Ladi’Sasha Jones is a writer and curator from Harlem, New York. Her research-based practice explores Black cultural and spatial histories through text, design, and public programming. She is currently a PhD student in architecture at Princeton University.

My introduction to archives began during a summer break between college semesters. I attended a public program at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem, New York, around the burgeoning In the Life collection and left that evening with an internship in the library’s Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books division. I spent the summer going through the unprocessed papers of Black feminist poet Cheryl Clarke, whose work I knew well and greatly admired. Walking up Lenox Avenue to 135th Street to make my way through the boxes and folders of Clarke’s writings, community-organizing documents, and letters, carefully studying each piece of paper and ephemera, became a practice I fell in love with. This intimate engagement with the archive of a Black woman artist offered me a great deal of learning around research and storytelling as unfolding acts of change. Clarke’s collection taught me how to look closely and slowly; how to annotate findings and develop strategies for note-taking; and how to map time and the measures of collaboration. That summer, I experienced not only archives as sites for preservation and data collection but the practice of archiving as an artistic device that transmits values around determined narratives and knowledge systems.

There is art in telling one’s story, any story, through the cumulative process of storing associative files, images, and objects. Consider the emergence of poetry across an assembly of records. Consider the subjective shadows distilled from organized marks on preserved paper. Consider the art of record-keeping and documentation, of collecting and holding on to the cultural materials that reflect the qualities of a life, a community, a place, a movement. Now consider the shared ground between the archive and collage: both invite the emergence of new interpretive meanings and connections from collected materials. Although at times didactic, the archive can appear as a multitude of abstract matter. Similarly, collagists assemble media fragments or objects across time and space to signal a storyline or a new imagining. A whole new entity is made from a cumulative process. We know that Black women’s histories have been historically submerged or relegated to the periphery, if present at all, within archival repositories. Traditionally, local and communal sources of record-keeping have sustained our stories. However, many contemporary artists are using collage to remap these power constructs and address the social fields of community-building and storytelling.

The archive is a site where tactile conditions of intimacy not only exist but matter.

Visceral assertions around body politics appear across the works of several Black women collagists. We can trace the scaled messaging embodied in cutouts of an arm, a lip, or a slick hairdo, but what surfaces for me is the buoyant logic or sensibility of rebellion that is often present in figurative narratives across this visual medium—for example, the works of Wangechi Mutu. Mutu’s daring figures are positioned in environments that are otherworldly or exist beyond this one. They trouble and dance wildly in the spatial holds of the feminine, referencing the fragility of the postcolonial and its violent impacts on the environment. In Non, je ne regrette rien (2007), Mutu’s characters are not averse to risky behaviors or to dwelling in a space of transmogrification. Once upon a time she said, I’m not afraid and her enemies began to fear her The End (2013) features a creature made up of earthy, cellular, and industrial parts, walking across a jagged landscape and marking its travel by leaving nondescript splats or pollutants in the air as it moves along. This figure, like many of Mutu’s characters, is both an actor and a keeper of consequence. In reflecting on Mutu’s work I find myself recalling Jamaica Kincaid’s famous short story Girl (1992). The story is structured as a single sentence, an elongated breath of instructions for coming of age into womanhood. I believe Mutu’s intransigent figures, like those that stand tall in her sculpture series Sentinel (2018– ), would easily dispel the warnings or expectations toward tradition offered in Kincaid’s story as they are en route to remaking and contorting the world in their own image.

What blooms in the space of self-imaging? Does power bloom? World-building?

Lorna Simpson has an enduring engagement with figuring Black women subjects. Art historian Huey Copeland writes that Simpson’s practice “has consistently worried over the status of the body and the consequences of its divergent modes of self-perception for the constitution of the black female subject.”1 This is definitely true of the playful yet poignant gestures in her early photographic works, and of her popular Jet (2012–18) and Ebony (2014– ) series of collages. The popular images of Black women that scored the pages of those periodicals are also the source material for works in the Earth and Sky series (2016– ), which pairs cutouts of models with raw materials and gems that crown their heads. Similarly, Speechless (2017), from the Ebony series, features a black-and-white cutout of a model’s face with scrambled letters crowning her head. Simpson’s video work Animations (2016) features a more speculative activation of these serial collages, wherein a model is suspended on a billboard plank amid a sky of shifting clouds, while gray puffs billow from the headspace of another. The piece seems to situate these collages in an extended narrative that transmogrifies the subjects into allusive glitches. These subjects are not mere specular beings, they are performing critical acts of fissure as they are remade and refashioned apart from the folds of a magazine.

