Jacquelynn Baas is a cultural historian, writer, curator, and director emeritus of the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Her books include Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art (2004), Smile of the Buddha: Eastern Philosophy and Western Art from Monet to Today (2005), and most recently Marcel Duchamp and the Art of Life (2019).

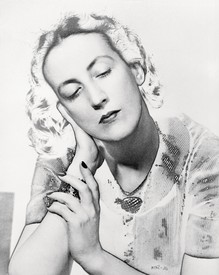

After one hundred radiant years of life, the flame that was Anna Halprin went dark on May 24, 2021. A choreographer, dancer, and influential teacher, Halprin radicalized dance, breathed life into performance art, and explored the potential of art for ecological and social reconciliation and healing.

The extraordinary combination of physical and intellectual energy that was Anna Halprin was the result of both her own innate abilities and the environment in which she grew up. Halprin attended elementary school in Winnetka, Illinois, home to the Winnetka Plan: a progressive, experience-based curriculum in the public schools, informed by John Dewey’s theories linking pedagogy with individual development and social reform. Dance was offered from the time Anna was in kindergarten, and by high school, dance was part of everything she did: “I was placed in ‘slow’ classes. . . . Now, they call it ‘motor learning’; I’m a motor learner, I learn through motor activities.”1 As a motor learner, Anna—who was also a natural teacher—excelled to such a degree that by the age of twelve she was leading classes in movement and improvisation for her friends and their mothers.

Dewey’s influence on Halprin’s artistic career continued in college: from 1938 to 1942, she studied at the University of Wisconsin–Madison with the legendary dance teacher and theoretician Margaret H’Doubler, whose teaching was based on knowledge of the capabilities of the human body. H’Doubler had studied at Columbia with Dewey, whose theory of “art as experience” was influential for many artists. For Dewey, the interaction of the body with its environment was key to making explicit the implicit aesthetic quality of everyday life.2 The implications for dance as a fundamental art form were not lost on H’Doubler or on her student. Halprin would later go on to apply Dewey’s theories regarding the importance of emotions within the art process.3 As her work developed, she would court occasions for physical and emotional tension, both between dancers and with the environment, to achieve new levels of equilibrium.

In 1946, Halprin and her husband, the Bauhaus-trained environmental designer Lawrence Halprin, moved to Northern California, a region that opened her up to new ways of seeing and working. She saw California as a promised land offering her the opportunity “to reassess and redefine dance in the same way that my husband Larry redefined landscape architecture.”4 Halprin’s new way of thinking about dance was based on her unconventional understanding of form: “Like [seeing] the stillness of the tree in relationship to the bird that just flew by . . . that’s form. That’s organizing the way you experience things. Form is not necessarily cause and effect, because there was no cause or effect, when I absorbed that bird moving. Perception is giving form to sensory experience.”5

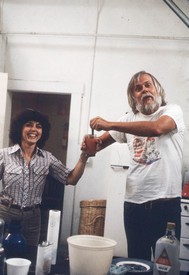

In 1953, Lawrence Halprin, working with theater designer Arch Lauterer, designed an outdoor wooden dance deck for Anna. Fifty feet below their house on Mount Tamalpais, Marin County, this small amphitheater built into the hillside was in effect an open-air studio that made it possible for Halprin to work in proximity to her children and to experience herself as part of nature. Informed by the interdisciplinary process of the Bauhaus, Halprin’s workshop concept approached creativity as group problem-solving by individuals who together generated work that none of them could have created alone. The dance deck became the site for Halprin’s groundbreaking San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop, which she established in 1955 (and later for the Tamalpa Institute, cofounded with her daughter Daria in 1978).

Despite its remote location in Kentfield, California, the Dancers’ Workshop had immense ramifications in the world of art and performance. John Cage and Merce Cunningham spent time with her there, and her students included Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, Meredith Monk, Robert Morris, and Yvonne Rainer, all of whom moved to New York and led the 1960s explosion of performance and interdisciplinary art. Halprin’s own work from the late 1950s and 1960s was prophetic of developments to come. Her collaborative improvisation Duet, for example—a 1958 performance that involved energetically moving while exchanging breath by “playing” opposite sides of the same harmonica—presaged the interactive performance art of Ulay and Marina Abramović in the 1970s. In 2015, Janine Antoni (who had traveled to California to study with Halprin) and Stephen Petronio collaborated on Swallow as a “visceral ritual of communication.”6

