Amber J. Phillips is a storyteller, filmmaker, and creative director. She creates world-building narratives using warm visuals and vulnerable performances through the lens of a fat Black queer femme auntie from the Midwest. Phillips recently released her first short film, Abundance, which was a 2021 BlackStar Film Festival selection and won the audience award for Best Short Narrative.

One of my favorite self-care practices is to take myself on solo dates to experience something I’ve never seen or felt before. I’ve learned that when it comes to developing a taste, you must have a wide range of experiences to create a deep-rooted sense of what you like. And I have a taste, a hunger, rather, for art and culture created by Black people, women, and queer folks. Knowing as much as possible about us is my greatest pleasure.

Unfortunately, capitalism routinely creates barriers to discovering what brings us pleasure. These barriers are masterfully constructed around the experience of visual art—even when the art is specifically created with someone like me in mind. I learned this the first time I took myself on a date to visit the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC.

At the time, I was living in DC, and the Portrait Gallery was a straight-shot bus ride from my apartment in Columbia Heights. Young teenage Amber was right: there was a world beyond going to church several times a week, Ohio State football, and excellent ice cream. Now I could visit critically acclaimed art on a casual Saturday morning. On this morning, I ventured into downtown DC specifically for Robert McCurdy’s photorealist oil painting of the beloved writer and fellow Ohioan Toni Morrison and the recently hung portrait of former President Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley.

The portrait of Obama is surrounded by other works, but it’s clear who the main attraction is, given the line of people waiting to see the piece. Normally I’d be deterred by a queue of mostly white people, especially pre-COVID. But I wanted to stare at Wiley’s chrysanthemums, jasmine, and African blue lilies without any heads interrupting my sight line. I don’t believe I’d looked for a full ninety seconds before I was directed to “keep moving” so more people could see the flowers. Slightly annoyed but still delighted to be in the building with these images, I perused the gallery on my way to see the painting of Morrison. I suppose I was leaning too far in, challenging my eyes to identify the paint strokes that made up McCurdy’s hyperrealistic rendering of one of the greatest Black American writers of my lifetime. It didn’t take long before a man wearing a cheap imitation of a cop uniform asked me to take a step back.

In this moment, I realized I was most likely being closely watched the entire time I was at the gallery. I was there alone, big and Black. I was well dressed for my version of a day out in DC, but not as your typical DC tourist or patron of the arts. I think my Hyper Violet–and-black Air Jordan 12s gave me away. The experience left me feeling like I didn’t belong, despite visiting exhibits that felt like they already belonged to me. I wanted to be there not only to see the work but to learn its history and context.

Before Wiley painted Obama, he had an exhibition in my hometown of Columbus, Ohio, titled Kehinde Wiley: Columbus (2006). I was fifteen years old and visited the Columbus Museum of Art on a field trip with my art-focused after-school program. Somewhere in the world is an old hot-pink Motorola Razr with a picture of me standing in front of Wiley’s Portrait of Andries Stilte II (2006), mimicking the pose. When you’re a kid in a museum, everyone talks to you. You’re there to learn and people want to share what they know with you. I remember watching a short video on display in the gallery that showed Kehinde driving around Columbus looking for subjects to paint. The Black men in these larger-than-life vibrant images were my neighbors. I never forgot how it felt to see someone imagine us bigger than our circumstances.

Where we discover new art, how we are treated in those moments of discovery is as important as the art itself. And of course, existing in a Black body, and how my body is perceived, also determine my level of ease in navigating within art institutions. Unearthing the work of Firelei Báez and Tschabalala Self during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown made me feel how I imagine the Black men in Kehinde’s paintings must have felt seeing themselves honored in their XXXL white T-shirts and Lugz boots in 2006.

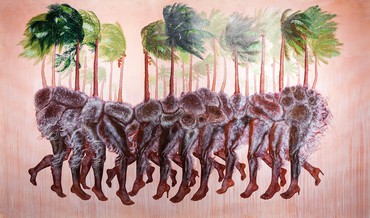

As a fat queer Black femme, I live outside the illusion of patriarchal safety because of my gender while also being routinely denied access to the myth of femininity because of my race. Although Báez is constantly referred to as an artist who paints the “female form,” her paintings entirely obliterate the restrictive nature of identity. Visually deconstructing gender, she offers us a stunning mystical image of Black, Brown, and Indigenous embodiment through her depiction of Ciguapas, magical creatures fabled to haunt the mountains of the Dominican Republic. Ciguapa Pantera (to all the goods and pleasure of this world) (2015) depicts an almost-human life form covered in brown fur and adorned in a crown of tropical plants. This enchanting personification of creatures and land is also on full display in How to Slip Out of Your Body Quietly (2018). In the painting we see multiple Ciguapas unfolding into a vast forest. A wind is painted into the tossed branches of the palm trees and the gust seems to be coming from the movement of the Ciguapas instead of their environment. Báez’s depiction of slipping out of a body as a means of duplication and expansion. This lands as a specific nod to the innate abundance of Black and Brown people and our legacy of self-discovery as a means for growth and cultural wealth.

