy, Swaby also aims to create for her Black audience a collective experience of reprieve from the burden of anti-Blackness by seeing ourselves reflected through her lens of love. “When I’m making my work, I’m thinking about creating a space of community, creating a moment of relief—just a moment of relief—when you can enter that space and feel a sense of being able to be at rest for just a moment with this work,” she says.

Swaby’s work is both in the resistance tradition of iconic interdisciplinary artist and quilter Faith Ringgold and in conversation with that tradition. From her earliest works of the 1950s, Ringgold’s art reflects her experiences and struggles as a Black woman growing up during the Harlem Renaissance, the civil rights movement, and the women’s movement—with all of the terror and joy that entailed. Swaby’s quilts talk back to the story quilts that Ringgold began to make in the 1980s, snapshotting life for young Black women in the new millennium. “I’m always supergrateful to the people who have come before me and have already made these pathways for me to be able to make the work I’m making now,” Swaby says. “I feel like I have a community of support; I’m a part of the conversation about reframing existence for Black people and what that can look like, and also the conversation about futurism: what do we see happening for us and how can we make that happen?”

As for what’s next for Swaby and her art, there is no limit. “I almost could see anything in my future,” she says without hesitation. Fans of her Pretty Pretty series have asked whether the shoes and clothes she’s designed and drawn by hand, with thread, are available for purchase, and while she’s not quite ready yet to be a fashion designer, she wouldn’t count it out. “I just love learning,” Swaby says. “I love that experience of just being open to always learning and doing new things.” That boldness and willingness to take risks come from her father, who passed away in 2016. “My dad said, shortly before he passed, that he was happy because he got to live his life. He wasn’t old, he was sixty years old. I took some of his principles of living,” she says, because “as far as I know, I only get this one life here. And what am I doing if I spend the whole time working or worrying?”

These days, Swaby is enjoying Tricia Hersey’s Nap Ministry, a social-media platform where Hersey preaches naps and rest for Black women as an act of resistance. Swaby is finding her rest on the couch, watching her favorite TV shows—Michaela Coel’s Chewing Gum and the Netflix comedy series Sex Education and Special. Issa Rae’s Insecure is also a source of inspiration for her: “I can’t identify a specific moment, but the way that show is lit for Black skin, I just get so much feeling like, This is incredible. I want to see how I can re-create that same feeling within my work.” She adds, “That idea of being able to be imperfect is revolutionary to me.”

Swaby’s biggest source of joy remains her home country, the Bahamas. Until she can make it back there, she dreams of the food she will eat immediately upon her return. “I have to do guava duff, a Bahamian dessert, and a conch salad,” she says. “I have to get a fried-fish dinner that has to be nice; if it’s not nice, it don’t really count.” (“Nice,” to Swaby, means superseasoned and fried “dry, dry, dry,” so it’s extra crispy.) To Swaby, food is also art, is also joy.

Swaby may be living in the extremes, but by doing so, she elucidates the fullness of joy. Black joy is bigger than survival; it’s expansive enough to hold the depths of ancestral grief and triumph. Black joy is an inherited behavior, a dedicated practice, and a daily commitment, to self and each other, to keep showing up—seams showing, threads hanging down—and choosing life.

“Black to Black” also includes: “How to Collect Art” by Roxane Gay; “Leaps of Faith: A Conversation With Jordan Casteel and Calida Rawles”; “Commemorative Acts: Ladi’Sasha Jones” by Ladi’Sasha Jones; Kellie Romany: Many Bodies Corralled; “Visual Abundance In The Work of Kezia Harrell” by Randa Jarrar; and “A Body of Work: Firelei Báez and Tschabalala Self” by Amber J. Phillips