Deborah Roberts’s portrayals of Black children are also constructed in a space of associative glitches, yet are projected as sublime motifs. Her figures are posed in a void, where the surrounding scene is absent or to be imagined over the blank horizon. Black children occupy public space and are hypervisible yet self-possessed. Roberts works with the intention of collecting pictorial references that close the dissonant gap between their ages and the sliver of innocence that is extended to them by publics, institutions, and legal authorities. In Let Them Be Children (2018) and Between Them (2019), she renders the figures with an interior quality that is not typically relayed in representations of Black youth. The children are posed with humor and fragility. There is also an air of leisure and coolness in their assembly. Across these works, Roberts is depicting what many of us already know to be true, and that is that our children are the gatekeepers of Black cool. Still, a prevailing overtone amidst the dramatic flares of coolness reminds us that the figures are indeed children. They are young people whom we are charged with nurturing and protecting at all costs, as their safety is a measure not only of our contemporaneity but of our futurity.

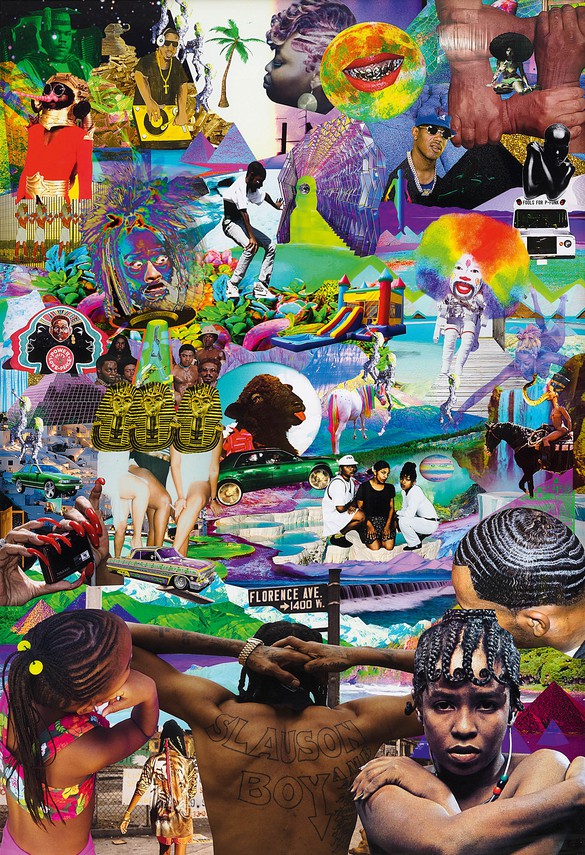

In alignment with expressions of Black cool, the aesthetics of funk color the practices of Lauren Halsey and Xenobia Bailey. Their work proposes how one can take direct action through the material space of textiles and the built environment. Through architectural approaches, Halsey’s sculptural and graphic compositions are developed in direct response to her home place of Los Angeles. The mixed-media installations we still here, there (2018) and My Touch (2020), alongside the digital collage gotta get over the hump? (2010), are great examples of how she assembles found objects and a range of LA-based retail iconography to shape a body of work that volumizes the hyperlocal. Halsey’s gypsum installations are monumental gestures to honor her environmental context. They are striking exercises in self-historicization that are deeply tied to larger motivations around caring for Black urban and communal space: “No matter the context, I’m always thinking about what returns and gets redistributed to my neighborhood. There’s always a community ethos. I don’t see art and architecture as separate from the community. They’re sort of a cause and effect.”2 Halsey’s concern with local redistribution has grown into a social practice of place-making through the building of the Summaeverythang Community Center in South Central, which has taken on the service of reimagining organic foodways for her community.

Where Halsey’s work tackles city and communal formations, Bailey’s mandala tapestries pull us inward to reflect on the funktional work of the Black homemaker. Much of her work bends toward projects that are shaped around histories of Black self-built and handmade designs. Motifs of world-building are sketched across her fabric pieces, such as Sistah Paradise Great Wall of Fire Revival Tent Mandela: cosmic tapestry of energy flow (1999) whose larger narrative involves a uniform and tools for the folk character “Sistah Paradise.” Both artists directly communicate their love, a deep love, for Black folks. Their visual geographies inhabit the multifarious vernaculars of Black social life and cultural production through bright neon colors, dense repetition of patterns, lo-fi architectural constructions, bold typography, and surrealist design.