In an early-morning Zoom interview with Báez, I asked her how she views gender in her life and in the worlds she is creating with the Ciguapas.1 She shared that “I was always aware of gender even as a young child, and I wanted to find a slippage. In the slippage you get to understand how everything is a construct. In romance languages (Spanish, French, Italian, etc.), they always have very clear gender in everything. Along with that gendering, nature is also gendered female. And when you gender something female in those languages, you predicate it as passive. A tool for use. Ciguapas are not actually gendered. They aren’t women and they aren’t men. They are something unto themselves.”

As an artist of Dominican and Haitian heritage using the folklore of the Ciguapa, Báez shows us how to mine our specific cultural history in order to envision the possibilities of gender, race, and geography.

I find Báez’s paintings remarkable and incredibly moving. I pray to be able to see her work in person one day; so far I have only seen it online, where I tend to view it full screen, so that I can get as close as possible. Being nose-to-nose with her pieces, even virtually, helps me wrap my mind around the easeful precision in her bold, colorful strokes—as if jumping inside her pieces will help me better understand the question I’m constantly asking of artists I’m learning to love: “How did they do that?!” In speaking with Báez, she gave me something more powerful than simply telling me how she creates her work, instead recalling a notable Toni Morrison quote: “The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” Our shared knowledge of Morrison confirmed that Báez’s work is meant to be interrupted by people like me who may not know everything about art and art history but love the work and the people whose stories are being told. Báez paints inside of the being Morrison speaks about.

In the summer of 2021, Báez opened her biggest exhibition to date, an immersive sculptural installation at the ICA Watershed, Boston, that is her manifestation of the ruins of the Sans-Souci Palace in Haiti. A mural featuring a Ciguapa welcomed guests into the massive show, the scale of which gave her audience space to be enthralled by stories of migrant histories. The visitor stood in an open space, enclosed by indigo materials that served as signifiers of both shelter and disaster. Once you accepted the invitation to be submerged in the experience, there was no way to be too close to the work or to be rushed along.

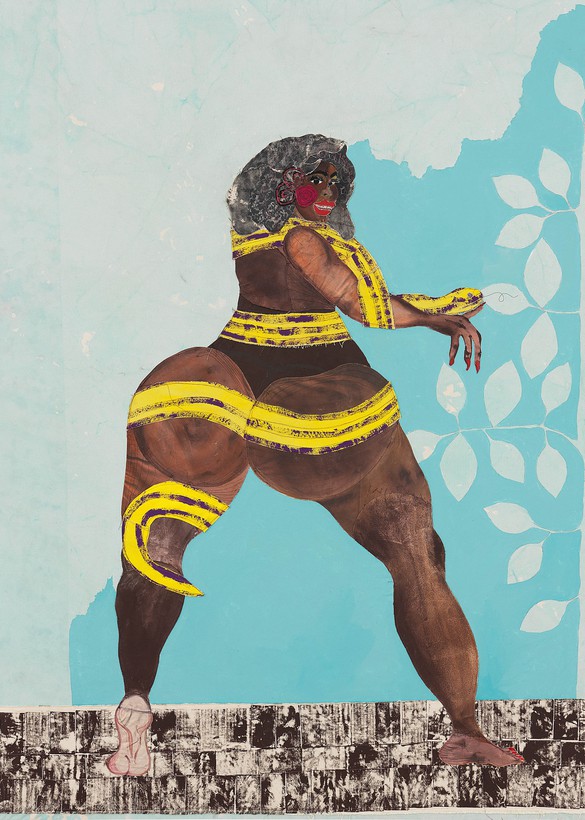

Most days, I’m not sure whether it’s intentionally whimsical or aggressively absurd to believe that art is an effective tool of liberation. This is especially relevant when artists are in on the fact that they are amplifying what they love. Like Báez, Tschabalala Self unravels and mends our incomplete understanding of Black bodies and gender performance. Her mixed-media painting Evening (2019) is almost as tall as my five-foot-eleven-inch frame, and feels familiar. The figures are large and exaggerated in a way that feels not like a caricature of a big Black femme body but like an appreciation of one. Even Milk Chocolate (2017) feels quotidian and reads as a reclamation of the title phrase, which has been forced on me, a darker-skinned Black femme, as a compliment. Self is in on the experience of navigating the world in a Black femme body and offers a nod of solidarity to others like her.

We aren’t just holding up a mirror to ourselves and our communities; we are building the mirror. We are teaching people how to see us and make space for what they see.

