Connor Garel is a writer and editor from Toronto. He is the former Cannonbury Fellow at The Walrus and was previously an associate editor at HuffPost Canada. His writing on arts and culture has appeared in BuzzFeed, Canadian Art, and Vice.

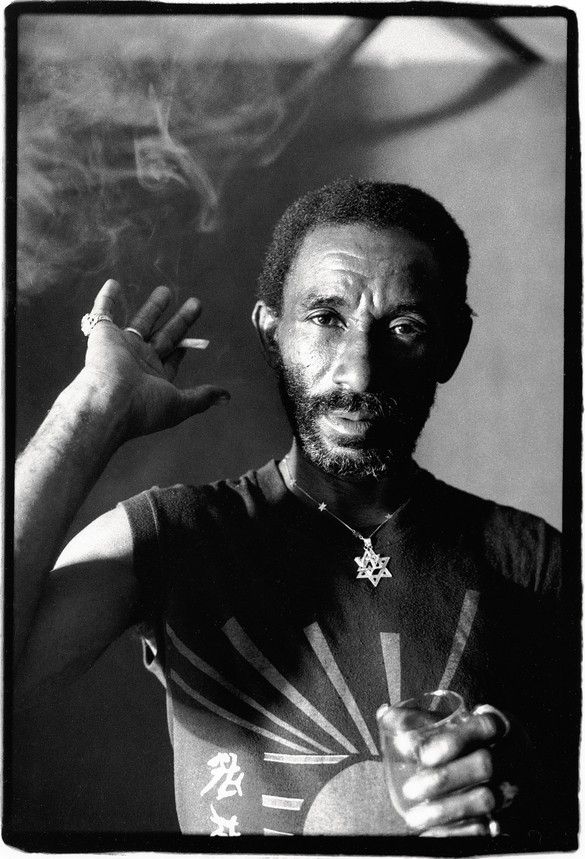

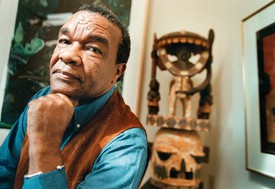

It probably started in Negril. It was the mid-1950s and Lee “Scratch” Perry was still in his early twenties, drifting about in Kendal and playing dominoes, which had suddenly, by the misfortune of his disenchantment, become redundant. He was beginning to hear news about the birth of a promising industry, a gleaming chance to circumvent the inheritance of his family’s rural poverty: in a bid to accommodate new tourism, Negril, a then underdeveloped part of western Jamaica, was getting some work done, and somebody had to be there to do that work.

So to Negril he went, to help build the first road into the resort town. “When I was working with the rock,” Perry said of his construction labor, “I picked up these sonic vibrations. . . . When you throw the rock, it sounds like when you hear the thunder roll.” Nature whispered many things. Tumbling boulders sounded to him like beating drums; violent winds were like crashing cymbals. It was this poetic ear that led Perry to revolutionize the way we think about sound and the possibilities of a song, and that made him one of the greatest artists, in any medium, of the last half century—one who forever changed the course of popular music worldwide.

By the time Perry got to Kingston, Jamaica’s capital, in the late ’50s, a whole circuit of mobile discos had cropped up to embrace the city’s working class, who had fallen hopelessly in love with the towers of bass-heavy speakers that pumped the dance-friendly riddims of ska, the ascendant musical form of the time. Perry quickly folded himself into the fray, working first as a janitor at Coxsone Dodd’s legendary Studio One, then ghostwriting and producing dozens of catchy songs there. But his relationships with the producers soon became acrimonious and the young engineer decided to form his own label, Upsetter Records. In 1968 he released his first major single, a loose and bubbling diss track called “People Funny Boy,” for which he ingeniously tucked the sound of a cooing baby into a muscular rhythm that is today credited both as the first reggae beat ever made and the first instance of sampling in recorded music. The song marked the inauguration of a new and pliant musical genre designed to carry sharp social commentary about a Kingston marred by political upheaval. Perry believed in confession, in music that could “make wrongs right”; reggae was the sound of the dispossessed, speaking truth to spiritual power.

Perry found music in the most unlikely places. That he sampled this odd bundle of noise in “People Funny Boy” nine years before Stevie Wonder’s “Isn’t She Lovely” opened with the cries of a newborn baby, and two decades before Timbaland placed his own gurgling baby sample on Aaliyah’s twitchy, lilting “Are You That Somebody” (which clearly inspired many of Destiny’s Child’s Writing’s on the Wall–era songs), is a testament to his clarity of vision. Perry anticipated the forms and moods of popular music before anyone else could get there. It was this cultural forecasting that attracted a young Bob Marley, who, desperately in need of a new sound, was offered the series of sparse and haunting tracks that became 1970’s Soul Rebels. (Perry also produced Marley’s “Keep on Moving,” “Duppy Conqueror,” and “Mr. Brown.”) “I gave Bob Marley reggae as a present,” Perry said, like Prometheus bringing fire to mankind. He played the prophet, Marley played the king, and, with the help of the Wailers, they all made some of reggae’s finest and most powerful work, cementing them as the international stars who would smuggle the music to the world beyond Jamaica.

Many if not most of us now live our lives among sounds drawn subtly or unsubtly from Perry’s cosmological palette.

A whole constellation of artists was enamored of Perry’s slow, loping beats. He worked with the Congos, Junior Murvin, Paul and Linda McCartney, the Clash, the Beastie Boys—Jean-Michel Basquiat, too, cited the producer as an influence. Perry looked askance at the trappings of social convention, occupying instead that fraught and exalted cavity between genius and madness. “The studio must be a living thing,” he would say. “The machine must be live and intelligent.” Most Kingston studios in the ’70s used an expansive sixteen-track setup, but Perry made do with a basic four-track Teac recorder. The reggae historian Lloyd Bradley has said that Perry took musical ideas “way past the point at which logic would tell most people to stop,” which seems perfectly true: there were stories of him burying master tapes in his garden, then dousing them with whiskey, blood, and urine; of blowing weed smoke over recording equipment; of mic-ing a palm tree to capture the “living African heartbeat.” Keith Richards once described him as “the Salvador Dalí of music.” “The world is his instrument,” Richards said. “You just have to listen.”

Many if not most of us now live our lives among sounds drawn subtly or unsubtly from Perry’s cosmological palette. It was Perry whose pioneering of dub music hammered down the foundations of contemporary electronic music. He’d take a reggae song and strip it down to its riddim only to rebuild it, slipping it to a newer, shinier outfit. He’d stretch a sweet voice into a quivering, spectral moan; a drumline would stutter and get woozy, as if it were stoned; an existing song became, somehow, a new one, both reenergized and distinct, as though it had sprung from the depths of a stem cell. He revised the role of a studio engineer and remade it in his own image, which was the image of an auteur.

Popular culture is, of course, Black culture, and the world has run up a historical deficit it can never stabilize. The writer Sharine Taylor has noted how Jamaica’s soundscapes are so often adopted by non-Caribbean artists that its originators seem constantly at risk of being painted over. So what does it mean that we’re so deeply indebted to a single man, this freewheeling multiverse who made so much beauty? If you’ve ever pressed play on a song by Arca, or FKA Twigs, or Flying Lotus, or indeed have spent time at some rave improvised beneath a city highway, then you’re cashing in on the seeds Perry planted. From house, jungle, and garage to dubstep, rock, and hip-hop, the immortal giant haunts the canon. Perhaps he hasn’t really died, present as he is all around us, fragments of that interstellar legacy floating about in all that we listen to—shimmering in all the delays, the echoes, the reverbs, the sounds that bore into our joints and release our bodies into motion.