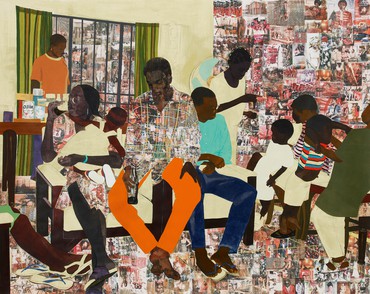

For me, the archive is a site where tactile conditions of intimacy not only exist but matter. Like Bailey, Billie Zangewa creates tapestries based on quotidian scenes of home life and the familial. Zangewa began her practice reproducing cityscapes before shifting her gaze to the domestic space. Many pieces center acts of solitude, moments of aloneness that are hand-stitched across silk collages such as Afternoon Delight IV (2018) and In My Solitude (2018). There are also scenes that feature multiple figures, akin to the collage-based photo works of Njideka Akunyili Crosby, who focuses on domestic convenings of friends and family, the companionship between lovers, or the twinkling capture of a table set for teatime. In 5 Umezebi St., New Haven, Enugu (2012) a group of people, ranging from children to adults, are positioned across the composition with lots of motion and energy, evoking a lively family gathering full of play, discussion, and caretaking. Her interiors are autobiographical studies of Nigeria past and present, as depicted through the styling of garments, room settings, furniture, and the placement of products. They are constructed from composites of xeroxed popular imagery, family archives of photographs, and other sources that add depth to the textures and a sense of time or rhythm to the works. Looking at art by Zangewa and Akunyili Crosby during this time of isolation and calculated public engagement during the pandemic reminds me of the lush garden of togetherness we have gone without over the past two years. Works by both artists spark longing memories of homes filled with many bodies, voices, and smells. To be in a crowded living room or hallway surrounded by aunts and cousins. To ascend a flight of stairs and reach a pair of open arms awaiting to embrace you as loving words sing-song between your ear and cheek. These sites of home and kinship are sprawled across both of their bodies of work, illustrating that we are very much alive, both at home and in public, when alone and in the fellowship of others.

There is art in telling one’s story, any story, through the cumulative process of storing associative files, images, and objects.

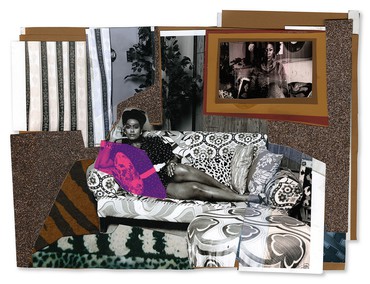

The installation and collage work of Mickalene Thomas digs further into the aesthetic qualities of interior domesticity, not only as a social setting but as a site for the stylized fashioning of the Black home. The living room and spatial designs in Clarivel #5 (2014) and Interior Wicker Red Chair Leopard Rug And Candles (2015) are filled with wood-grain paneling, mirrors and reflective surfaces, florals and cross-checked and paisley patterning on the curtains and sofas, and often a floating view to the outside. The atmospheres are warm and fully dense, far away from minimalist principles. Seemingly depicting scenes before a party or a gathering of sorts, they convey homes that are active. Homes that collect things, from a scattered library to hangings on the wall. Homes that transform constantly as they are lived in year round. Homes adorned with cultural aesthetics as a site for recovery from the outside world.

One can trace similar elements of aliveness from the archival world-building within Thomas’s living room sites to the playful engagement in Martine Syms’s Web-art piece EverythingIveEverWantedtoKnow.com (2007). Despite its digital form, this work can surely be written into this conversation of an archival, even research-driven engagement with collage. The piece presents a multiyear index of Google searches, illustrating the digital questions, information exchanges, and data collection that shape so much of our relationship to the Internet and modes of knowledge production. This cheeky, nonchronological assembly of queries directly positions the index as a tool of record management and a form of collage—a gestural data performance or exploratory exercise on user profiling, privacy, and consumption.

The affects of archival transmission and circulation materialize within this piece by Syms and across the collage works of Mutu, Simpson, Roberts, Halsey, Bailey, and Thomas. Framed as speculative archival acts that commemorate Black quotidian life, imaginings, and space, their record-keeping and spatial constructions connect to the archival efficacy I encountered within Clarke’s papers many years ago. A visual language is being marked, one that strategically considers the unfixed workings of memory and interiority. These artists rigorously empower a compositional sublime of Black thought and media, alongside the wild potential of love and change.

1Huey Copeland, “‘Bye, Bye Black Girl’: Lorna Simpson’s Figurative Retreat,” Art Journal 64, no. 2 (Summer, 2005): p. 74.

2Lauren Halsey, in “The Art of Community,” a conversation with Alice Grandoit-Šutka and Isabel Flower, deem, n.d. Available online at https://www.deemjournal.com/stories/lauren-halsey (accessed August 26, 2022).

“Black to Black” also includes: “How to Collect Art” by Roxane Gay; “The Root of Black Joy: The Work of Bahamian Artist Gio Swaby” by Brooke C. Obie; “Leaps of Faith: A Conversation With Jordan Casteel and Calida Rawles”; Kellie Romany: Many Bodies Corralled; “Visual Abundance In The Work of Kezia Harrell” by Randa Jarrar; and “A Body of Work: Firelei Báez and Tschabalala Self” by Amber J. Phillips