Self has said that her muses are “America, Black America, Black Americans—Black individuals in general.”2 She rejects the assumption that the Black bodies in her work are “distorted” or “enlarged,” saying instead that they are scaled to her body and the bodies of Black folks with whom she is in community. Self’s images make me feel alluring and worthy of being placed on a pedestal of protection. I would love to know what it feels like for someone other than a low-budget imitation cop to tell people to back up if they get too close to me. And please make them stand in a line and stop staring when I’ve had enough. Out of context, all Black people can seem bigger than average, especially when we are separated from our communities. I’m sure Self’s work will seem huge against the white walls common in galleries until an equally huge Black body shows up in that space. Out of Body (2015) visualizes the ambivalence of the way we Black femmes view ourselves in relation to how other people take in our image. She calls into question the idea of realism when applied to a group of people whose entire existence has been violently distorted by the white patriarchal gaze. Our work to right this wrong through our own interruption is being measured against old tropes that we never created to begin with.

Poet, essayist, and cultural strategist Aurielle Marie chose Self’s work Nate the Snake (2020) as the cover art for their recently released poetry collection Gumbo Ya Ya. As a fat, Black, queer, Southern, and Disabled person, Marie is also contending with the limits of Black identity and gender in her work, specifically in the arena of language and storytelling. Talking about where her creative writing aligns with Self’s art, Marie told me, “Anytime I talk about girls I spell it with an ‘x’ instead of an ‘i’ as a way of noting my being as genderqueer, but Black folks are also genderqueer. Black folks are very counterculture in the ways we navigate gender, because of race. I was looking for something very gaudy and offensive to anyone who, as my grandmother would say, has a sensitive or demure palate. I wanted the image to be something confrontational because Gumbo Ya Ya is a confrontational text.”3

Both Self and Marie are creating in a way that allows them to set the standard by which their art is consumed and interpreted. Most Black women, femmes, and nonbinary artists aren’t only making their work, they also have to actively create their own context. We aren’t just holding up a mirror to ourselves and our communities; we are building the mirror. We are teaching people how to see us and make space for what they see.

In January 2019, wanting to give myself permission to fully commit to being a writer and storyteller, I accepted a Civic Media Fellowship with the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California. Moving away from the comfort I had built for myself in DC to relocate to LA has been the biggest self-care experience I’ve given myself to date. My plan was to experience and learn as much as possible about the art that is globally distributed out of the cultural center that is Los Angeles.

By March 2020, though, I found myself quarantined in my apartment, away from most of my friends and family during my first viral pandemic. In addition to the omnipresent fear of becoming sick and unbearably lonely, I was forced to reckon with not being able to adventure through the art galleries and museums in my new city. Turns out I wasn’t alone in processing how to access joy and imagination during a pandemic. The temporary closures of cultural institutions did not stop the curation and making of art; it made both more accessible. Conversations between established and emerging curators and artists were broadcast live on YouTube and Instagram. Some galleries even allowed viewers to join Zooms where we could ask our questions directly to emerging, new-to-me voices such as Bisa Butler and Kennedi Carter. Formerly inaccessible cultural experiences became accessible from the comfort of my own home. I was able to experience visual art as something that could come to me. I was able to take in art in a completely new way that wasn’t just among white walls in hushed tones. I finally gave myself the permission to learn about art in a comfortable setting where only my gaze mattered. During one of the most isolating years of my life, I found joy by recommitting myself to an old love in a new way.

As we move forward with collectively creating our new normal in an ongoing pandemic, my hope is that the new environments I enter and the ones that I return to will hold me with as much care as I have held myself. In this aftermath, we must be serious about imagining a more abundant experience for witnessing and creating art. As Báez shared with me during our conversation, we should all be asking ourselves, “How do we get to the point where psychically we get somewhere else together? For better or worse we are sharing this planet. So how do we get beyond this point of the distraction of racism and into something bigger?” It’s not enough to simply exhibit the work of artists such as Tschabalala Self and Firelei Báez. We must apply the lessons we are gleaning from their work to make their muses and audiences feel as honored as the work itself.

1Firelei Báez, interview with author, July 1, 2022.

2Tschabalala Self, in Octavia Bürgel, “Inside the American Matrix of Artist Tschabalala Self,” High Snobiety, March 2021. Available online at https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/tschabalala-self-interview/ (accessed August 28, 2022).

3Aurielle Maria, interview with the author, July 9, 2021.

“Black to Black” also includes: “How to Collect Art” by Roxane Gay; “The Root of Black Joy: The Work of Bahamian Artist Gio Swaby” by Brooke C. Obie; “Leaps of Faith: A Conversation With Jordan Casteel and Calida Rawles”; “Commemorative Acts: Ladi’Sasha Jones” by Ladi’Sasha Jones; Kellie Romany: Many Bodies Corralled; and “Visual Abundance In The Work of Kezia Harrell” by Randa Jarrar