Avant-garde musicians including Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, and La Monte Young were part of Halprin’s workshop process. Young wrote many of his seminal Compositions 1960—instructions to be performed or imagined in open-ended ways—while working with her. After moving to New York, he became involved with the intermedia art enterprise Fluxus, whose impresario, George Maciunas, announced in an early prospectus for Fluxus Yearboxes that Halprin would contribute her Landscape score for a 45 Minute Environment (1962) to Fluxus 1.7 Landscape Score was indeed published in 1964 in Fluxus 1 (or in some versions of it—the contents varied slightly). According to Halprin, “We used to send scores back and forth, but at the time we weren’t calling them scores. . . . I called them ‘events.’ On the East Coast, they were calling them ‘happenings.’ . . . I remember setting up correspondence with Yoko Ono. She would send me events. One of them was a falling event, and I remember doing it in San Francisco, where every five minutes people would just let loose in the city—every five minutes fall, wherever you are.”8 Fluxus 1 also included the score for Young’s Trio for Strings, which had accompanied Halprin’s seminal Birds of America, choreographed and performed in 1960 by her Dancers’ Workshop.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Halprins organized a series of cross-disciplinary “Experiments in Environment” workshops that brought together dancers, architects, environmental designers, and artists in actions designed to foster environmental awareness and group creativity. The workshops took place in three distinct environments: the urban environment of San Francisco, the suburban environment of Kentfield, and the wildness of the Pacific Coast, at Sea Ranch (for which Lawrence had created the master plan). Participants engaged in a series of multisensory activities based on loosely structured open scores—collective building projects using driftwood, for example.9 Among the participants in the 1968 “Experiments in Environment” was architect and artist Chip Lord, who would go on to cofound the alternative-architecture-and-media collective Ant Farm (1968–78).

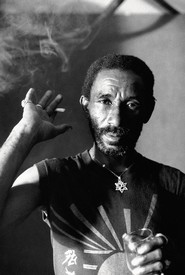

Halprin was also an innovator in artistic explorations of social and ecological realities. At a time of racial tension, she trained and then brought together Black performers from the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles with white performers from San Francisco in her Ceremony of Us (1968). The challenging situations Halprin created for her dancers were intended to “integrate emotional responses through an art process. . . . I wanted the dancer to be a whole, [socially aware] person.”10 She organized workshops with HIV-positive and cancer patients (she herself was a cancer survivor) and created group rocking-chair events with elderly people. Halprin’s annual community ritual on Mount Tamalpais, Planetary Dance, began in 1981 and continues to this day.

As she aged, Halprin explored themes of change and the body’s relationship with nature in performances that deployed the expressive power of her own naked body to powerful effect. Performing in 2002 with Eiko & Koma in the dance program Be With, Halprin became a “slow-moving traveler inching toward death,” according to one critic: “Dance is life, she suggests, as she recalls her prancing as a 5-year-old. ‘When I was 40, I danced for social justice and peace,’ she tells the audience and thrusts her arm up. . . . At 110, she says, ‘I will dance the way things really are.’ . . . In short, she reverts to the childlike prance with which she began. She repeats it, and then touches the floor (earth) with her palm.”11 Farewell Anna Halprin, still dancing.

1Anna Halprin, in Jacquelynn Baas, “Life as Art: Anna Halprin Interviewed by Jacquelynn Baas,” in Mary Jane Jacob and Baas, eds., Chicago Makes Modern: How Creative Minds Changed Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 242.

2See John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York: Minton, Balch, 1934), pp. 11–15.

3Ibid., pp. 15–17.

4Halprin, in Baas, “Life as Art,” p. 240.

5Ibid., p. 244.

6See Adrian Heathfield, ed., Ally: Janine Antoni, Anna Halprin, Stephen Petronio, (Philadelphia: Fabric Workshop and Museum; Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2017), pp. 95–111.

7See Baas, “Revolving Together Like Stars: The Art of Anna Halprin,” in ibid., p. 155.

8Baas, Chicago Makes Modern, p. 246.

9See Graham Foundation, “Experiments in Environment: The Halprin Workshops, 1966–1971,” 2014. Available online at http://grahamfoundation.org/public_exhibitions/5241-experiments-in-environment-the-halprin-workshops-1966-1971 (accessed June 21, 2021).

10Halprin, quoted in Janice Ross, Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), p. 267. Bracketed clarification: personal communication to Baas, April 10, 2016.

11Anna Kisselgoff, “Travel Companions on Life’s Inevitable Journey,” New York Times, January 31, 2002. Available online at http://eikoandkoma.org/sites/ek/images/ek_3563_pdf.pdf (accessed June 2021).